Just a short anthology of writing and art inspired by jazz, curated for fan’s of writing and art and jazz.

“Practically everything I know about writing, then, I learned from music… and mainly from jazz”

Haruki Murakami in a 2007 New York Times essay.

“Let my children have music! Let them hear live music. Not noise. My children! You do what you want with your own!”

Charles Mingus, from the liner notes of Let My Children Hear Music, 1972

Orpheus and the Musicians, James Lesesne Wells, 1982

“God has wrought many things out of oppression. He has endowed his creatures with the capacity to create-and from this capacity has flowed the sweet songs of sorrow and joy that have allowed man to cope with his environment and many different situations.

Jazz speaks for life. The Blues tell the story of life's difficulties, and if you think for a moment, you will realize that they take the hardest realities of life and put them into music, only to come out with some new hope or sense of triumph. This is triumphant music.

Modern Jazz has continued in this tradition, singing the songs of a more complicated urban existence. When life itself offers no order and meaning, the musician creates an order and meaning from the sounds of the earth which flow through his instrument.

It is no wonder that so much of the search for identity among American Negroes was championed by Jazz musicians. Long before the modern essayists and scholars wrote of racial identity as a problem for a multiracial world, musicians were returning to their roots to affirm that which was stirring within their souls. Much of the power of our Freedom Movement in the United States has come from this music. It has strengthened us with its sweet rhythms when courage began to fail. It has calmed us with its rich harmonies when spirits were down. And now, Jazz is exported to the world. For in the particular struggle of the Negro in America there is something akin to the universal struggle of modern man. Everybody has the Blues. Everybody longs for meaning. Everybody needs to love and be loved. Everybody needs to clap hands and be happy. Everybody longs for faith.

In music, especially this broad category called Jazz, there is a stepping stone towards all of these.

We must use time creatively.”

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Speech at 1964 Berlin Jazz Festival

Swing Landscape, Stuart Davis, 1938

“As much as he liked jazz, Oliveira could never get into the spirit of it like Ronald, whether it was good or bad, hot or cool, white or black, old or modern, Chicago or New Orleans, never jazz, never what was now Satchmo, Ronald and Babs, "So what's the use if you're gonna cut off my juice," and then the trumpet's flaming up, the yellow phallus breaking the air and having fun, coming forward and drawing back and towards the end three ascending notes, pure hypnotic gold, a perfect pause where all the swing of the world was beating in an intolerable instant, and then the super-sharp ejaculation slipping and falling like a rocket in the sexual night, Ronald's hand caressing Babs's neck and the scratching of the needle while the record kept on turning and the silence there was in all true music slowly unstuck itself from the walls, slithered out from underneath the couch, and opened up like lips or like cocoons.

"Ça alors," said Étienne.”

Julio Cortazar, Hopscotch, 1963

Empress of the Blues, Romare Bearden, 1974

“Thump, thump, thump, went his foot on the floor. / He played a few chords then he sang some more— / “I got the Weary Blues / And I can’t be satisfied. / Got the Weary Blues / And can’t be satisfied— / I ain’t happy no mo’ / And I wish that I had died.” / And far into the night he crooned that tune. / The stars went out and so did the moon. / The singer stopped playing and went to bed / While the Weary Blues echoed through his head. / He slept like a rock or a man that’s dead.”

