Perspectives | On Windows

Strange window, your beige curtain nearly billows

Here we go again, rifling through bookshelves. We’re looking, this time, for others who’ve stared through panes of glass and wondered. My own window, as I look through it now, appears unremarkable, framing nothing but a dreary January sky and the corner of a redbrick building. It’s lucky, therefore, that this isn’t really about me at all.

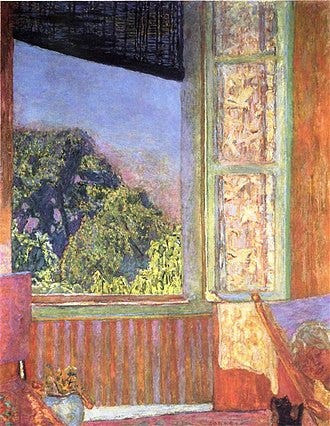

The Open Window, Pierre Bonnard, 1921

Alongside the regular essays and Perspectives, I’ve begun a small weekly commonplace for members of The Humanities Library. Upgrade if you fancy seeing what it’s all about.

Who invented glass? I mean, really, who looked at sand and thought it could be transparent? It’s a question Bill Bryson once asked:

“Among the many thousands of things that I have never been able to understand, one in particular stands out. That is the question of who was the first person who stood by a pile of sand and said, ‘You know, I bet if we took some of this and mixed it with a little potash and heated it, we could make a material that would be solid and yet transparent. We could call it glass.’ Call me obtuse, but you could stand me on a beach till the end of time and never would it occur to me to try to make it into windows.”

Notes from a Small Island, 1995

And yet here we are, surrounded by the stuff, these impossible rectangles of solid transparency. The longer you look through one, the stranger it gets:

“You propose I wait, strange window, your beige curtain nearly billows. O window, should I accept your offer or, window, defend myself? What should I wait for?

A window is the perfect vehicle for suggesting unanswered questions, for opening the way to a vastness that is rich in part because it will never be fully deciphered.”

Rainer Maria Rilke

The Balcony Room, Adolph Menzel, 1845

They’re certainly tricky customers, these windows. They aren’t always very obliging about opening, and what presses against them isn’t always comprehensible:

“I rose and endeavoured to unhasp the casement. The hook was soldered into the staple: a circumstance observed by me when awake, but forgotten. ‘I must stop it, nevertheless!’ I muttered, knocking my knuckles through the glass, and stretching an arm out to seize the importunate branch; instead of which, my fingers closed on the fingers of a little, ice-cold hand! The intense horror of nightmare came over me: I tried to draw back my arm, but the hand clung to it, and a most melancholy voice sobbed, ‘Let me in—let me in!’ ‘Who are you?’ I asked, struggling, meanwhile, to disengage myself. ‘Catherine Linton,’ it replied, shiveringly (why did I think of Linton? I had read Earnshaw twenty times for Linton); ‘I’m come home: I’d lost my way on the moor!’”

Wuthering Heights, Emily Brontë, 1847

But windows frame our view even when they’re not haunted. Maurice Merleau-Ponty sees something fundamental in his:

“It is true that external objects too never turn one of their sides to me without hiding the rest, but I can at least freely choose the side which they are to present to me. They could not appear otherwise than in perspective, but the particular perspective which I acquire at each moment is the outcome of no more than physical necessity, that is to say, of a necessity which I can use and which is not a prison for me: from my window only the tower of the church is visible, but this limitation simultaneously holds out the promise that from elsewhere the whole church could be seen. It is true, moreover, that if I am a prisoner the church will be restricted, for me, to a truncated steeple. If I did not take off my clothes I could never see the inside of them, and it will in fact be seen that my clothes may become appendages of my body. But this fact does not prove that the presence of my body is to be compared to the de facto permanence of certain objects, or the organ compared to a tool which is always available. It shows that conversely those actions in which I habitually engage incorporate their instruments into themselves and make them play a part in the original structure of my own body. As for the latter, it is my basic habit, the one which conditions all the others, and by means of which they are mutually comprehensible. Its permanence near to me, its unvarying perspective are not a de facto necessity, since such necessity presupposes them: in order that my window may impose upon me a point of view of the church, it is necessary in the first place that my body should impose upon me one of the world; and the first necessity can be merely physical only in virtue of the fact that the second is metaphysical; in short, I am accessible to factual situations only if my nature is such that there are factual situations for me.”

Phenomenology of Perception, 1945

The Window, Édouard Vuillard, 1894

Raymond Carver sees in his window a moment of transformation, however brief:

“A storm blew in last night and knocked out / the electricity. When I looked / through the window, the trees were translucent. / Bent and covered with rime. A vast calm / lay over the countryside. / I knew better. But at that moment / I felt I’d never in my life made any / false promises, nor committed / so much as one indecent act. My thoughts / were virtuous. Later on that morning, / of course, electricity was restored. / The sun moved from behind the clouds, / melting the hoarfrost. / And things stood as they had before.”

The Window

D.H. Lawrence was another window gazer:

“The pine-trees bend to listen to the autumn wind as it mutters / Something which sets the black poplars ashake with hysterical laughter; / While slowly the house of day is closing its eastern shutters.

Further down the valley the clustered tombstones recede, / Winding about their dimness the mist’s grey cerements, after / The street lamps in the darkness have suddenly started to bleed.

The leaves fly over the window and utter a word as they pass / To the face that leans from the darkness, intent, with two dark-filled eyes / That watch for ever earnestly from behind the window glass.”

