I've gained a great many things since joining Substack a few months ago. I find a strange satisfaction in adhering to the weekly deadline, however unnecessary and self imposed it may be. I'm prompted by its looming presence to press on with that bit of reading I'd have otherwise neglected or to spend an evening writing that would otherwise have been lost to whatever the Netflix algorithm had selected to beam into my passive consciousness.

The sketching out of the latest essay (if that's the right word for what I'm doing) - highlighting, cutting, reordering, chopping - is, it turns out, a fine way of preserving a sense of order, a sort of bulwark against chaos. I'm starting to feel like I'll be doing this in perpetuity, regardless of the presence of any subscribers, the way others turn to watercolours or embroidery.

But it's not all positivity. In the shadow of these neatly arranged and happy blocks of intention, something else is being neglected. I haven't written in my diary for months, the habit of turning to it in the evening quietly disappearing to be replaced by this more “productive” business of structured writing.

Woman at a Writing-Desk, Lesser Ury, 1898

It's starting to make me feel anxious. I'm starting to feel like, without my scattered notes about the day's events, I've somehow lost all of this time, as if the lack of a poorly expressed handful of bullet points means those moments didn’t really happen. It seems I need a record of my life, in all its paternal extravagance - went to park, bought sticker book, fell asleep on the sofa at 8.30 - to remind myself that it actually took place at all.

It’s a strange kind of anxiety, but I know I’m not alone in feeling it. The French artist Eugène Delacroix wrestled with a similar tension:

‘I have hurriedly re-read the whole of my Journal. I regret the gaps. I feel as though I were still master of the days I have recorded, even though they are past, whereas those not mentioned in the pages are as though they had never been.

How low have I fallen? Am I then so weak that those flimsy pages will be the only record of my life remaining to me? The future is all blackness. The past, where I have not recorded it, is the same.’

The Diary of Eugène Delacroix, Spring 1824

Model Writing Postcards, Carl Larsson, 1906

The Humanities Library 'law' that seems to be emerging is that the longer I waffle on, the probability of me mentioning Virginia Woolf approaches 1, so let's get it out of the way early. She has a great discussion of what a (her) diary should include, which seems like as good a place as any to start:

‘What sort of diary should I like mine to be? Something loose knit but not slovenly, so elastic that it will embrace anything solemn, slight or beautiful that comes into my mind. I should like it to resemble some deep old desk or capacious hold-all in which one flings a mess of odds and ends without looking them through. I should like to come back after a year or two and find that the collection had sorted itself and refined itself and coalesced.’

A Writer’s Diary, April 1919

That Woolf's diaries are so beautiful seems appropriate - what else would we expect to find from such a brilliant mind? That mine are so dull, perhaps, is equally appropriate. But our diaries should reflect us - they're personal documents, written with no audience in mind, fulfilling a different need for everyone who writes them.

‘Writing in a diary is a really strange experience for someone like me. Not only because I’ve never written anything before, but also because it seems to me that later on neither I nor anyone else will be interested in the musings of a thirteen-year-old schoolgirl. Oh well, it doesn’t matter. I feel like writing, and I have an even greater need to get all kinds of things off my chest.’

The Diary of a Young Girl, Anne Frank, 1947

For André Gide, another famous diarist, the intimate nature of a diary makes them fascinating documents at times of 'awakening' or change, when we've, as Anne Frank so delicately puts it, a 'need to get all kinds of things off [our] chest.'

‘A diary is useful during conscious, intentional, and painful spiritual evolutions. Then you want to know where you stand… An intimate diary is interesting especially when it records the awakening of ideas; or the awakening of the senses at puberty; or else when you feel yourself to be dying.’