Langston Hughes, The Weary Blues, 1926

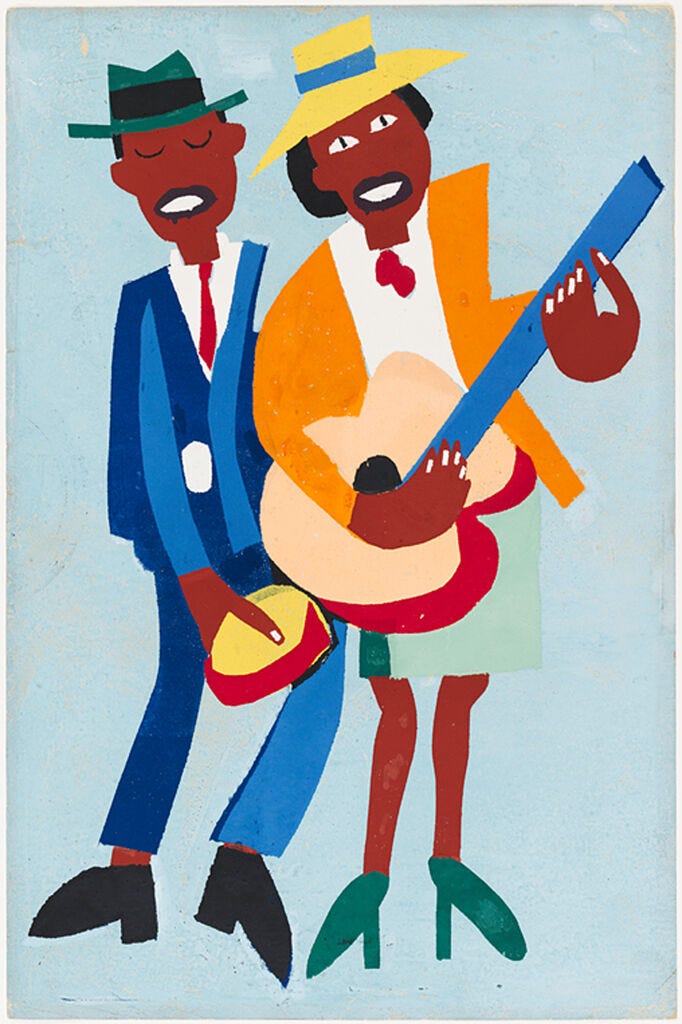

The Blind Singer, William Henry Johnson, 1945

“But there was a discipline, it was just that we didn't understand. We thought he was formless, but I think now he was tormented by order, what was outside it. He tore apart the plot - see his music was immediately on top of his own life. Echoing. As if, when he was playing he was lost and hunting for the right accidental notes. Listening to him was like talking to Coleman. You were both changing direction with every sentence, sometimes in the middle, using each other as a springboard through the dark. You were moving so fast it was unimportant to finish and clear everything. He would be describing something in 27 ways. There was pain and gentleness everything jammed into each number.”

