According to Ovid, 'when there is plenty of wine, sorrow and worry take wing.' This week feels like a good week to put that theory to the test.

Perspective One: Wine as a source of inspiration

'Quickly, bring me a beaker of wine, so that I may wet my mind and say something clever.'

Aristophanes

Since it was first made, we believe around 6,000 to 7,000 BCE in what is now modern-day Georgia, wine, Shakespeare's provoker of ‘nose-painting, sleep and urine,’ (Macbeth, 1606) has been loosening tongues and inspiring creativity. Many a writer and thinker have spoken of how the relaxation it affords can open the gate to the vast potential of the mind.

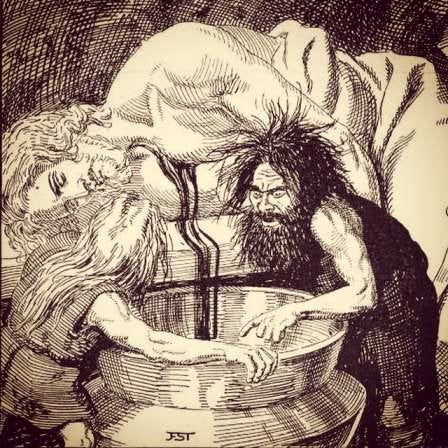

In Norse mythology, there's a story that points towards the link between wine and inspiration. After the Aesir-Vanir War, the gods chose to seal the peace, in charming fashion, by spitting into a huge vat. From this vat they created Kvasir, the wisest being who ever lived, for whom there was no question too complex.

One day, two dwarves by the names of Fjalar and Galar invited Kvasir to their home but, instead of granting the promised hospitality, killed him and drained his blood. The dwarves used his blood to brew mead, a honey based wine that carried in its essence all of Kvasir’s wisdom. They called it Óðrœrir, translating literally as ‘stirrer of inspiration.’ Anyone who drank Óðrœrir, sometimes called the ‘mead of poetry,’ would immediately become a poet or scholar, able to recite any information and solve any question.

Illustration by Franz Stassen (1869-1949)

Anyone who has ever woken up with a headache, cringing about some of the ‘insights’ they were sharing the night before, can appreciate the source material for this story. I imagine Baudelaire to be guilty of the above, although I'm sure his drunken philosophising was of more value than most. Here's an extract from his poem 'The Soul of Wine (1869),' in which he speaks, from the perspective of the wine itself, of its creativity-enhancing properties:

‘I shall light up the eyes of your enraptured wife, / And give back to your son his strength and his color; / I shall be for that frail athlete of life / The oil that hardens a wrestler's muscles

[...]

I shall descend in you / So that from our love there will be born poetry, / Which will spring up toward God like a rare flower!’

Pablo Neruda, too, could be found turning to the bottle for inspiration. Here's an extract from his Ode to Wine (1954):

‘Wine / stirs the spring, happiness / bursts through the earth like a plant, / walls crumble, / and rocky cliffs, / chasms close, / as song is born.’

