One of the souls Dante places in his second circle of hell, the one reserved for the lustful, is Francesca da Rimini, an Italian medieval noblewoman who was murdered by her husband after he discovered her affair with his brother.

Alongside her lover Paolo, Rimini's eternal suffering takes the form of being perennially swept up in a violent storm, mirroring the way in which they were swept up in the winds of their uncontrollable lust. When she tells the story of her affair, she has this to say about her memories:

'Nessun maggior dolore che ricordarsi del tempo felice nella miseria'

Or

'There is no greater sorrow than to recall a happy time when miserable'

Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy: Inferno, Canto V, lines 121–123.

Her punishment isn't tempered by her escape into the happiness of memory, it's made worse. Worse because what she had with Paolo is in the past. Worse because of the absence of love in her present. Worse because what she felt can never be recovered in the future.

The Welsh have a word for this. It's Hiraeth, which refers to a longing for a person, a place or a time that, crucially, cannot be returned to. It's a longing the chief attribute of which is its unattainability, a pull on the heart for something irretrievably lost.

I get something similar when I think of my first year of university. Playing pool in a pub in the middle of a weekday, treating a can of baked beans as adequate sustenance for a full meal, doing the laundry in the dead of night with drunk fellow students stumbling back to their dorms.

I could go back to study as a mature student, sure, but that sense of exhilarating, anything is possible, my-boundaries-are-what-I-make-them optimism is something that is lost forever. Beans out of the can is a ritual that is accompanied by a wholely different set of associations when you're pushing middle age.

All of this is to say that my theme this week is hiraeth, or at least it's closest English translation. Deriving from the Greek nostos, meaning 'return' and algos, meaning 'suffering,' the English word nostalgia refers to the suffering caused by our desire to return.

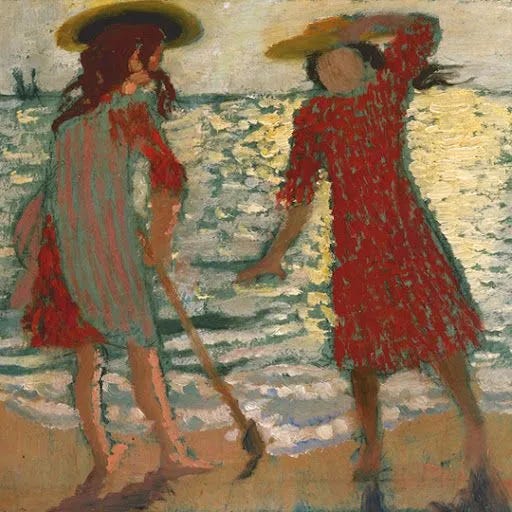

Boys Playing on the Shore, 1884, Albert Edelfelt

Cultural theorist Svetlana Boym is fascinating on nostalgia. She describes it thus:

‘nostalgia appears to be a longing for a place but is actually a yearning for a different time—the time of our childhood, the slower rhythms of our dreams. In a broader sense, nostalgia is a rebellion against the modern idea of time, the time of history and progress. The nostalgic desires to obliterate history and turn it into private or collective mythology, to revisit time as space, refusing to surrender to the irreversibility of time that plagues the human condition. Hence the “past of nostalgia,” to paraphrase Faulkner, is not “even the past.” It could merely be another time, or slower time. Time out of time, not encumbered by appointment books.’

The Allée of the Chestnut Trees at the Jas de Bouffan, Paul Cézanne, 1886–87

Boym divides nostalgia into two types—restorative and reflective. Restorative nostalgia focuses on the re-creation of a lost past, while reflective nostalgia meditates on the irretrievability of the past:

‘Instead of a magic cure for nostalgia, I will offer a tentative typology and distinguish between two main types of nostalgia: the restorative and the reflective. Restorative nostalgia stresses nóstos (home) and attempts a transhistorical reconstruction of the lost home. Reflective nostalgia thrives in álgos, the longing itself, and delays the homecoming—wistfully, ironically, desperately. These distinctions are not absolute binaries, and one can surely make a more refined mapping of the gray areas on the outskirts of imaginary homelands. Restorative nostalgia does not think of itself as nostalgia, but rather as truth and tradition. Reflective nostalgia dwells on the ambivalences of human longing and belonging and does not shy away from the contradictions of modernity. Restorative nostalgia protects the absolute truth, while reflective nostalgia calls it into doubt.’

Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia, 2001

Whilst reading her definition of restorative nostalgia, which was new to me this week, I was minded to return to a text that itself holds a nostalgic place in my deeper past. Dom Casmurro by Machado de Assis (1899) opens brilliantly with a cautionary tale about what I'll now term 'restorative' nostalgia:

‘I live alone, with a servant. The house I live in is my own; I decided to have it built, prompted by such a personal, private motive that I am embarrassed to put it in print, but here it goes. One day, quite a few years ago, I had the notion of building in Engenho Novo a replica of the house I had been brought up in on the old Rua de Matacavalos, and giving it the same aspect and layout as the other one, which has now disappeared. Builder and decorator understood my instructions perfectly: it is the same two-story building, three windows at the front, a verandah at the back, the same bedrooms and living rooms. In the main room, the paintings on the ceiling and walls are more or less the same, with garlands of small flowers and large birds, at intervals, carrying them in their beaks. In the four corners of the ceiling, the figures of the seasons, and at the center of the walls, medallions of Caesar, Augustus, Nero and Massinissa, with their names underneath ... Why these four characters I do not understand. When we moved into the Matacavalos house, it was already decorated in this way: it had been done in the previous decade. It must have been the taste of the time to put a classical flavor and ancient figures into paintings done in America. The rest is also analogous to this and similar to it. I have a small garden, flowers, vegetables, a casuarina tree, a well and a washing-stone. I use old china and old furniture. Finally, there is, now as in the old days, the same contrast between life inside the house, which is placid, and the noisy world outside.

Clearly my aim was to tie the two ends of life together, and bring back youth in old age. Well, sir, I managed neither to reconstruct what was there, nor what I had been. Everywhere, though the surface may be the same, the character is different. If it was only others that were missing, all well and good: one gets over the loss of other people as best one can; but I myself am missing, and that lacuna is all-important.’

Also alive to the complex and imperfect ability of nostalgia to truly recapture the past is Gabriel Garcia Marquez in Love in the Time of Cholera (1985):

‘He was still too young to know that the heart's memory eliminates the bad and magnifies the good, and that thanks to this artifice we manage to endure the burden of the past. But when he stood at the railing of the ship... only then did he understand to what extent he had been an easy victim to the charitable deceptions of nostalgia.’

Paul Klee, Memory of a Bird, 1932

This most deceptive of emotions can be brought on in many ways. It can creep up like damp in an unused room, unnoticed until the air starts to feel thicker, or it can come on as instantly as the opening of a trap door. So it is in the most famous passage about memory in all of literature. I feel like I've quoted from this text a lot already in previous articles, but it would be remiss of us, in an article about nostalgia in literature, not to reach for some madeleine cake:

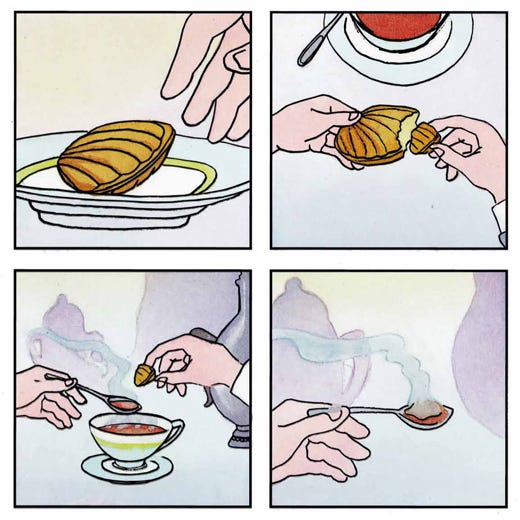

‘No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shudder ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, something isolated, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. And at once the vicissitudes of life had become indifferent to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory – this new sensation having had on me the effect which love has of filling me with a precious essence; or rather this essence was not in me it was me. ... Whence did it come? What did it mean? How could I seize and apprehend it? ... And suddenly the memory revealed itself. The taste was that of the little piece of madeleine which on Sunday mornings at Combray (because on those mornings I did not go out before mass), when I went to say good morning to her in her bedroom, my aunt Léonie used to give me, dipping it first in her own cup of tea or tisane. The sight of the little madeleine had recalled nothing to my mind before I tasted it. And all from my cup of tea.’

Marcel Proust, À la recherche du temps perdu, 1913-1927

From Stéphane Heuet's graphic novel version of À la recherche du temps perdu

More famous reflections brought about by the taste of food can be found in Tolstoy's The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886):

‘Pictures of his past rose before him one after another. They always began with what was nearest in time and then went back to what was most remote—to his childhood—and rested there. If he thought of the stewed prunes that had been offered him that day, his mind went back to the raw shrivelled French plums of his childhood, their peculiar flavour and the flow of saliva when he sucked their stones, and along with the memory of that taste came a whole series of memories of those days: his nurse, his brother, and their toys.’

