Issue #13: Are We at the Dawn of a New Age of Mythology?

Vico, Nussbaum and Ancient Chinese Art

Since I was a boy, I have felt at home in the worlds of language, music, stories, and poetry. Mathematics and the sciences, with their strict logic and cold precision, have always felt like foreign ground. By the standards of the educational and economic establishment, this makes me second-rate. My skills, my way of knowing the world, are considered secondary—an ornament rather than an engine in the grand machinery of human progress.

It was with great pleasure, then, that my reading this week took me to the work of a man who finds in our oldest stories the hidden logic that shapes human culture. Giambattista Vico does not ask whether myths are true—he asks why we create them, why we need them, and why, even in an age of progress and reason, we can never quite escape them.

But that's not all I have for you most valued of readers as we begin this miserable February. There's also a framework, courtesy of Martha Nussbaum, to help us measure the extent to which we're living The Good Life. You'll note the absence of any personal reflections from that section.

In the issue:

Giambattista Vico on society's ‘inevitable’ return to mythology #literature

Martha Nussbaum offers a framework to measure human flourishing #philosophy

Seneca judges you for showing off your bookshelf #education

Poetic murmurings from the Middle Ages #linguistics

A different way to conceptualise humanity’s relationship with nature #art

As always, something to think about this week

Are We at the Dawn of a New Age of Mythology? Giambattista Vico on Myth and Memory

Whilst Enlightenment thinkers were convinced that history was a steady march towards progress, there was one man, overlooked in his time, who saw something different.

Giambattista Vico, a Neapolitan philosopher writing in the early 18th century, rejected the prevailing belief that reason and progress would lead humanity ever upward. Instead, he argued that history moved in cycles, not straight lines, and that every great civilisation, no matter how advanced, would eventually collapse under the weight of its own sophistication.

Where Enlightenment thinkers saw a future of rational governance, scientific mastery, and endless improvement, Vico saw a more unsettling pattern. Societies, he argued, begin in a state of myth and poetry, where traditions and shared beliefs create unity. Over time, they develop laws, institutions, and systems of knowledge that bring order and progress. But as these structures grow more abstract, more detached from real life and real human concerns, they become brittle and unresponsive. Bureaucracy multiplies, language becomes jargon, politics devolves into endless debate, laws become so convoluted they are meaningless, culture fragments into competing ideologies, and society drifts into what he called the "barbarism of reflection"—a state of paralysis, cynicism, and decay. The result is cynicism, alienation, and ultimately, the return of chaos.

Ignored in his lifetime, Vico’s insights have become eerily relevant, his warnings feeling less like a relic of the past and more like a prophecy unfolding before our eyes.

If you want to trace the evolution of a culture, to unpack the deep logic of its values and institutions, you could do a lot worse than start with its myths. Which is exactly what Vico does.

To Vico, myth was not an arbitrary collection of stories, not a set of primitive superstitions waiting to be outgrown, but a vital and necessary mechanism through which human societies understood themselves.

Vico’s great work, The New Science, proposed that history followed a cyclical pattern, one in which societies moved through distinct stages of development. At the dawn of civilisation, in what he called the “Age of Gods,” people lived in awe of the natural world, crafting myths as a way of making sense of forces they could not control.

This was an era of thunderbolts and prophecies, of sacred law handed down from above. Think Zeus atop Olympus, or the Old Testament God thundering commandments from a mountaintop. These were not just stories; they were the organising principles of entire civilisations.