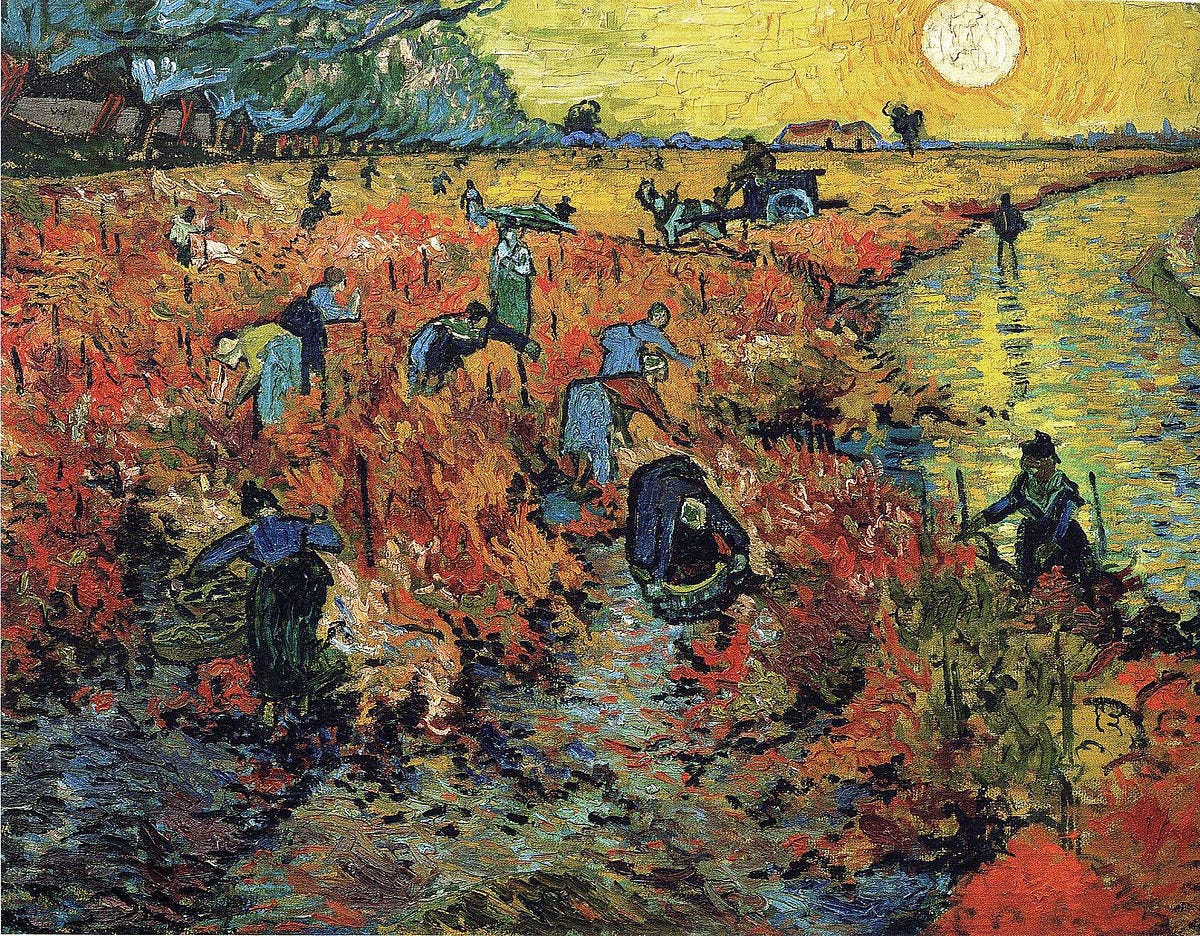

The Red Vineyard, Vincent van Gogh, 1888

One of Kierkegaard's lesser appreciated works was about wine, and it takes its name from the Latin phrase In vino veritas, meaning 'in wine, there is truth.' In dialogues reminiscent of Plato, characters, after drinking wine, engage in discussions about love:

‘The motto of the Party had been given by him as: In Vino Veritas, because there was to be speaking, to be sure, and not only conversation; but the speeches were not to be made except in vino, and no truth was to be uttered there excepting that which is in vino--when the wine is a defense of the truth and the truth a defense of the wine.’

Søren Kierkegaard, In Vino Veritas, 1845

Even Louis Pasteur seemed to recognise wine as a source of philosophical truth. For him, ‘a bottle of wine contains more philosophy than all the books in the world.’

And that's science.

Perspective Two: Wine as an escape from reality

‘It makes me see what I want to see / And be what I want to be’

Lilac Wine by Nina Simone, written by James Shelton

In Ode to a Nightingale (1819), John Keats uses wine as a symbol of escape, transcendence, and the desire to be free from the pains of mortal existence. The reference to wine, perhaps the most famous in literary history, occurs in the second stanza, where the speaker expresses a wish to drink deeply and escape the world through intoxication:

O, for a draught of vintage! that hath been

Cool'd a long age in the deep-delved earth,

Tasting of Flora and the country green,

Dance, and Provençal song, and sunburnt mirth!