Michael Ondaatje, Coming Through Slaughter, 1976

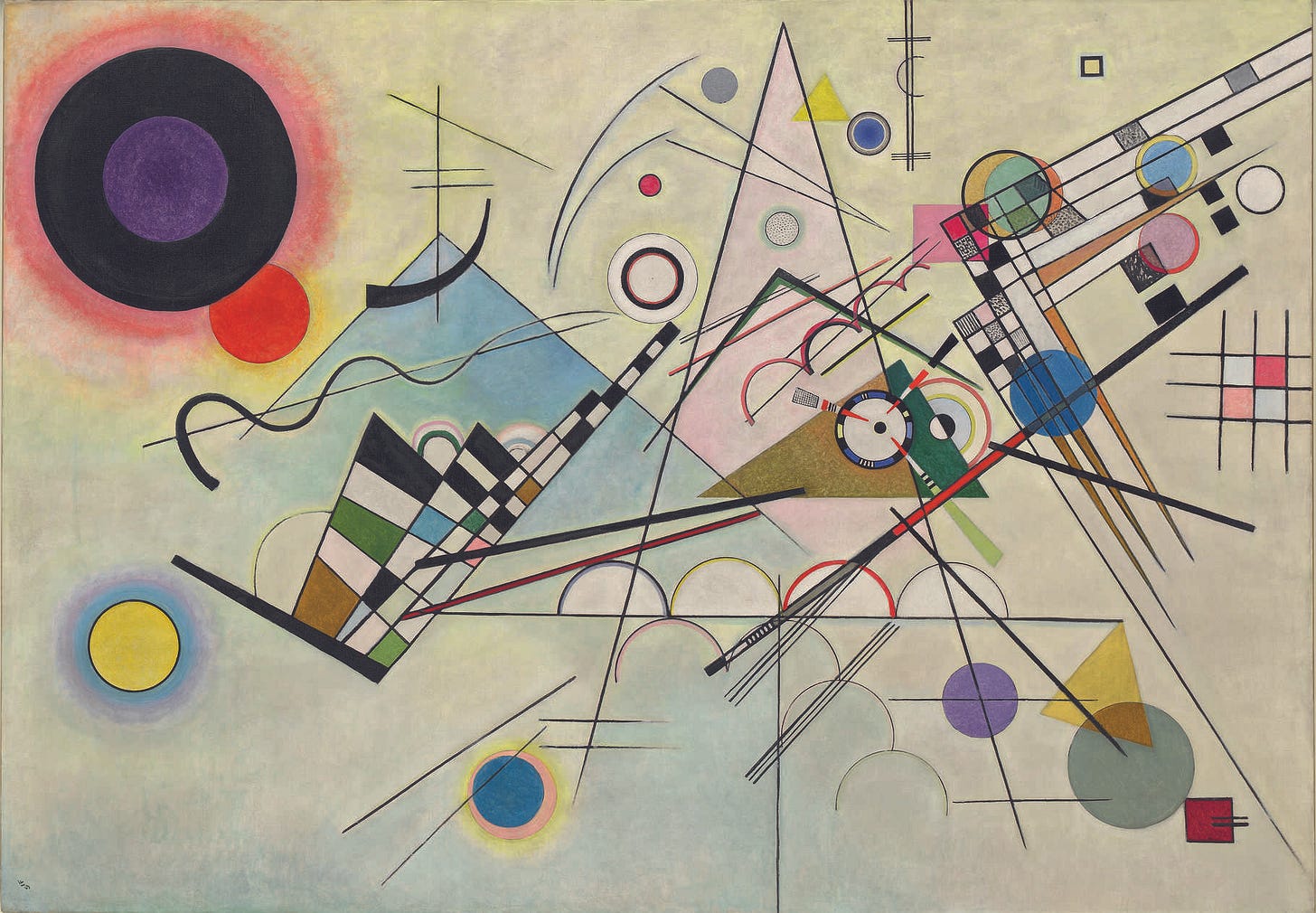

Composition 8, Wassily Kandinsky, 1923

“Jazz did a number of things to popular music as well as to metropolitan life. It sped up the tempo of things. Whether it was a cause, or the effect of a still more general cause, is here beside the point. Once the new musical spirit had come, it rapidly spread into daily-and nightly!-activities. It was not long before the old type of musical comedy began to appear outmoded. "Pep" was heard in the land. Once we had "ragged" words; now we "jazzed up" everything.”

Isidore Witmark & Isaac Goldberg, From Ragtime to Swingtime, 1939

“In back of the joint in a dark corridor […] scores of men and women stood against the wall drinking wine-spodiodi and spitting at the stars—wine and whiskey. The behatted tenorman was blowing at the peak of a wonderfully satisfactory free idea, a rising and falling riff that went from “EE-yah!” to a crazier “EE-de-lee-yah!” and blasted along to the rolling crash of butt-scarred drums hammered by a big brutal Negro with a bullneck who didn’t give a damn about anything but punishing his busted tubs, crash, rattle-ti-boom, crash.”

Jack Kerouac, On the Road, 1957

“If you find a tune and it’s got something to do with you, you don’t have to evolve anything. You just feel it, and when you sing it other people can feel something too.”

