The train is one of modern civilization’s most compelling symbols: industrial yet intimate, linear yet unpredictable; noisy, grimy, romantic, efficient; bound to ideas of escape, momentum, transition, isolation, the ache of departure, and the thrill of arrival.

For over a century, trains have thundered through the pages of literature and the canvases of artists. Here's a few of my favourites, and I'd love to hear some of yours in the comments.

La Gare Saint-Lazare, Paul-César Helleu, 1885

‘In the winter, we will leave in a small pink railway carriage / With blue cushions. We will be comfortable. / A nest of mad kisses lies In each soft corner. / You will close your eyes, in order not to see, through the glass, / The evening shadows making faces. / Those snarling monstrosities, a populace / Of black demons and black wolves. / Then you will feel your cheek scratched... / A little kiss, like a mad spider, Will run around your neck... / And you will say to me: "Get it!" as you bend your neck - / And we will take a long time to find that creature - / Which travels a great deal...’

Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891), A Dream for Winter

‘All through the ghostly stillness of the land the train made on forever its tremendous noise fused of a thousand sounds and haunted by the spell of time. And that sound evoked for him a million images: old songs, old faces and forgotten memories, and all strange, wordless, and unspoken things men know and live and feel, and never find a language for, the legend of dark time, the sad brevity of their days, the strange and bitter miracle of life itself. And through the thousand rhythms of this one design he heard again, as he had heard ten thousand times in childhood, the pounding wheel, the tolling bell, the whistle wail. Far, faint, and lonely as a dream, it came to him again through that huge spell of time and silence and the earth, evoking for him, as it had always done, its tongueless prophecy of life, its wild and secret cry of joy and pain, and its intolerable promises of the new lands, morning and a shining city.’

Thomas Wolfe, Boom Town, 1934

That Whitsun, I was late getting away: / Not till about / One-twenty on the sunlit Saturday / Did my three-quarters-empty train pull out, / All windows down, all cushions hot, all sense / Of being in a hurry gone. We ran / Behind the backs of houses, crossed a street / Of blinding windscreens, smelt the fish-dock; thence / The river’s level drifting breadth began, / Where sky and Lincolnshire and water meet.

‘All afternoon, through the tall heat that slept / For miles inland, / A slow and stopping curve southwards we kept. / Wide farms went by, short-shadowed cattle, and / Canals with floatings of industrial froth; / A hothouse flashed uniquely: hedges dipped / And rose: and now and then a smell of grass / Displaced the reek of buttoned carriage-cloth / Until the next town, new and nondescript, / Approached with acres of dismantled cars.’

Philip Larkin, The Whitsun Weddings, 1964

Lordship Lane Station, Dulwich, Camille Pissarro, 1871

‘The railroad track is miles away, / And the day is loud with voices speaking, / Yet there isn't a train goes by all day / But I hear its whistle shrieking.

All night there isn't a train goes by, / Though the night is still for sleep and dreaming, / But I see its cinders red on the sky, / And hear its engine steaming.

My heart is warm with the friends I make, / And better friends I'll not be knowing; / Yet there isn't a train I wouldn't take, / No matter where it's going.’

Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892-1960), Travel

‘'How fair, how strange,' said Bernard, 'glittering, many-pointed and many-domed London lies before me under mist. Guarded by gasometers, by factory chimneys, she lies sleeping as we approach. She folds the ant-heap to her breast. All cries, all clamour, are softly enveloped in silence. Not Rome herself looks more majestic. But we are aimed at her. Already her maternal somnolence is uneasy. Ridges fledged with houses rise from the mist. Factories, cathedrals, glass domes, institutions and theatres erect themselves. The early train from the north is hurled at her like a missile. We draw a curtain as we pass. Blank expectant faces stare at us as we rattle and flash through stations. Men clutch their newspapers a little tighter, as our wind sweeps them, envisaging death. But we roar on. We are about to explode in the flanks of the city like a shell in the side of some ponderous, maternal, majestic animal. She hums and murmurs; she awaits us.’

Virginia Woolf, The Waves, 1931

The Lights of London, Cannon Street Station, c.1924, Samuel Harry Hancock

‘One night, during a trip abroad, in the fall of 1903, I recall kneeling on my (flattish) pillow at the window of a sleeping car (probably on the long-extinct Mediterranean Train de Luxe, the one whose six cars had the lower part of their body painted in umber and the panels in cream) and seeing with an inexplicable pang, a handful of fabulous lights that beckoned to me from a distant hillside.’

Vladimir Nabokov, Speak, Memory, 1951

‘The train at Pershore station was waiting that Sunday night / Gas light on the platform, in my carriage electric light, / Gas light on frosty evergreens, electric on Empire wood, / The Victorian world and the present in a moment's neighbourhood.’