O for a beaker full of the warm South,

Full of the true, the blushful Hippocrene,

With beaded bubbles winking at the brim,

And purple-stained mouth;

That I might drink, and leave the world unseen,

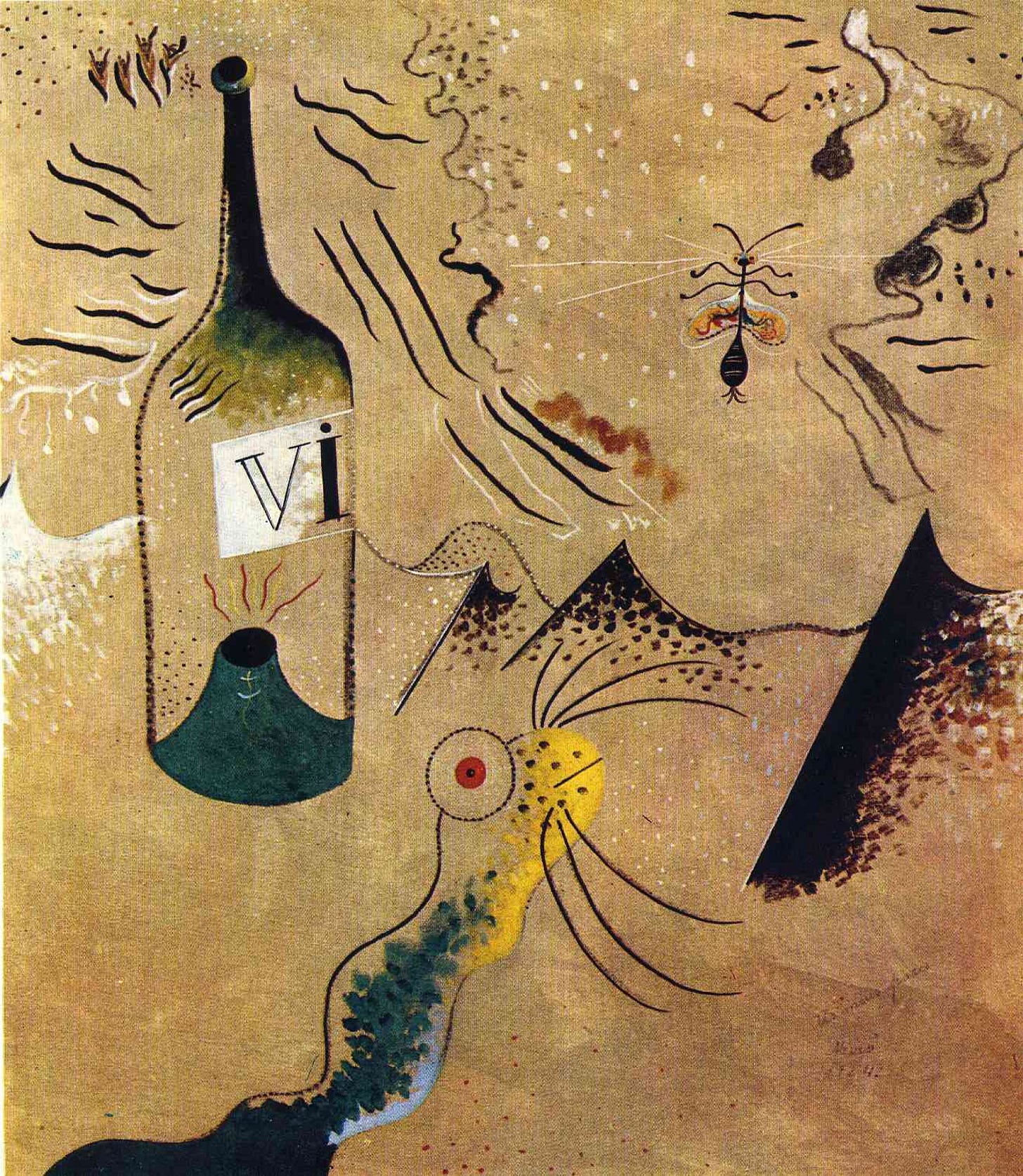

And with thee fade away into the forest dimBottiglia di vino, Joan Miró, 1924

Perspective Three: Wine and pleasure

‘Wine ... offers a greater range for enjoyment and appreciation than possibly any other purely sensory thing which may be purchased.’