Nostalgic time travel can take many forms. One of the most commonly found objects of nostalgic longing is place, perhaps the small town of our youth…

‘I had expected to see the town of my mother’s memories, of her nostalgia—nostalgia laced with sighs. She had lived her lifetime sighing about Comala, about going back. But she never had. Now I had come in her place. I was seeing things through her eyes, as she had seen them. She had given me her eyes to see. Just as you pass the gate of Los Colimotes there’s a beautiful view of a green plain tinged with the yellow of ripe corn. From there you can see Comala, turning the earth white, and lighting it at night. Her voice was secret, muffled, as if she were talking to herself… Mother.’

Juan Rulfo, Pedro Paramo, 1955

Or the larger kingdoms of our imaginings:

‘Everything can be killed except nostalgia for the kingdom, we carry it in the color of our eyes, in every love affair, in everything that deeply torments and unties and tricks. Wishful thinking, perhaps; but that is just another possible definition of the featherless biped.’

Julio Cortazar, Hopscotch, 1963

Cane Chair – Outside, Richard Diebenkorn, 1959

We can also be taken back to specific people we long to see again:

‘Like no one else... you share that part of my mind that associates itself mostly with ideal things and places... The impression thinking about you gives me is very closely linked with that given me by a lonely hillside or a sunny afternoon... or books that have meant more to me than I can explain... This is grand, but still it isn't enough for this world... The earthly and obvious part of me longs to see and touch you and realise you as tangible.’

Vera Brittain, Testament of Youth, 1933

And sometimes it’s external objects, things, that our memory is pulling towards:

‘Any nostalgia I feel is literary. I remember my childhood with tears, but they’re rhythmic tears, in which prose is already being formed. I remember it as something external, and it comes back to me through external things; I remember only external things. It’s not the stillness of evenings in the country that endears me to the childhood I spent there, it’s the way the table was set for tea, it’s the way the furniture was arranged in the room, it’s the faces and physical gestures of the people. I feel nostalgia for scenes.’

Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet, 1982

The Blue Door, Raymond Wintz, 1925

Another possibility is nostalgia for feelings. In the gut-punchingly brilliant One Moonlit Night by Caradog Pritchard (1961), the narrator's longing is for his ability to feel anything at all with the intensity he did in childhood, even the awful feelings:

‘And then I started crying. Not crying like I used to years ago whenever I fell down and hurt myself; and not crying like I used to at some funerals either; and not crying like when Mam went home and left me in Guto’s bed at Bwlch Farm ages ago. But crying just like being sick. Crying without caring who was looking at me. Crying as though it was the end of the world. Crying and screaming the place down, not caring who was listening. And glad to be crying, the same way some people are glad when they’re singing, and others are glad when they’re laughing. Dew, I’d never cried like that before, and I’ve never cried like that since, either. I’d love to be able to cry like that again, just once more.’

How is it possible to feel nostalgia for such a moment of pain? Perhaps the answer lies in the formative nature of such experiences. Cherished memories can act as emotional anchors that guide and sustain a person throughout life:

‘You are told a lot about your education, but some beautiful, sacred memory, preserved since childhood, is perhaps the best education of all. If a man carries many such memories into life with him, he is saved for the rest of his days. And even if only one good memory is left in our hearts, it may also be the instrument of our salvation one day.’

The Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, 1880

On the Beach (Two Girls Against the Light), Maurice Denis, 1892

Here, memory ceases to be passive recollection and becomes an active force, supporting the life that rests upon it. So too for Virginia Woolf in her essay A Sketch of the Past (1939):

‘If life has a base that it stands upon, if it is a bowl that fills and fills and fills – then my bowl without a doubt stands upon this memory. It is of lying half asleep, half awake, in bed in the nursery at St Ives. It is of hearing the waves breaking, one, two, one, two, behind a yellow blind. It is of hearing the blind draw its little acorn across the floor as the wind blew the blind out. It is of lying and hearing this splash and seeing this light, and feeling, it is impossible that I should be here; of feeling the purest ecstasy I can conceive.’

Wind from the Sea, Andrew Wyeth, 1947

Perhaps the real beauty of nostalgia is in recognising the significance of moments, people, places, the importance of which, at the time, was lost to a consciousness too immersed in the immediacy of experience to grasp its full depth. Woolf again in her diaries:

‘I can only note that the past is beautiful because one never realises an emotion at the time. It expands later, and thus we don't have complete emotions about the present, only about the past.’

What's so wrong with living in the fully realised emotions of the past as a defense against the fragmented and overwhelming present? Maybe remaining connected to a time when we could really feel, before the habits and routines of adulthood dulled the senses, is not escapism, but a way of grounding ourselves in something real when the present feels too chaotic to grasp.

‘All grown-ups were once children… but only a few remember it.’

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince, 1943

This was heartbreakingly beautiful. A magical piece - thank you!

Love Boym, love this, thank you