John Betjeman (1906-1984), Pershore Station, or A Liverish Journey First Class

Chair Car, Edward Hopper, 1965

‘The aristocrats, if such they could be called, generally hated the whole concept of the train on the basis that it would encourage the lower classes to move about and not always be available.’

Terry Pratchett, Raising Steam (Discworld, #40; Moist von Lipwig, #3), 2013

‘In the rushing reverberating express, noise was so regular that it was the equivalent of silence, movement was so continuous that after a while the mind accepted it as stillness’

Graham Greene, Stamboul Train, 1932

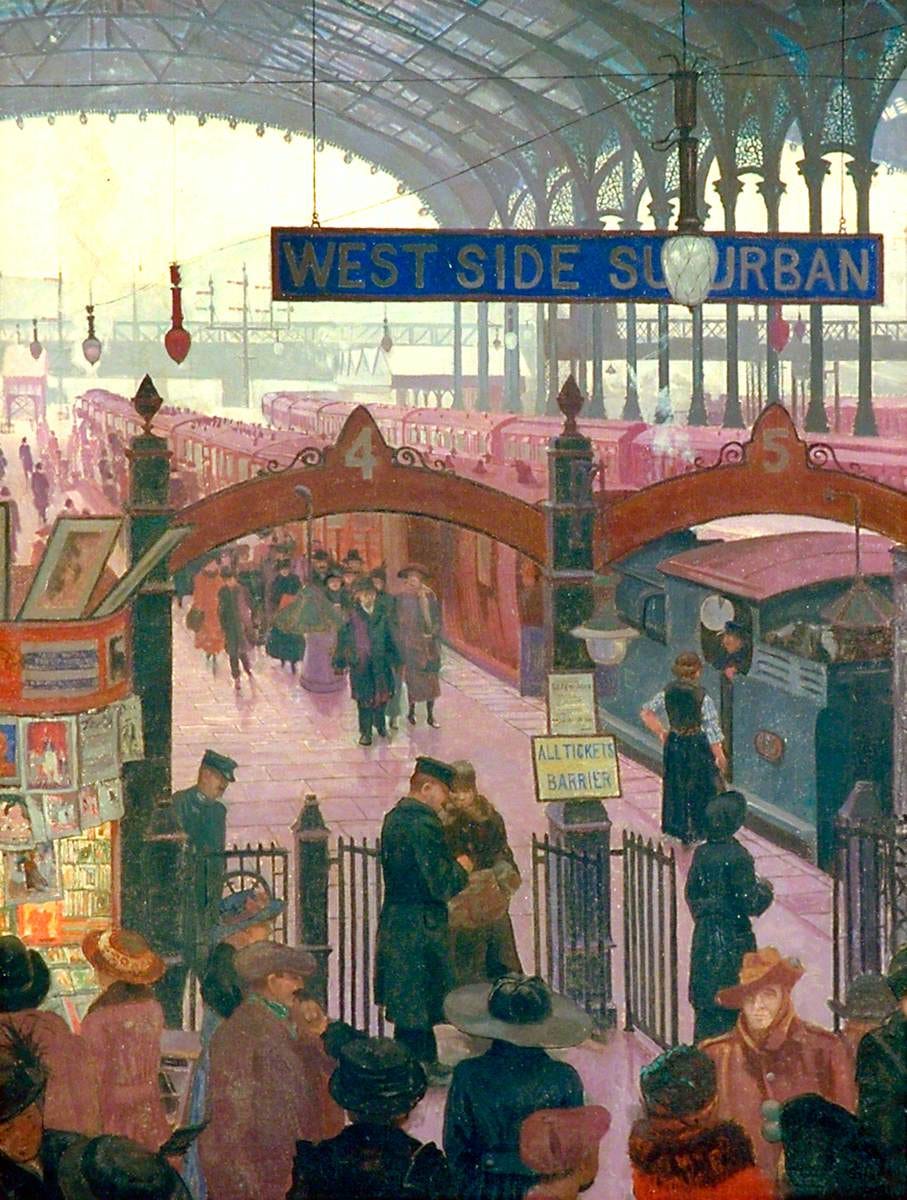

Cannon Street Station, Algernon Talmage, 1908

‘Perhaps the most beautiful part of America is the West, to reach which, however, involves a journey by rail of six days, racing along tied to an ugly tin-kettle of a steam engine. I found but poor consolation for this journey in the fact that the boys who infest the cars and sell everything that one can eat-or should not eat-were selling editions of my poems vilely printed on a kind of grey blotting paper, for the low price of ten cents.’

Oscar Wilde, Impressions of America,

‘It is life in slow motion, / it's the heart in reverse, / it's a hope-and-a-half: / too much and too little at once. / It's a train that suddenly / stops with no station around, / and we can hear the cricket, / and, leaning out the carriage / door, we vainly contemplate / a wind we feel that stirs / the blooming meadows, the meadows / made imaginary by this stop.’