André Gide, The journals of André Gide, 1889-1949

But for Susan Sontag, it isn't enough to simply consider the diary a vessel for personal musings - to her it's more:

‘Superficial to understand the journal as just a receptacle for one’s private, secret thoughts—like a confidante who is deaf, dumb, and illiterate. In the journal I do not just express myself more openly than I could do to any person; I create myself. The journal is a vehicle for my sense of selfhood. It represents me as emotionally and spiritually independent. Therefore (alas) it does not simply record my actual, daily life but rather — in many cases — offers an alternative to it.’

Susan Sontag, Reborn: Early Diaries 1947-1963

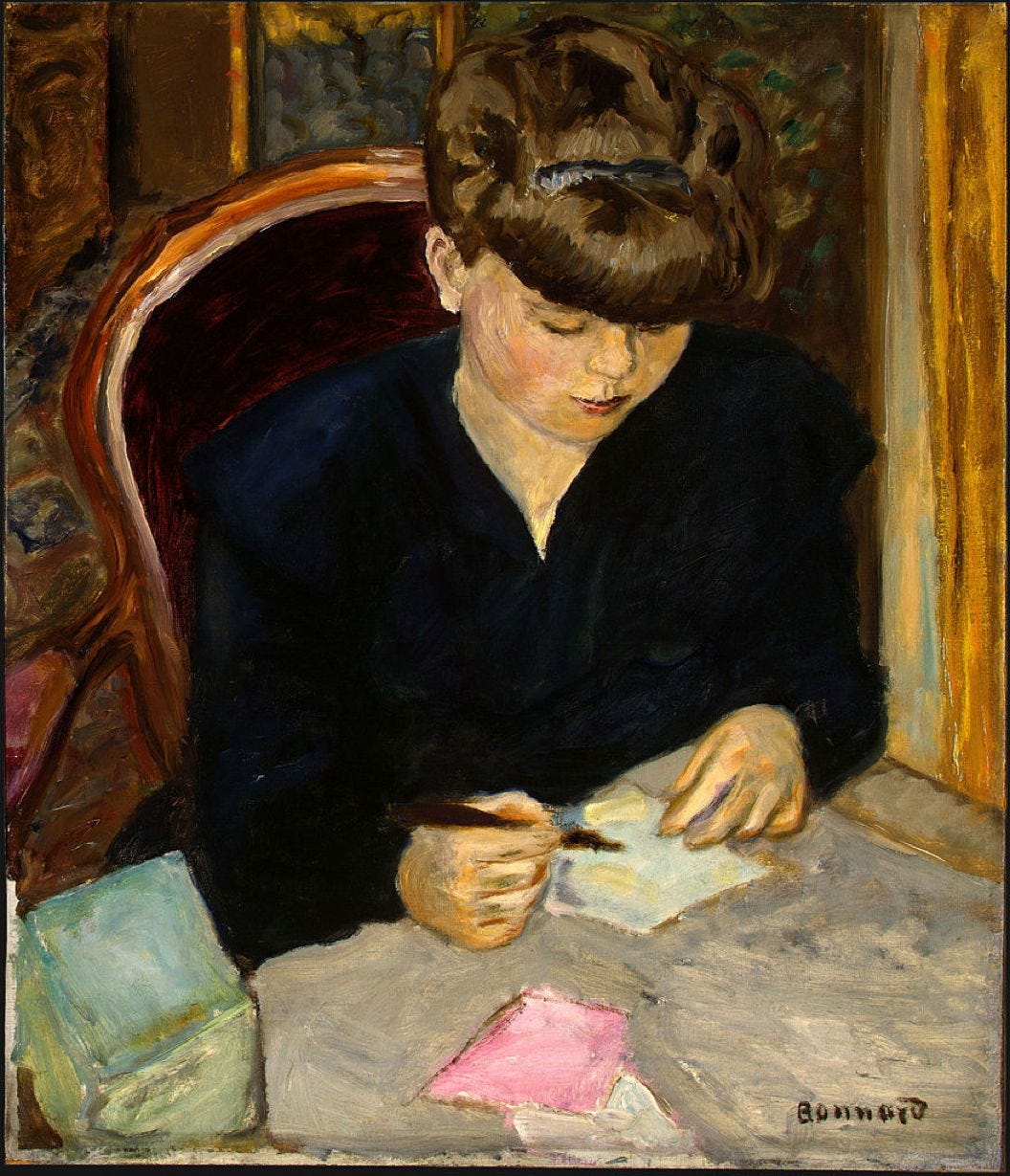

Page from the Diary of Frida Kahlo

Equally superficial is the idea that, because they are inherently personal documents, diaries must necessarily speak only truth. Lawrence Durrell was alive to this when he wrote in the Balthazar book of his superb Alexandria Quartet (1958):

‘A diary is the last place to go if you wish to seek the truth about a person. Nobody dares to make the final confession to themselves on paper: or at least, not about love.’

Simone de Beauvoir was equally distrustful of diary writers' honesty, choosing instead to focus on what is omitted as the greater source of truth:

‘What an odd thing a diary is: the things you omit are more important than those you put in.’

Simone de Beauvoir, The Woman Destroyed, 1967

Meanwhile, John Steinbeck is characteristically honest about his dishonesty. He's quoted as saying:

‘I have tried to keep diaries before but they didn’t work out because of the necessity to be honest.’

World of dreams, Laura Theresa Alma-Tadema, 1876

Julia Samuel, a psychotherapist and author of Grief Works (2017), discusses some of the advantages of diary keeping, and argues that it can have a positive impact on mental and physical health, telling BBC radio:

“writing a journal is as effective as talking therapies - it helps regulate emotions, anxieties and stress, it even improves our immune system”

No surprises there. Diary writing is by its nature contemplative, mindful, still. It helps us to pay attention to our life and, by reading back over what we have paid attention to, also helps us to better understand and grapple with our preoccupations in order to make peace with them. As compulsive diary writer Anaïs Nin says:

“In the journal I am at ease.”

The Letter, Pierre Bonnard, c 1906