Billie Holiday, Lady Sings the Blues, 1956

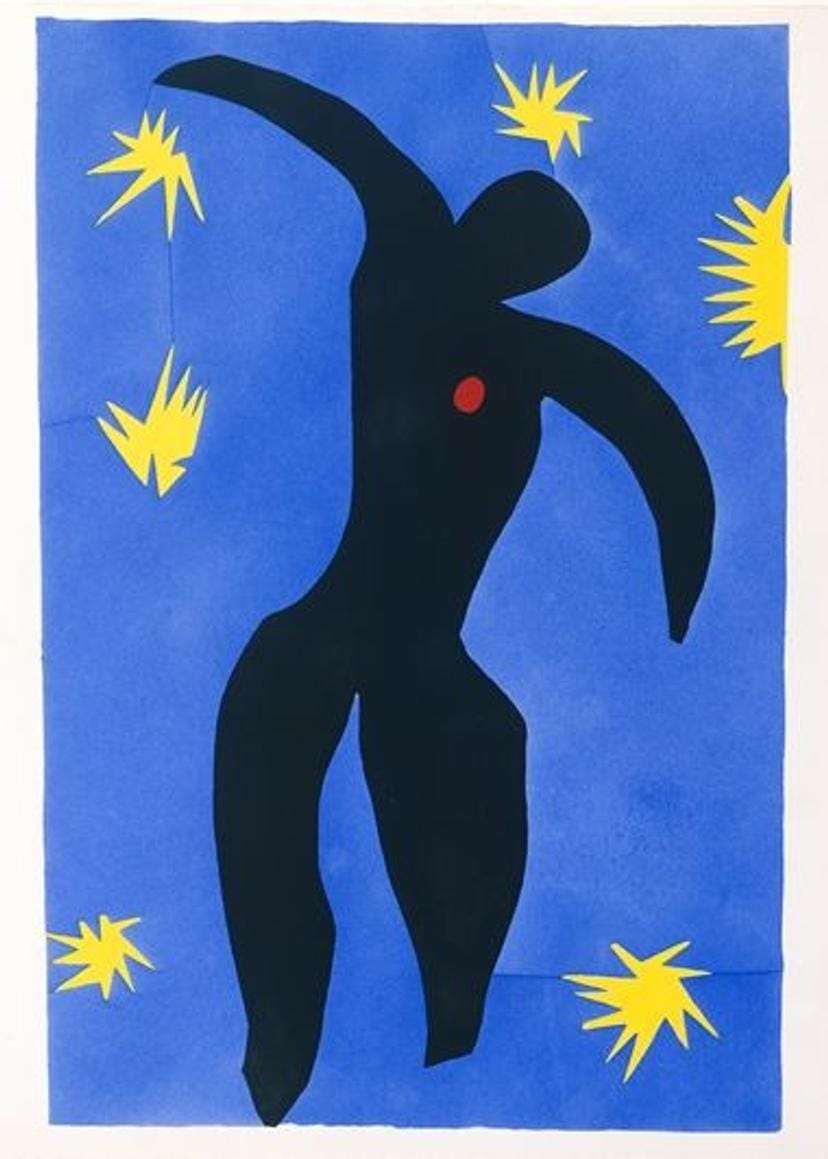

Icarus, plate VIII from the illustrated book "Jazz," Henri Matisse, 1947

“At twelve, I began listening to John Coltrane, Clifford Brown, Miles Davis, and Freddie Hubbard. Just by paying serious attention to these musicians every day, I came to realize that each musician opens a chamber in the very center of his being and expresses that center in the uniqueness of his sound. The sound of a master musi- cian is as personalized and distinct as the sound of a person's voice. After that basic realization, I focused on what they were communicating through music - pure truth, delivered with the intimacy of friends revealing some secret, sensitive detail about themselves. It takes courage and trust to share things. Many times the act of revelation brings someone closer to you. In learning about a person, you learn something about the world and about yourself, and if you can handle what you learn, you can get closer, much closer to them.

That's why, I came to understand, the scuffling jazzmen around my father were so self-assured. They didn't mind you knowing who they were. With Coltrane, of course, I was impressed with his virtuosity, his ability to run up and down his horn. Everyone who heard him was. But I noticed that the most meaningful phrases were almost never technically challenging. They were succinct phrases that would run right through you, the way profound nuggets from Shakespeare's plays can both cut through you and linger, all those words in Hamlet, but you remember "To be or not to be" or "to sleep perchance to dream." Something in those types of phrases reveals universal truth.”

Wynton Marsalis, Moving to Higher Ground, 2008

“Sonny's fingers filled the air with life, his life. But that life contained so many others. And Sonny went all the way back; he really began to make it his. It was no longer a lament. I seemed to hear with what burning he had made it his, with what burning we had yet to make it ours, how we could cease lamenting. Freedom lurked around us and I understood, at last, that he could help us to be free if we would listen, that he would never be free until we did.”

James Baldwin, Sonny's Blues, 1957

Otto Dix, Metropolis, 1928

“Lester's sound was soft and lazy but there was always an edge in it somewhere. Sounding like he was always about to cut loose, knowing he never would: that was where the tension came from. He played with the sax tilted off to one side and as he got deeper into his solo the horn moved a few degrees further from the vertical until he was playing it horizontally, like a flute. You never got the impression he was lifting it up; it was more like the horn was getting lighter and lighter, floating away from him and if that was what it wanted to do he wouldn't try to hold it down.”

Geoff Dyer, But Beautiful: A Book About Jazz, 1991

Lester Young

“In the first place maybe he shouldn't have got himself mixed up with negroes. It gave him a funny slant on things and he never got over it. It gave him a feeling for undisciplined expression, a hot, direct approach, a full-throated ease that never did him any final good in his later dealings with those of his race, those whom civilization has whipped into shape, those who can contain themselves and play what's written. But whether he should have or shouldn't have doesn't matter much now.”