The Wait, Rainer Maria Rilke, 1906

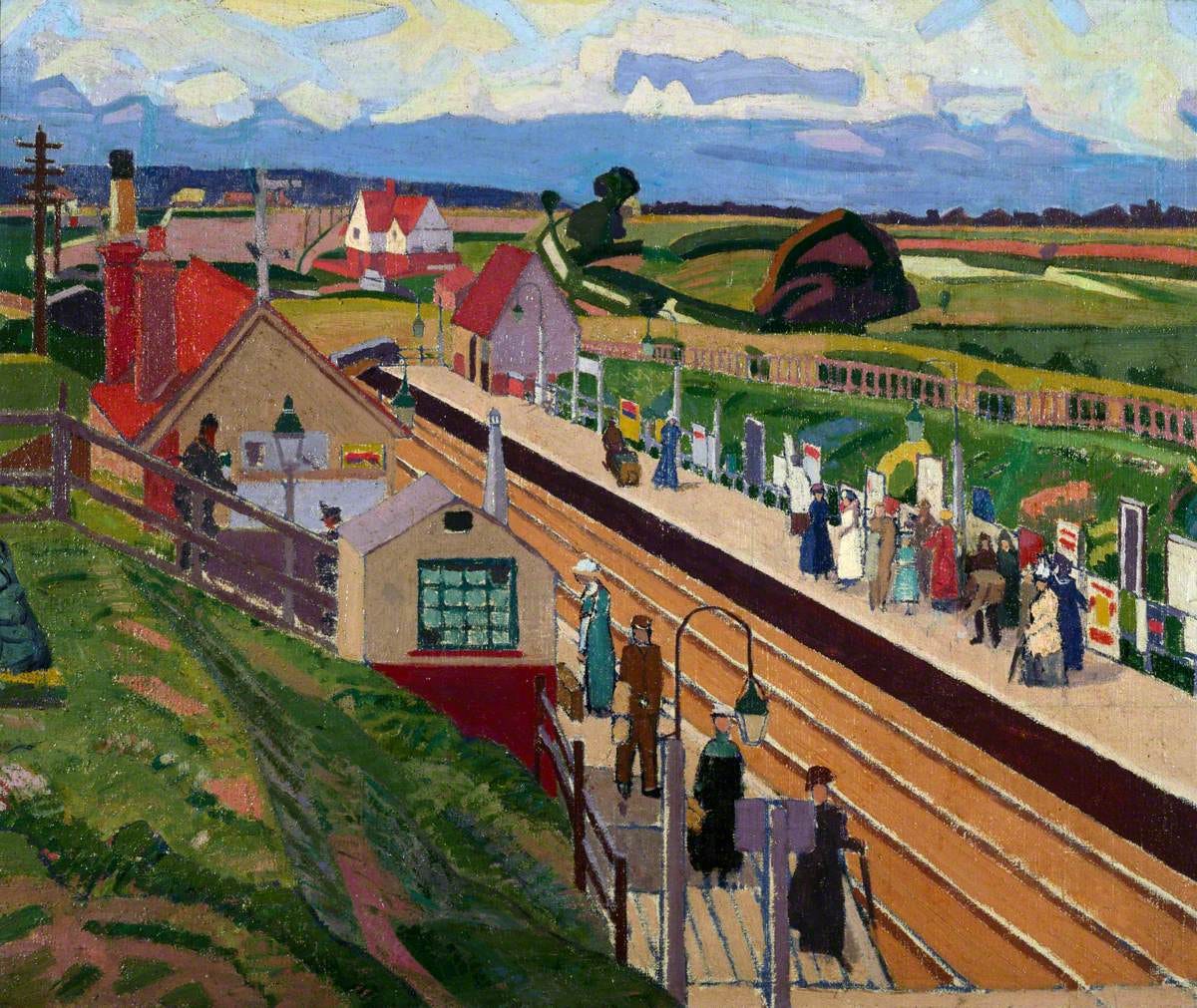

Letchworth Station, Spencer Gore, 1912

‘I like to see it lap the Miles - / And lick the Valleys up - / And stop to feed itself at Tanks - / And then - prodigious step

Around a Pile of Mountains - / And supercilious peer / In Shanties - by the sides of Roads - / And then a Quarry pare

To fit its sides / And crawl between / Complaining all the while / In horrid - hooting stanza - / Then chase itself down Hill -

And neigh like Boanerges - / Then - prompter than a Star / Stop - docile and omnipotent / At it's own stable door -’

Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), I like to see it lap the Miles

‘I am refreshed and expanded when the freight train rattles past me.’