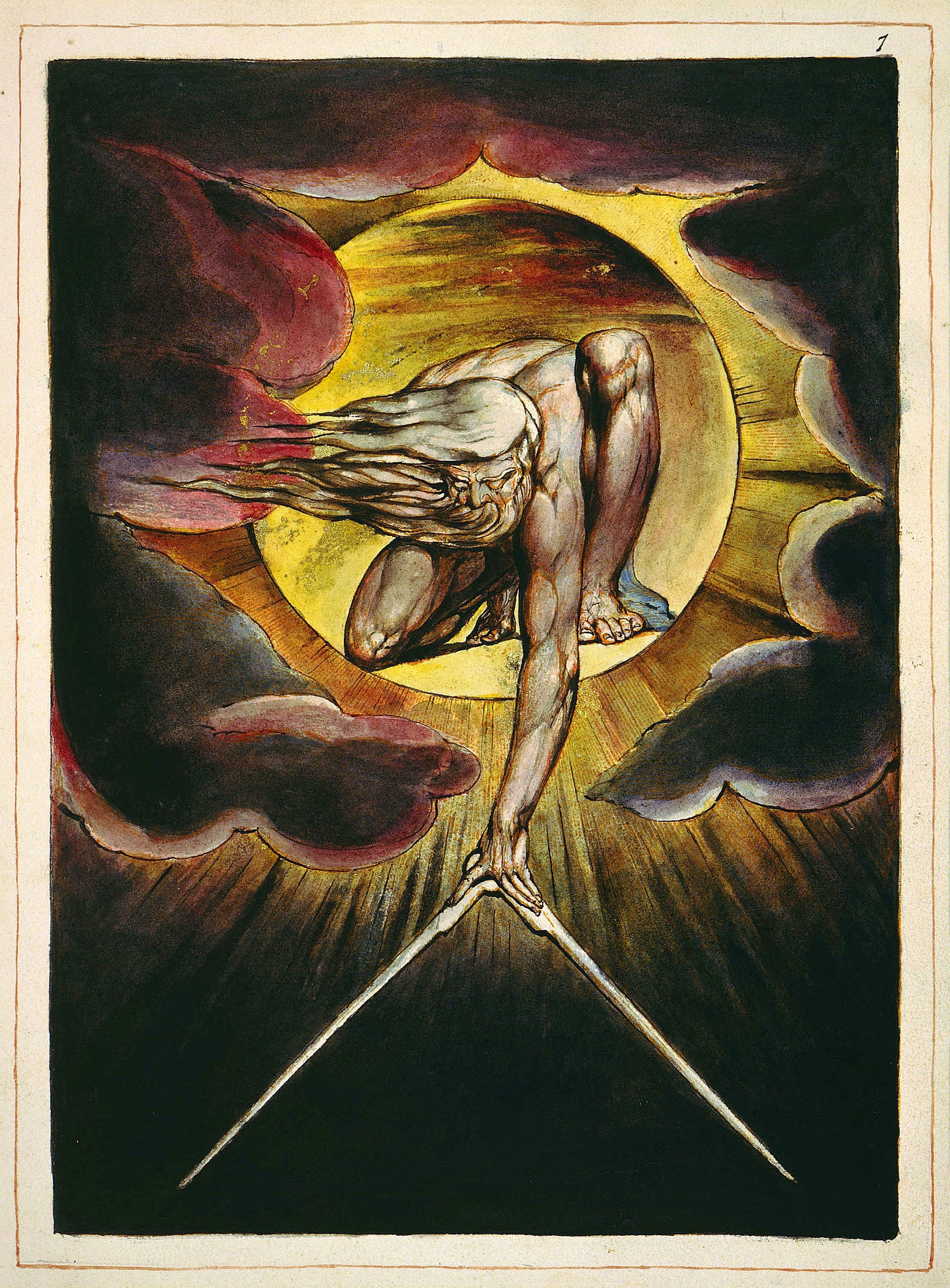

William Blake, The Ancient of Days, 1794

For Vico, the origins of these myths lay in fear. The first humans—isolated, brutish, barely conscious of themselves as a species—lived in a world that must have seemed vast and terrifying. The sky cracked open with thunder, the earth trembled with unseen power, and in their ignorance, they assigned these forces human-like intentions.