Dorothy Baker, Young Man with a Horn, 1938

“In my room, I imagined the dance halls across America that my mother spoke of with such joy and reverence. She loved to talk about how people would work hard all week and then get their hair fixed either in somebody's kitchen or a beauty parlor. Hair was cut and mustaches were trimmed in the barber shop, where lies were told, predictions of personal success were made, and the blue stories of men and women were nearly acted out with emphasis on humor, irony, and the pathos of heartbreak that sometimes led to violent tragedy. The two sexes would meet when the women put on some version of a dress that had been copied out of a fashion magazine while the men wore suits that had been bought "on time."

Once they were ready, the young men and the young women would go to those places like the Elk's Ballroom and become something much closer to what they felt they should always be. The women were as beautiful as they could make themselves and the men got as close to handsome as possible. Both took to the wooden heaven of the dance floor, ready for anything that felt good and was good. Out there, under the lights or off in the corners, they would do some rug-cutting and some romantic leaning, getting very close as they gently hugged each other, either talking or listening to a line of "trash" as bands like Duke Ellington and his men created aural fantasy lands of grace and glamour”

Stanley Crouch, Considering Genius, 2006

“And the pitiful thing is that there are a few that do want to listen. And some of the musicians . . . we want to hear each other, what we have to say tonight, because we’ve learned the language. Some of us know it too well. Some of us know it only mechanically. But by listening to others who play it spiritually, soulfully, we can learn to speak a little less technically. . . . [Jazz] is another language, so much more wide in range and vivid, and warm and full and expressive of thoughts you are seldom able to convey.”

Charles Mingus

“When someone else was soloing he got up and did his dance... His dancing was a way of conducting, finding a way into the music. He had to get inside a piece, work himself into it like a drill biting into wood. Once he had buried himself in the song, knew it inside out, then he would play all around it, never inside it. His body was his instrument and the piano was just a means of getting the sound out of his body at the rate and in the quantities he wanted. He could do anything and it seemed right. He'd reach into his pocket for a handkerchief, grab it, and play with just that hand, holding the handkerchief, mopping up notes that have spilled from the keyboard, wipe his face while keeping the melody with the other hand as though playing the piano came as easy to him as blowing his nose.”

Geoff Dyer, But Beautiful: A Book About Jazz, 1991

“Ha! to the gray-haired matron in the final row. Ha! Miss Susie, Miss Susie Gresham, back there looking at that co-ed smiling at that he-ed-listen to me, the bungling bugler of words, imitating the trumpet and the trombone's timbre, playing thematic variations like a baritone horn. Hey! old connoisseur of voice sounds, of voices without messages, of newsless winds, listen to the vowel sounds and the crackling dentals, to the low harsh gutturals of empty anguish, now riding the curve of a preacher's rhythm I heard long ago in a Baptist church, stripped now of its imagery: No suns having hemorrhages, no moons weeping tears, no earthworms refusing the sacred flesh and dancing in the earth on Easter morn. Ha! singing achievement, Ha! booming success, intoning, Ha! acceptance, Ha! a river of wordsounds filled with drowned passions, floating, Ha! with wrecks of unachievable ambitions and stillborn revolts, sweeping their ears, Ha! ranged stiff before me, necks stretched forward with listening ears, Ha! a- spraying the ceiling and a-drumming the dark-stained after rafter, that seasoned crossarm of torturous timber mellowed in the kiln of a thousand voices; playing Ha! as upon a xylophone; words marching like the student band, up the campus and down again, blaring triumphant sounds empty of triumphs.”

Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man, 1952

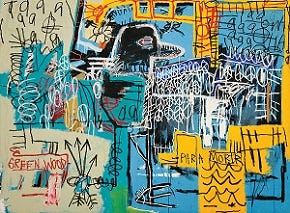

“Music is your own experience, your thoughts, your wisdom. If you don't live it, it won't come out of your horn.

They teach you there's a boundary line to music, but, man, there's no boundary line to art.

I lit my fire, I greased my skillet, and I cooked.”

Charlie Parker

Bird on Money, Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1981

I sometimes think of jazz as that mysterious delta where our individual tributaries meet, commingle, and surge forth together, something like a cultural river mouth where brackish waters carry both heartbreak and hope, tradition and rebellion, clarity and cacophony.

It feels bigger than a sound; it’s an undercurrent that tugs at our shared histories, especially in the ways it transmutes private, personal truths into communal revelations.

It’s no coincidence that so many of the voices above describe jazz as both highly personal and yet endlessly unifying, it’s an art form made of collisions, the place where we realize we need each other’s dissonances as much as the harmonies.

I enjoyed this post. Wish there were derivations stated for each quote, particularly the one from Charlie Parker.