Henry David Thoreau, Walden, 1854

‘Thee for my recitative, / Thee in the driving storm even as now, the snow, the winter-day declining, / Thee in thy panoply, thy measur’d dual throbbing and thy beat convulsive, / Thy black cylindric body, golden brass, and silvery steel, / Thy ponderous side-bars, parallel and connecting rods, gyrating, shuttling at thy sides, / Thy metrical, now swelling pant and roar, now tapering in the distance, / Thy great protruding head-light fix’d in front, / Thy long, pale, floating vapor-pennants, tinged with delicate purple, / The dense and murky clouds out-belching from thy smoke-stack, / Thy knitted frame, thy springs and valves, the tremulous twinkle of thy wheels’

Walt Whitman (1819-1892), To a Locomotive in Winter

Central Station, Adolphe Valette, 1910-1911

‘To the jaded and the toilworn, therefore, we would say, close your books, leave the desk, fly the study, hasten to the nearest railway station, and take a return ticket for twelve or fifteen miles. On arriving at your destination, scud down the green lanes and across the fields, setting out at a brisk pace and maintaining it until you return to the departure station in a couple of hours' time. The journey homeward will appropriately cap the achieve-ment; which, although we do not vaunt as a panacea for all the ills of life, we nevertheless declare, from experiences to be one of the very best repairers of health and restorers of spirits.’

Anon., The Railway Traveller's Handy Book, 1862

‘Sometimes, down in the subway, a train Maxine's riding on will slowly be overtaken by a local or an express on the other track, and in the darkness of the tunnel, as the windows of the other train move slowly past, the lighted panels appear one by one, like a series of fortune-telling cards being dealt and slid in front of her. The Scholar, The Unhoused, The Warrior Thief, The Haunted Woman... After a while Maxine has come to understand that the faces framed in these panels are precisely those out of all the city millions she must in the hour be paying most attention to, in particular those whose eyes actually meet her own-they are the day's messengers from whatever the Beyond has for a Third World, where the days are assembled one by one under non-union conditions. Each messenger carrying the props required for their character, shopping bags, books, musical instruments, arrived here out of darkness, bound again into darkness, with only a minute to deliver the intelligence Maxine needs. At some point naturally she begins to wonder if she might not be performing the same role for some face looking back out another window at her.’

Thomas Pynchon, Bleeding Edge, 2013

Irish Emigrants Waiting for the Train, Erskine Nicol, 1864

‘A goods train was approaching. The platform shook, and it seemed to her as if she were again in the train.

Suddenly remembering the man who had been run over the day she first met Vronsky, she realized what she had to do. Quickly and lightly descending the steps that led from the water-tank to the rails, she stopped close to the passing train. She looked at the bottom of the trucks, at the bolts and chains, and large iron wheels of the slowly-moving front truck, and tried to estimate the middle point between the front and back wheels, and the moment when that point would be opposite her.

She wanted to fall half-way between the wheels of the front truck, which was drawing level with her, but the little red handbag which she began to take off her arm delayed her, and then she was too late. The middle had passed her. She was obliged to wait for the next truck. A feeling seized her like that she had experienced when preparing to enter the water in bathing, and she crossed herself. The familiar gesture of making the sign of the cross called up a whole series of girlish and childish memories, and suddenly the darkness, that obscured everything for her, broke, and life showed itself to her for an instant with all its bright past joys. But she did not take her eyes off the wheels of the approaching second truck, and at the very moment when the midway point between the wheels drew level, she threw away her red bag, and drawing her head down between her shoulders threw herself forward on her hands under the truck, and with a light movement as if preparing to rise again, immediately dropped on her knees. And at the same moment she was horror-struck at what she was doing. ‘Where am I? What am I doing? Why?’ She wished to rise, to throw herself back, but something huge and relentless struck her on her head and dragged her down. ‘God forgive me everything!’ she said, feeling the impossibility of struggling… A little peasant muttering something was working at the rails. The candle, by the light of which she had been reading that book filled with anxieties, deceptions, grief and evil, flared up with a brighter light, lit up for her all that had before been dark, crackled, began to flicker, and went out for ever.’

Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina, 1878

‘You should always have something sensational to read in the train.’

Oscar Wilde, The Importance of Being Earnest, 1895

Liverpool Street Station, Marjorie Sherlock, 1917

There's something so magical about trains. I love this description of a Paris train station in Bowen's The House in Paris:

“Where are we going now? The station is sounding, resounding, full of steam caught on light and arches of dark air: a temple to the intention to go somewhere. Sustained sound in the shell of stone and steel, racket and running, impatience and purpose, make the soul stand still like a refugee, clutching all it has got, asking: “I am where?”

Trains and train stations also play a significant part in Proust's In Search of Lost Time. He mentioned that the train stations are a society place in its own, where the passengers would gather in between journey. One long scene In Book 4 Sodom Gomorrah took place during the train journey that took him and other passengers to the Verdurin's