As Vico put it, they "pictured the sky to themselves as a great animated body," calling it Jove, the first and greatest of gods. This projection, the impulse to ascribe human traits to non-human things, was not a failure of reason but an instinctual response, a necessary fiction that allowed early societies to impose some kind of order on a chaotic and unpredictable world.

Here, Vico prefigures later thinkers like Ludwig Feuerbach, who would argue that gods are not discovered but invented, shaped from human fears and desires. But for Vico, mythology was not simply a mistake to be corrected. It was the foundation of civilisation itself. Fear of divine retribution, he claimed, was the first step towards law and social order.

"Providence gave to savage and brutish men the impulse toward humanity and the creation of cities," he wrote, by awakening in them "a confused sense of divinity which in their ignorance they ascribed to beings unsuited for it." The gods of myth, then, were not arbitrary superstitions; they were the first regulators of human behaviour, the earliest form of law.

With time, the myths evolved. Human figures replaced divine ones, and so began the “Age of Heroes.” Here, aristocratic warrior-kings took centre stage, ruling through a mix of brute strength and rigid hierarchy. The gods still loomed large, but now they worked through men—Achilles, Odysseus, Romulus. These figures, Vico argued, were not purely fictional. They were expressions of real historical developments, stylised through the lens of collective memory. Myth, for Vico, was always a translation of reality, distorted but not detached.

Then came the “Age of Men.” Rationality crept in. Law replaced custom, democracy pushed aside the warrior-elite, and societies began to see themselves in legal codes rather than heroic epics. Mythology faded into literature. The supernatural was stripped away, leaving only the remnants of old stories fossilised in poetry and drama. What had once been a living, breathing cultural force was now an artefact, a relic to be studied rather than believed.

But here’s where Vico’s theory becomes more than just another historical framework. The cycle does not simply progress in a straight line. It repeats. Societies, having reached their peak of reason, do not stay there indefinitely. Instead, they decline into what Vico called the “Barbarism of Reflection,” a period in which hyper-rationality leads to scepticism, cynicism, and eventually, collapse.

When civilisations collapse, they do not simply disappear—they begin again, reverting to myth, to poetry, to the primal stories that first gave them coherence.

This belief in historical cycles (ricorsi) was largely influenced by his interpretation of the Middle Ages. Vico saw this period as a resurgence of an earlier heroic age—a new form of barbarism. Some of the most striking sections of The New Science explore the parallels between medieval society and the mythic past, highlighting the cruelty, rigidity, and narrow worldview that both eras shared. As a devout Catholic, Vico made the bold claim that medieval rulers, with their divine titles and sacred authority, were reenacting the self-deification of ancient Greek heroes—both being products of similar social conditions recurring throughout history.

One of the great anti-enlightenment thinkers, it's not difficult to see why Vico struggled for recognition in his time, but in the 19th and 20th centuries, as scholars began to take mythology seriously again—as thinkers like Nietzsche, Freud, and Lévi-Strauss grappled with the power of ancient narratives—Vico started to look, and continues to look, remarkably prescient.

What Does Wellbeing Really Mean? Martha Nussbaum's Framework for Human Flourishing

We have annual wellbeing days at my place of work. It's a day where we can finish our productive endeavours at lunchtime on the condition that we sign up to various activities designed to improve our wellbeing. Such activities have in the past included pottery, yoga, escape rooms, team building games, vegan cookery workshops and zumba classes.

Now, I'm not one to complain about an early finish, and I very much enjoyed the 'quiet reading space' I signed up to last year, but it strikes me that, as a culture, we could really do with sharpening up our definition of 'wellbeing,' given that it's what we're all striving for in one way or another.

One interesting approach comes from Martha Nussbaum who, in Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach (2000) sought to set out a view of wellbeing that would transcend cultural and religious boundaries.

She takes Amartya Sen's distinction between functionings and capabilities as a starting point. Functionings, in this view, refer to the actual things a person manages to do or be in life. I might be a moderately good amateur tennis player and do a serviceable ragu, for example.

