Do you ever see those ‘Top 10 habits of successful people' style articles? The ones where we're encouraged to instill in ourselves an entrepreneurial spirit by digesting the same breakfast as Elon Musk or exercising to the same schedule as Jeff Bezos? Well, one thing these articles all seem to have in common is the advice that we should definitely be getting up earlier. An early riser gets a head start on the competition and all that.

So is that where I've been going wrong? Have I been too fond of a lie in all this time? Would those two extra hours a day be the ones to turn mediocrity into fortune? I can't shake the question, so I thought I'd see what I could find on the shelves.

First, a poem.

When he is a little chap, / We call him Nap. / When he somewhat older grows, / We call him Doze. / When his age by hours we number, / We call him Slumber.

Sleep by John B. Tabb (1894)

When you stop and think about it, sleep is really rather an odd way of spending time. As George Carlin once observed:

People say, 'I'm going to sleep now,' as if it were nothing. But it's really a bizarre activity. 'For the next several hours, while the sun is gone, I'm going to become unconscious, temporarily losing command over everything I know and understand. When the sun returns, I will resume my life.'

But what are we to make of this absurd state we spend a third of our lives in? Are we to give ourselves over to this temporary loss of consciousness or is the resumption of our life, as the self help articles suggest, not of the utmost urgency?

Plato tended towards the 'lets get this over with and crack on with life' school of thought, writing in Laws, his last and longest dialogue that:

Asleep, man is useless, he may as well be dead... [it's] a disgrace and unworthy of a gentleman… if he devotes the whole of any night to sleep (Laws 297)

I think what he's getting at, in a rather heavy handed fashion if I can permit myself a momentary critique of the great man, is that we're giving up too much when we sleep. It's the lost time, the lost life, that is the tragedy. Edgar Allan Poe agreed, reportedly once exclaiming:

Sleep, those little slices of death — how I loathe them.

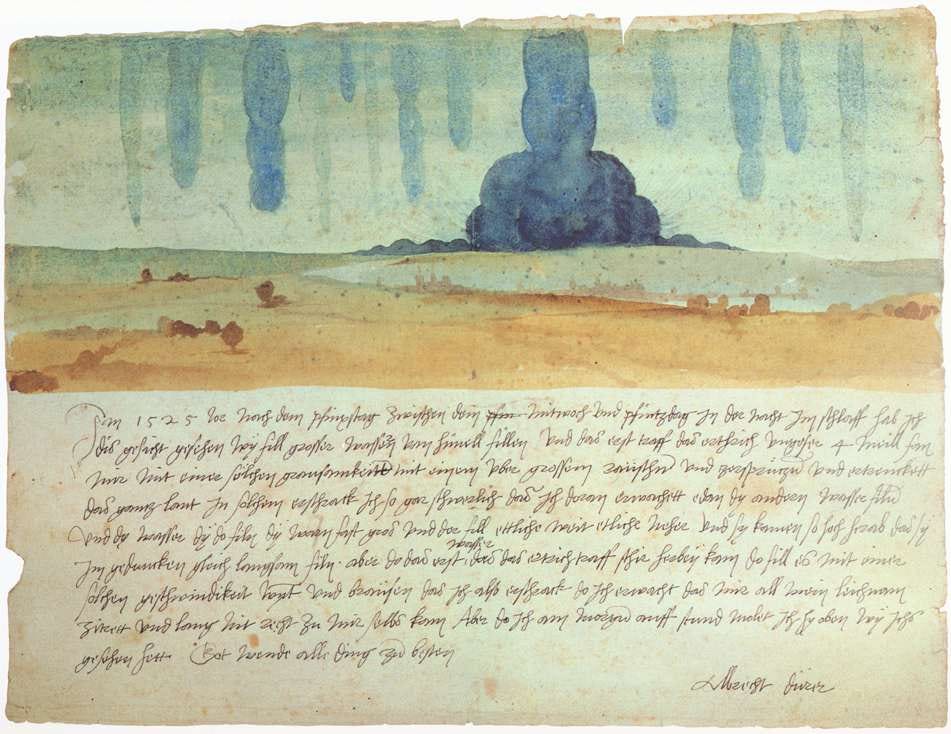

Albrecht Dürer, Dream Vision, 1525

Is that the answer, then? Eschew sleep as much as we can in favour of getting on with the business of living? Well there's a few great minds on the get-up-and-get-started-with-the-day side of the argument, including:

Thomas Edison, who claimed he never slept for more than 4 hours a night

Nikola Tesla, who capped his nighttime sleep at just 2 hours before topping up with power naps through the day

Leonardo Da Vinci, who forewent the idea of 'bedtime' entirely in favour of short, 20 minute naps every four hours

Pretty convincing. But if your soul is of the sleepier variety, and you rarely find yourself anxious to continue your productive endeavours into the night, you might be feeling a little troubled by all this. Don't worry, the shut-your-eyes-and-ignore-the-world-for-as-long-as-possible side of the debate finds exponents in:

Albert Einstein, who is said to have slept for 10 hours every night

And the father of modern Western thought himself, Rene Descartes, who took as many as 12 hours a night and often worked from his bed

So it's still possible to be productive and enjoy your slumber. And isn't it the case that some of our most productive thinking is undertaken in the state of sleep?

Leading the way on having your cake and eating it is Lord Vishnu who, in Hindu mythology, is often depicted in a state of yoga nidra (cosmic sleep) on the serpent Ananta. During this time, he dreams the entire universe into existence, with not a power nap in sight.

But what of us mere mortals? Sleep, for us, can still offer brief moments of creative inspiration. There's a lot to be said, in particular, for the semi-lucid state in-between sleep and wake. Salvador Dali, that chaser of dreams, certainly thought so, outlining in his 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship for aspiring painters his technique for one-second micro-naps, which involved holding a set of keys above a plate which would inevitably fall as soon as sleep struck, making possible the grasping of whichever vision was making its way across the consciousness.