Ernest Hemingway

The pleasures of wine, Herman Jacob van der Voort in de Betouw (1847-1902)

Ok, enough romance, time for some reality. Let's talk about wine for the worldly pleasure it affords. Gordon M Shepherd, in Neuroenology: How the Brain Creates the Taste of Wine (2016), points towards evidence that humans are more adapted for flavor perception than other species:

‘the cortical processing of independent streams of sensory input at successive levels of behavioral analysis is a primate, and perhaps most highly developed human, invention. It is of adaptive value in enabling humans to carry out a more detailed analysis of food and drink flavors. Humans thereby are able to differentiate themselves to a greater degree in terms of flavor preferences.’

So how do we access these powers of perception? What are the rituals we should be following to truly appreciate the depth of flavour offered by wine? Roald Dahl gives us an idea in his short story of high stakes wine identification, Taste (1951):

‘He paused, his mouth full of wine, getting the first taste, then, he permitted some of it to trickle down his throat and I saw his Adam's apple move as it passed by. But most of it he retained in his mouth. And now, without swallowing again, he drew in through his lips a thin breath of air which mingled with the fumes of the wine in the mouth and passed on down into his lungs. He held the breath, blew it out through his nose, and finally began to roll the wine around under the tongue, and chewed it, actually chewed it with his teeth as though it were bread.

It was a solemn, impressive performance, and I must say he did it well.’

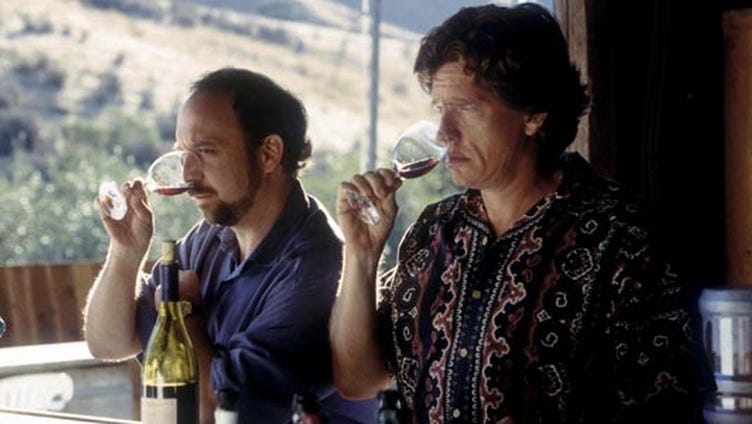

But it isn't all about taste. There's also, according to Maya in Alexander Payne's cult wine film Sideways, a human side to the appreciation of wine; perhaps it's even a metaphor for life itself:

‘I started to appreciate the life of wine, that it’s a living thing, that it connects you more to life. I like to think about what was going on the year the grapes were growing. I like the think about how the sun was shining that summer and what the weather was like. I think about all those people who tended and picked the grapes. And if it’s an old wine, how many of them must be dead by now. I love how wine continues to evolve, how if I open a bottle the wine will taste different than if I had uncorked it on any other day, or at any other moment. A bottle of wine is like life itself – it grows up, evolves and gains complexity. Then it tastes so f***ing good.’

Paul Giamatti and Thomas Haden Church in Alexander Payne’s Sideways (2004)

Maybe it is all about the taste, after all.

Perspective Four: Wine as a source of love

‘Where there is no wine there is no love.’

Euripides

In Yeats' A Drinking Song (1916), he establishes the connection between intoxication and physical attraction, but also points towards its ephemerality when he writes:

‘Wine comes in at the mouth / And love comes in at the eye; / That’s all we shall know for truth / Before we grow old and die. / I lift the glass to my mouth, / I look at you, and I sigh.’