Capabilities, on the other hand, refer to the real opportunities or freedoms a person has to achieve the functionings they value. Capabilities are about what is possible rather than what is actually achieved. My ability to function as an amateur tennis player (I’m really overstating my talents now) relies on my freedom to access the necessary courts and equipment, whilst my ragu has been the result of years of experimentation in a kitchen of my own, with ingredients and utensils bought with money that I've been free to earn etc. etc.

But capabilities are not necessarily neutral. The question arises of what it is we should be capable of doing, because surely we need to draw up some boundaries somewhere? I might be capable of eating my body weight in digestive biscuits but it doesn't strike me as a particularly good measure of my quality of life.

One of Nussbaum's main departures from Sen's work, then, is in her spelling out of exactly what our necessary capabilities should be and her suspiciously round-figured list of ten can serve as a useful framework for evaluating wellbeing, regardless of divergent cultural dimensions at a local level.

Life – our capability to live to an adequate age.

Bodily Health – our capability to live a healthy life, including adequate shelter, reproductive health and nourishment.

Bodily Integrity – our capability to move freely, be safe from violence, and make decisions about our own bodies.

Senses, Imagination and Thought – our capability to think, imagine, create, informed by a satisfactory education.

Emotions – our capability to form attachments to things outside of ourselves. Empathy, love, grief.

Practical Reason – our capability to make our own decisions regarding the life we want to live and to critically reflect on it.

Affiliation - our capability to live in harmony with others, form social relationships, and be treated with dignity and respect.

Other Species - our capability to live in relation to, and show concern for, the environment and other living species.

Play - our capability to enjoy recreation, leisure, and play.

Control over One’s Environment - our capability to participate effectively in political life and to own our own property.

That'll just about cover our universal pursuit of human functioning. We're striving, says Nussbaum, to be healthy and free. Free from violence, free to think, free to live in harmony with the world and the people in it, free to construct our own existence rather than having it shaped by others.

I can't say I've read the text cover to cover, but I'm fairly confident that compulsory Zumba classes aren't a part of the framework.

Extract of the week #education

I'm a little tense at the minute. We've just moved to a new place where bookshelf space is limited, the small hill of books I call my own still tucked away in boxes. Chief amongst my current projects, then, is finding a few good walls upon which to display all of my fine taste and learning and intellect. Seneca sees me and disapproves…

‘Outlay upon studies, best of all outlays, is reasonable so long only as it is kept within certain limits. What is the use of books and libraries innumerable, if scarce in a lifetime the master reads the titles? A student is burdened by a crowd of authors, not instructed; and it is far better to devote yourself to a few, than to lose your way among a multitude.

Forty thousand books were burnt at Alexandria. I leave others to praise this splendid monument of royal opulence, as for example Livy, who regards it as 'a noble work of royal taste and royal thoughtfulness.' It was not taste, it was not thoughtfulness, it was learned extravagance—nay not even learned, for they had bought their books for the sake of show, not for the sake of learning—just as with many, who are ignorant even of the lowest branches of learning, books are not instruments of study, but ornaments of dining-rooms. Procure then as many books as will suffice for use; but not a single one for show. You will replay: 'Outlay on such objects is preferable to extravagance on plate or paintings.' Excess in all directions is bad. Why should you excuse a man who wishes to possess book-presses inlaid with arbor-vitae wood or ivory; who gathers together masses of authors either unknown or discredited; who yawns among his thousands of books; and who derives his chief delight from their edges and their tickets?