At the Window

Sōseki and Sandburg, meanwhile, found something gentler in windows at night:

“The lamp once out / Cool stars enter / The window frame”

Natsume Sōseki

Man Reading at a Window, François-Marius Granet, 19th c.

“Night from a railroad car window / Is a great, dark, soft thing / Broken across with slashes of light”

Carl Sandburg

Apologies for interrupting, but readers drawn to this theme may also enjoy earlier collections on Home, Isolation or Mirrors, gathered in the archive for library members.

It seems we’re all, at heart, nothing but a bunch of peeping toms. Stella had it right in Hitchcock’s Rear Window:

Stella: We’ve become a race of Peeping Toms. What people ought to do is get outside their own house and look in for a change. Yes sir. How’s that for a bit of homespun philosophy?

L.B. Jefferies: Reader’s Digest, April 1939.

Stella: Well, I only quote from the best.

Screenplay for Rear Window, 1954

Baudelaire took Stella’s advice long before she gave it. He wandered Paris looking in at windows, not out through them:

“Looking from outside into an open window one never sees as much as when one looks through a closed window. There is nothing more profound, more mysterious, more pregnant, more insidious, more dazzling than a window lighted by a single candle. What one can see out in the sunlight is always less interesting than what goes on behind a windowpane. In that black or luminous square life lives, life dreams, life suffers.”

Paris Spleen, 1869

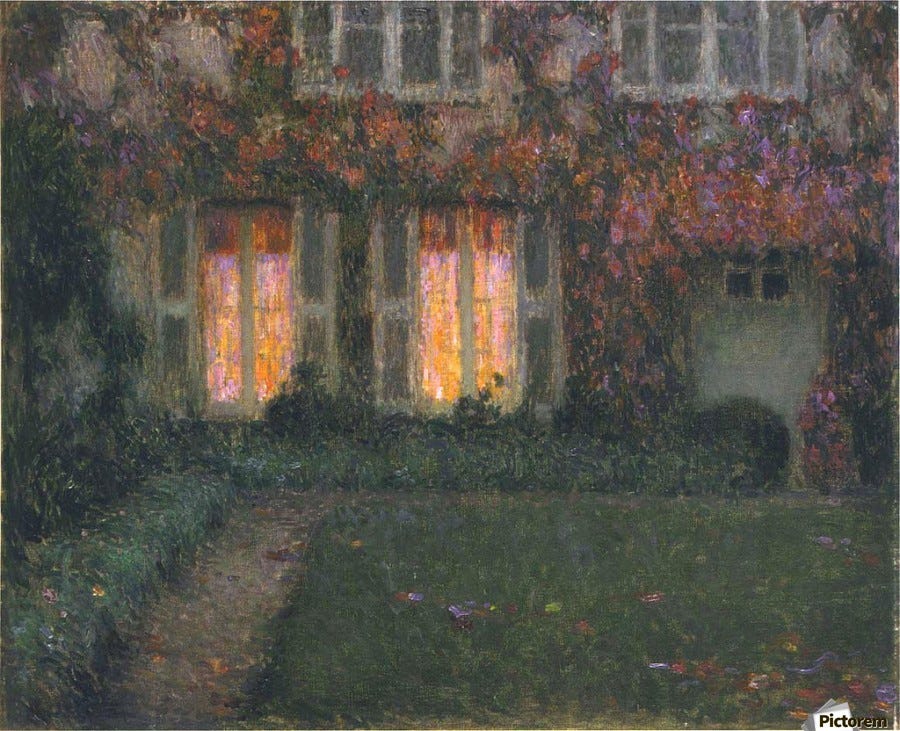

The Window in Autumn, Henri Le Sidaner, c1908

So we look in, we look out, we watch and are watched. But what if the window isn’t really about seeing at all? What if they’re just a place where you stand, unable to move:

“If our life were an eternal standing by the window, if we could remain there for ever, like hovering smoke, with the same moment of twilight forever paining the curve of the hills... If we could remain that way for beyond for ever! If at least on this side of the impossible we could thus continue, without committing an action, without our pallid lips sinning another word!

Look how it’s getting dark!... The positive quietude of everything fills me with rage, with something that’s a bitterness in the air I breathe. My soul aches... A slow wisp of smoke rises and dissipates in the distance... A restless tedium makes me think no more of you...

All so superfluous! We and the world and the mystery of both.”

The Book of Disquiet, Fernando Pessoa

Unless (and here’s a thought) you simply fling the thing open:

“Set wide the window. Let me drink the day.”

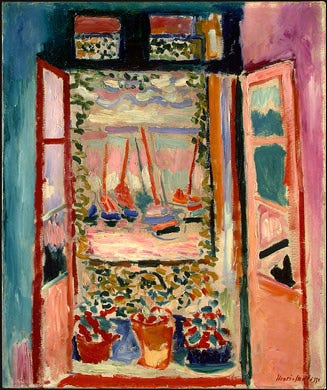

The Open Window, Henri Matisse, 1905

Have a lovely week! And do, if you can, spare a moment or two to gaze out of a window

Started reading this and was enjoying myself then closed the app and today substack reminded me to finish reading. Love a good meander through enjoyable writing….

This was such an inspiring read. As a photographer, I’ve always seen windows as more than just sources of light; they are powerful tools for framing and perspective. I often play with window angles in my own work to tell a deeper story, so seeing these literary takes on the 'mysterious square' really resonated with me. It’s a beautiful reminder that what we choose to frame—and how we angle our gaze—defines the world we see.