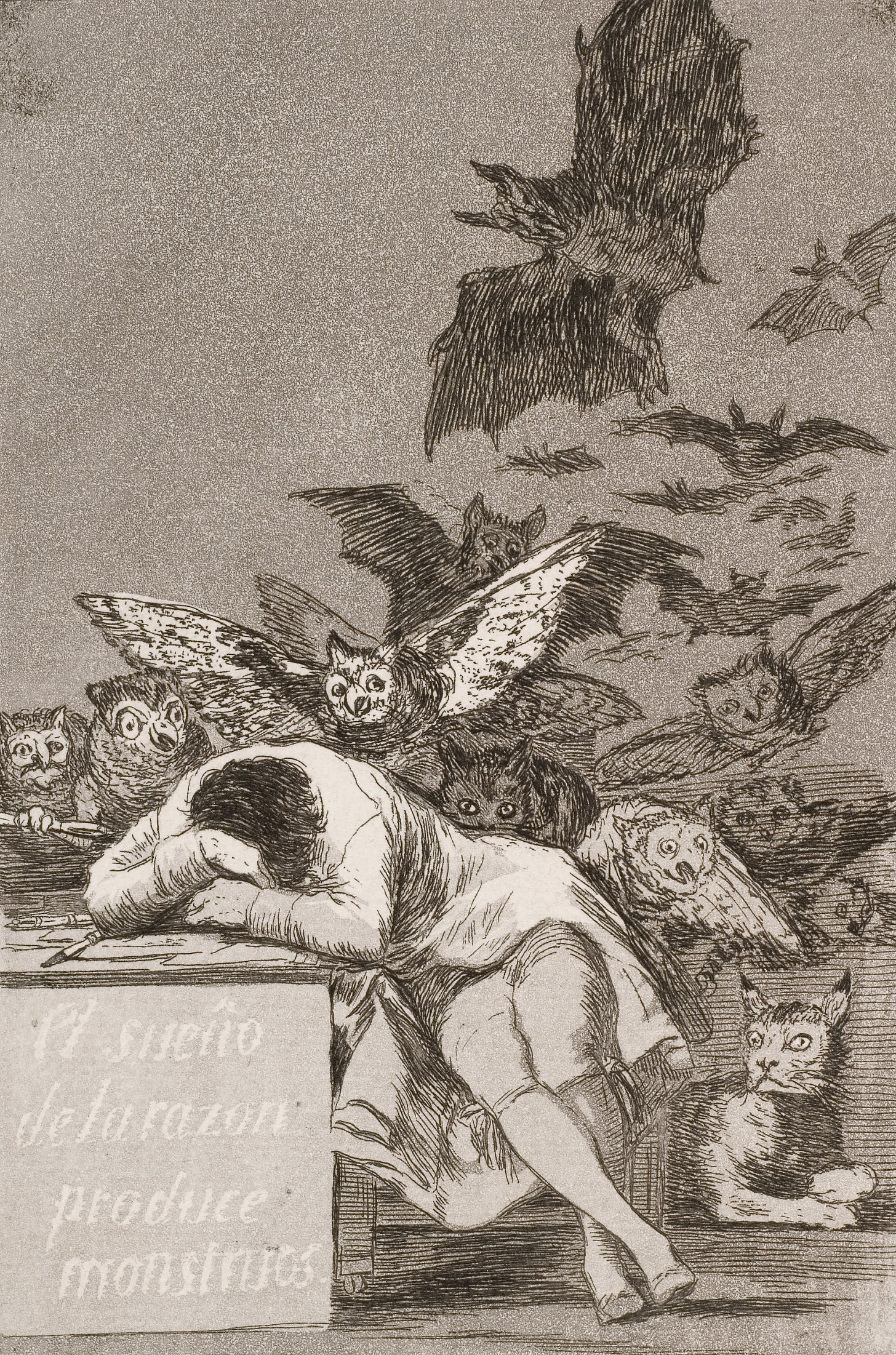

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, Francisco de Goya, 1799

But sometimes even the best of us need a little support. Here's the narrator of Marcel Proust 's À la recherche du temps perdu (1913), somewhere in rural France, sometime in the late 19th century, struggling in the task of nodding off until recieving the longed-for kiss goodnight from his mother.

My sole consolation when I went upstairs for the night was that Mamma would come in and kiss me after I was in bed. But this good night lasted for so short a time: she went down again so soon that the moment in which I heard her climb the stairs, and then caught the sound of her garden dress of blue muslin, from which hung little tassels of plaited straw, rustling along the double-doored corridor, was for me a moment of the keenest sorrow. So much did I love that good night that I reached the stage of hoping that it would come as late as possible, so as to prolong the time of respite during which Mamma would not yet have appeared. Sometimes when, after kissing me, she opened the door to go, I longed to call her back, to say to her "Kiss me just once again," but I knew that then she would at once look displeased, for the concession which she made to my wretchedness and agitation in coming up to me with this kiss of peace always annoyed my father, who thought such ceremonies absurd, and she would have liked to try to induce me to outgrow the need, the custom of having her there at all, which was a very different thing from letting the custom grow up of my asking her for an additional kiss when she was already crossing the threshold. And to see her look displeased destroyed all the sense of tranquillity she had brought me a moment before, when she bent her loving face down over my bed, and held it out to me like a Host, for an act of Communion in which my lips might drink deeply the sense of her real presence, and with it the power to sleep.

It's a power that came slightly easier to Endymion, the handsome young shepherd of Greek mythology. So beautiful was this mortal, especially during sleep, that Titan goddess Selene asked Zeus to leave him in that state forever, securing for all time his youth and his beauty.

But if eternal sleep secures eternal youth and beauty, what of its opposite? What happens if we are deprived of our sleep? Allan Rechtschaffen's famous 1995 sleep deprivation experiments used rats to try to answer that question, reporting that:

The deprived rats show a reliable syndrome that includes temperature changes (which vary with the sleep stages that are lost); heat seeking behavior; increased food intake; weight loss; increased metabolic rate; increased plasma norepinephrine; decreased plasma thyroxine; an increased triiodothyronine-thyroxine ratio; and an increase of an enzyme which mediates thermogenesis by brown adipose tissue... The sleep deprived rats also show stereotypic ulcerative and hyperkeratotic lesions localized to the tail and plantar surfaces of the paws, and they die within a matter of weeks.