You will find then in the libraries of the most arrant idlers all that orators or historians have written—book-cases built up as high as the ceiling. Nowadays a library takes rank with a bathroom as a necessary ornament of a house. I could forgive such ideas, if they were due to extravagant desire for learning. As it is, these productions of men whose genius we revere, paid for at a high price, with their portraits ranged in line above them, are got together to adorn and beautify a wall"

Translated in Clark, The Care of Books, 1901

Image of the Week #linguistics

A starling murmuration in the sky above Rome, Italy. (Image: Søren Solkær)

The word "murmuration" originates from the Latin murmuratio, meaning "murmuring" or "low, continuous sound," derived from murmur. It captures the soft, whispering noise of thousands of starling wings as they move in perfect synchrony. However, its use to describe the birds’ mesmerising aerial displays reflects an old linguistic practice in English: the "nouning" of collective animal behaviours or traits. This tradition, popularised during the Middle Ages, is most famously recorded in The Book of Saint Albans (1486), which lists poetic "terms of venery" like a "murder" of crows or a "charm" of finches. Murmuration, with its rippling, rhythmic sound, perfectly evokes the starlings’ swirling, shape-shifting formations—a fusion of language and nature.

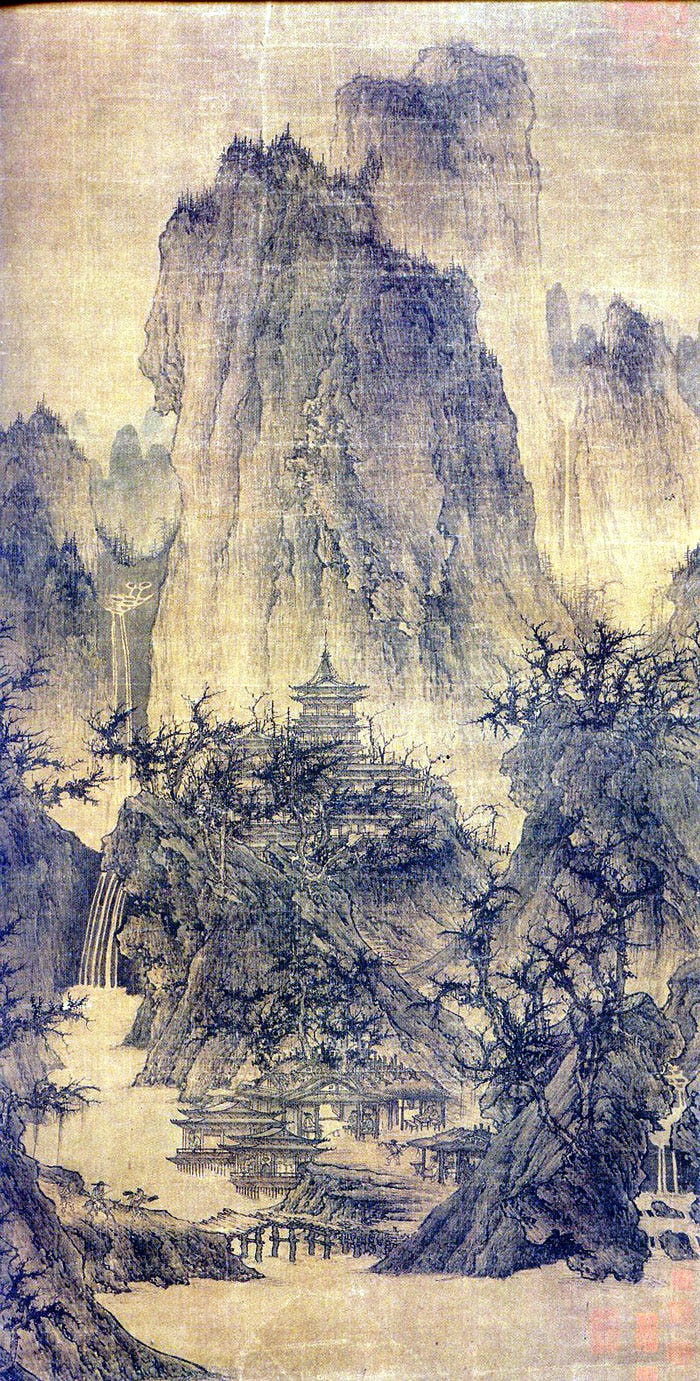

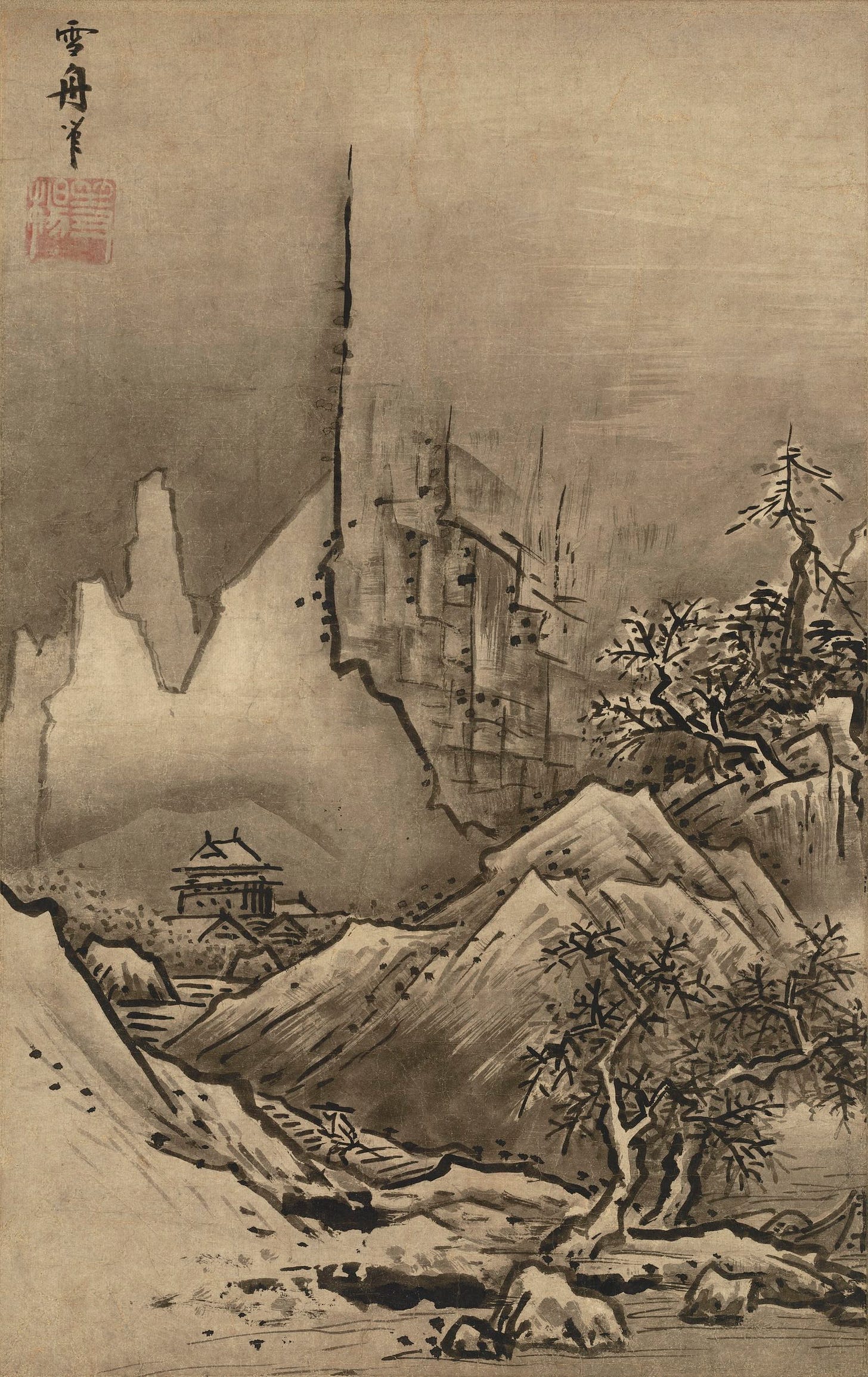

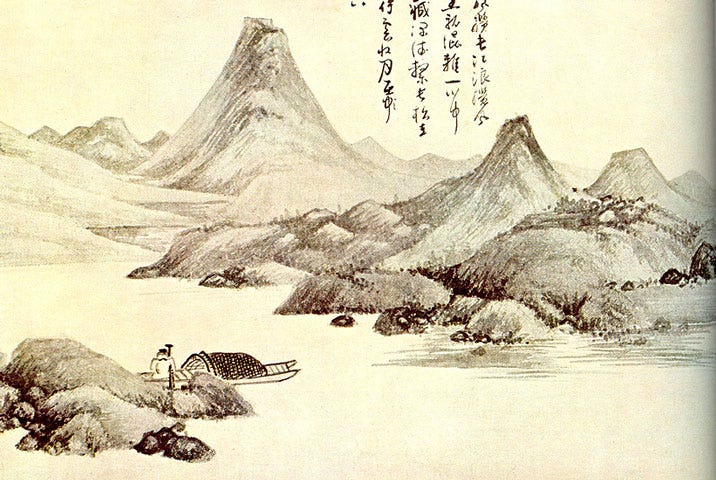

The Collection | Nature in Chinese Painting #art

Western art - traditionally and with many exceptions - has often depicted the natural world in the form of awe-inspiring, almost theatrical landscape. Think Caspar David Friedrich as the quintessential example. Nature might be idealised, romanticised, or even tamed, but it is often treated as "other" rather than an integral part of existence.

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich, 1818

Not so much in the Eastern tradition. Taoist beliefs emphasise that humans are an integral part of nature, not separate from or superior to it. We emerge from nature and are as such a part of nature. We don't exist 'on' or 'in' the natural world any more than an apple exists 'on' or 'in' an apple tree.