Luncheon of the Boating Party, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1880-1881

Neruda, on the other hand, isn't quite so delicate in his aforementioned Ode to Wine:

‘My darling, suddenly / the line of your hip / becomes the brimming curve / of the wine goblet, / your breast is the grape cluster, / your nipples are the grapes, / the gleam of spirits lights your hair, / and your navel is a chaste seal / stamped on the vessel of your belly, / your love an inexhaustible / cascade of wine, / light that illuminates my senses, / the earthly splendor of life.’

Racy. But the companionship offered by the bottle needn't be sexual or even involve other people at all, as demonstrated in these beautiful and amusing lines from Drinking Alone in the Moonlight by Li Po (742–756 CE):

‘Beneath the blossoms with a pot of wine, / No friends at hand, so I poured alone; / I raised my cup to invite the moon, / Turned to my shadow, and we became three. / Now the moon had never learned about drinking, / And my shadow had merely followed my form, / But I quickly made friends with the moon and my shadow; / To find pleasure in life, make the most of the spring.’

Perspective Five: Wine and drunkenness

‘And didst thou imbibe mighty potions from the fruit of the grape (...)? And hast thou one Ache, this morning (...) appertaining unto Head, and much repentance in thy Soul forsooth?’

Mr Thwaites in Patrick Hamilton's The Slaves of Solitude

The Triumph of Bacchus, Diego Velázquez, 1628-1629

Ok, so wine in moderation can afford pleasure, bring people together, maybe even inspire some creativity or philosophising, but what happens when we fail to exercise moderation? Well, writers have had plenty to say about that, too. Let's start with Shakespeare in Othello (1604):

‘O thou invisible spirit of wine, if thou has no name to be known by, let us call thee devil….O God, that men should put an enemy in their mouths to steal away their brains! that we should, with joy, pleasance revel and applause, transform ourselves into beasts!’

Promotional Calendar for Pfungst Freres Champagne, illustrating Bacchus seated on a barrel bearing the legend In Vino Veritas, 1897

If wine is an enemy in the mouth, it is the young that are most vulnerable. They're going through enough at that age as it is! So says Plato, anyway, whose ‘Athenian’ asks in Laws (348–347 BCE):

‘Shall we not pass a law that, in the first place, no children under eighteen may touch wine at all, teaching that it is wrong to pour fire upon fire’?

There's a reason that Dionysus, Ancient Greek God of wine, also finds 'ritual madness' to be part of his remit.

Dionysus had the ability to transform humans into animals or free them from societal constraints through wine, and he was famed in particular for inspiring frenzied followers, especially women known as Maenads. Maenads worshipped the God of wine through ecstatic rites involving dancing, drinking, and wild celebrations in the forests. These rituals were often associated with both creative inspiration and dangerous madness, and I’m sure some aching heads in the morning

Bacchus by Michelangelo (1496-1497)

Not to worry. Aristotle offers us a cure; here he is on dealing with hangovers:

'It happens in the case of those suffering from the effects of drunkenness (kraipalonton) that the cabbage juice draws the wet elements, which are full of wine and still undigested, down to their stomachs, while the body chills the rest which remains in the upper part of the stomach. Once it has been chilled, the rest of the moist element can be drawn into the bladder. Thus, when each of the wet elements has been separated through the body and chilled, people are likely to be relieved of their drunkenness (akraipaloi). For wine is wet and warm.” (Problemata 873a-b)

Drunkenness, however, was not something that troubled St Thomas Aquinas in quite the same way. He comforts us with the thought that:

'Every sin has a corresponding contrary… thus timidity is opposed to daring… But no sin is opposite to drunkenness. Therefore, drunkenness is not a sin' (Summa Theologica, Q150).

I'll take that as a free pass, and anyway, in the immortal words of John Fante:

'It is better to die of drink then to die of thirst.'

John Fante, The Brotherhood of the Grape, 1977

Nice, a fun read and informative. Thank you, have a merry Autumn, Geraldine

Nicely done! Reminded me that I've been meaning to track down a copy of Roger Scruton's "I Drink Therefore I Am: A Philosopher's Guide to Wine"