Now, if you're of the sensibility that means you're currently sick with rage on behalf of these innocent creatures, I'd advise you look away at this point. What comes next is a nightmarish description of Victorian Britain by historian Roger Ekirch in At Day's Close: Night in Times Past. What it teaches us about sleep, I'm not sure, but what it teaches us about human nature is so harrowing that I felt compelled to wedge it in here somewhere:

Labour discipline in a Lancashire cotton mill during the 1830s entailed parading the effigy of a ghost across the shop floor at night to deter child workers from sleeping.

You read that right, reader. It brings me no pleasure at all to be for you the conduit of the knowledge that somewhere in our planet's history our fellow man was maximising the economic output of children by keeping them awake at night with a hand made toy ghost.

I don't know about you, but I'm becoming more and more convinced of the benefits of escaping into a dream world of my own imagination, a gift of escape that wasn't lost on Borges:

If sleep is truce, as it is sometimes said, / a pure time for the mind to rest and heal, / why, when they suddenly wake you, do you feel / that they have stolen everything you had?

Why is it so sad to be awake at dawn? / It strips us of a gift so strange, so deep, / it can be remembered only in half-sleep, / moments of drowsiness that gild and adorn.

The waking mind with dreams, which may well be / but broken images of the night’s treasure, / a timeless world that has no name or measure / and breaks up in the mirrors of the day.

Who will you be tonight, in the dark thrall / of sleep, when you have slipped across its wall?

Sleep by Jorge Luis Borges (1923)

Legend of St Francis: Dream of the Palace, Giotto, 1297 – 1299

In Portugal, they have a word for someone who lives in their dreams. Translating literally as 'cloud walker,' Nefelibata is a term that could readily be applied to that nation's greatest poet, Fernando Pessoa:

I’ve dreamed a lot. I’m tired now from dreaming but not tired of dreaming. No one tires of dreaming, because to dream is to forget, and forgetting does not weigh on us, it is a dreamless sleep throughout which we remain awake. In dreams I have achieved everything.

The Book of Disquiet (1982)

The Artist’s Dream, George H. Comegys, 1840

Who will you be tonight? In dreams I have achieved everything. What a gift these poets suggest sleep can be! For Elizabeth Barrett Browning, it's the greatest gift there is:

Of all the thoughts of God that are / Borne inward unto souls afar, / Along the Psalmist's music deep, / Now tell me if that any is, / For gift or grace, surpassing this,— / "He giveth his beloved, sleep!

The Sleep by Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1844)

For Shakespeare, it's the gift of relief from the day:

Sleep that knits up the ravell'd sleeve of care, / The death of each day's life, sore labour's bath, / Balm of hurt minds, great nature's second course, / Chief nourisher in life's feast.

Macbeth (1606)

For Hemingway, it's the gift of relief from life:

I love sleep. My life has the tendency to fall apart when I'm awake, you know?

And, finally, for Emil Cioran (who I wrote about last week), it's the gift of relief from the greatest tormentor of all: ourselves.

If we could sleep twenty-four hours a day, we would soon return to the primordial slime, the beatitude of that perfect torpor before Genesis-the dream of every consciousness sick of itself.

The Trouble with Being Born (1973)

Good enough for me. I'm turning back over for another hour.

It was a amazing to hear what all these great thinkers think about sleep! Have you looked into the concept of lucid dreaming? I've heard some people have used this state to practice a skill, solve a problem, etc. I've always wanted to commit to trying it but it seems quite difficult to induce!

Thank you for this very entertaining & informative essay. You display such an engaging mastery of interdisciplinary framing devices in your writing. Your conclusion thankfully relieves my guilt in sleeping 😴 in tomorrow on my vacation day!