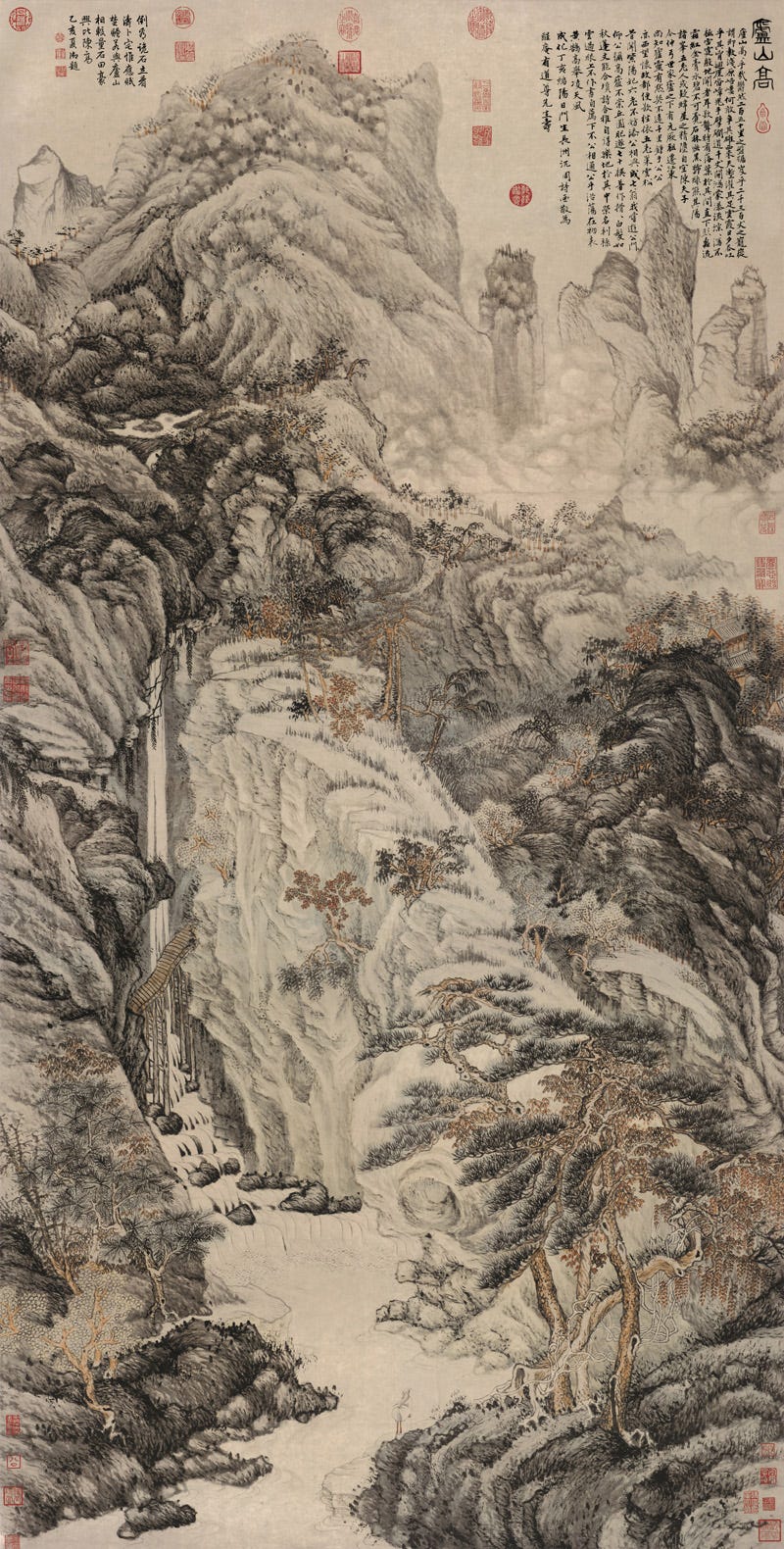

These beliefs are beautifully reflected in Chinese landscape painting, where nature takes centre stage and human presence is subtle. The following examples illustrate humanity’s small and humble place within the vast cosmos. While human figures or traces of human influence are present in each painting, they often blend seamlessly into the landscape, requiring careful observation to notice. A sort of Where's Waldo for the culturally and artistically curious.

Travellers Among Mountains and Streams by Fan Kuan (c. 1030)

A Solitary Temple amid Clearing Peaks by Li Cheng (c. 960)

Winter Landscape by Sesshū Tōyō (1470)

Fisherman, Wu Zhen (c.1341)

Lofty Mount Lu by Shen Zhou (1467)

The Examined Life

When we talk about the ingredients for a good life, we talk a lot about freedom. But is freedom meaningful if people lack the basic capabilities to make use of it? Should governments be responsible for ensuring that all citizens have the capabilities to live a meaningful life? And, if so, are there certain capabilities that are universally necessary for human well-being?

As always, I hope you've gathered a few book recommendations, if nothing else, from the issue this week. Here's where you can read further if anything inspired you to do so:

Giambattista, V. (1725). Principi di Scienza Nuova (The New Science)

Nussbaum, M. (2011). Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach

Clark, J.W. (1901) The Care of Books: An essay on the development of libraries and their fittings, from the earliest times to the end of the eighteenth century

Wucius Wong, W. (1970) Tao of Chinese Landscape Painting: Principles and Methods

And if you're minded to do so, sharing the post will help me to connect with new readers. I’m incredibly grateful!

Have a beautiful week!

Thanks for introducing Vico's cycle of gods to heroes to humans to new barbarism. A powerful lense for looking at our current situation. I have found Joseph Campbell's writing about the importance and meaning of our universal myths to be equally clarifying.

Just a lovely way to start this Sunday - thank you for such a gorgeous post! By the way - a charm of finches? As you say what a beautiful way to fuse language and nature.