At ease for the moment anyway. The story the next day might be a little different. I find myself feeling similarly to Jonathan Franzen when he writes in his 2006 memoir The Discomfort Zone that:

‘I could manufacture excruciating embarrassment in the privacy of my bedroom, simply by reading what I’d written in the journal the day before. Its pages faithfully mirrored my fraudulence and pomposity and immaturity.’

It's why I stick so rigidly to the diary-as-simple-list-of-events approach. Tony Benn is similarly self conscious of yesterday's musings, admitting:

‘something happens, you write it down, you re-read it, then realise that you were wrong’

Anyway, the eyelids are starting to drop and it’s looking as though it’s been another evening lost without having opened the page, another day vanished from the memory as though it had never been. Perhaps there'll be some black marks on white paper vouching for the existence of tomorrow.

Until then, in the immortal words of one last famous diary writer...

‘And so to bed.’

Ratty, Inga Moore, Illustration for Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows

Thanks for reading The Humanities Library ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

I've kept some sort of diary on and off for most of my life. I loved the quote about regretting the absences and only feeling 'master' for the periods you wrote, I recognise that feeling -- but it cuts the other way too, I have consciously stopped keeping a diary once or twice in certain periods that I actively did not want to remember. Recently I've been rereading a diary I kept daily for eight months when I was 6 and 7, but which stops either just before, or at the time of, a very frightening experience. The experience isn't mentioned in the diary, so it's not clear whether it stopped because of it, but I suspect so -- I think it was something I couldn't or didn't want to write down, but also couldn't honestly ignore. Funny to see these themes from your piece reflected even in such an early example of the genre.

This is lovely - and made me think about why I am also a (very sporadic) diary writer, when so many people grow out of it/don't see the point. I like Delacroix's Journals very much so glad you've highlighted those. And it's poignant that Woolf thought of her many volumes of diaries as 'a great mass for my memoir', material she would use later, but of course never did. But many of us are glad that her diaries exist in the format put together by Anne Olivier Bell in the 1970s, and completed in the Granta edition recently.