Issue #8: Why Does High Society Sneer at the Wealthy Working Class?

Bourdieu, Calvino and Eccentric Home Design

This week I heard a very old, very Mancunian (it's the accent spoken by the people of Manchester, England, where I live) voice on the bus angrily proclaiming that Manchester wasn't the same anymore, it had “turned to sh**.” If you're “in town” (the city centre) you “never hear a Manc voice anymore. Everyone's from f****** London.”

It drew a smile, but also got me to thinking about what makes a city a city. Where do we locate that hard-to-define concept of a city's identity? Is it in the buildings, the history or, as my fellow passenger seemed to feel, the people? It's tempting to lean towards the latter, but how does this work alongside the anonymity that so often accompanies urban existence? And what happens when the population, as it so often is in cities, is very transient?

I don't think I've found any answers really - I'd love some reading recommendations to point me in the right direction - but what I do have is an extract from Calvino’s Invisible Cities that feels like it gives us something to work with.

I've also spent some time this week with Pierre Bordieu, who's concept of cultural capital has become huge in educational discourse in recent years, but in my experience is seldom really understood.

In the issue:

Pierre Bourdieu on social mobility #sociology

Georges Perec reimagines our living spaces #architecture

Italo Calvino's spider web city #literature

On insignificance with Cuno Amiet #art

The earliest not-quite-photographs of the Mediterranean #photography

As always, something to think about this week

Why Does High Society Sneer at the Wealthy Working Class? Pierre Bourdieu on Social Mobility #sociology

“An Oxford man! Like hell he is! He wears a pink suit.”

The concept of social class is a tangled little knot. What Tom Buchanan puts his finger on when he says the above of his rival in love, Jay Gatsby, is that acceptance into upper spheres of influence takes more than just money.

Gatsby is moneyed. He's made something of himself. But to the Buchanans, whose fortune stretches back generations, who have built up powerful and influential social connections, who hide their money behind a veneer of civility, he's just not 'one of us.' They're learning more than what can be gleaned from books in this place they call Oxford.

When it comes to explaining the myriad and complex forces that are at play when it comes to social mobility, we can do a lot worse than look to French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, whose work in the 1970s and 1980s sought to illuminate the many and subtle ways in which power is transferred and social order maintained across generations.

His ideas centred around the concept of capital, which was a term that he expanded beyond it's traditional definition as 'wealth or physical assets that can be used to generate income or profit.' For Bourdieu, capital meant more than just money, resources, human labour. If such things were all that mattered, Jay Gatsby's foothold on his ascent up the social ladder would be far less unsure, far less hindered by the slipperiness of characters like the detestable Tom.

For Bourdieu, there are four forms of ‘capital’ that contribute towards the advancement of social position and power. The first, of course, is money, which he never dismissed as an important influence. Bourdieu termed this economic capital, and it refers to the way in which the path to success can be greased with a little financial muscle (perhaps you could afford the luxury of an unpaid internship, or to bolster your CV with some impressive unpaid overseas volunteering). But, for Bourdieu, it was never about the money, or at least it was never about the money alone.

He also spoke of something called cultural capital. Cultural capital refers to the cultural awareness and aesthetic tastes that characterise discourse in the corridors of power and can therefore serve as ‘currency’ for people walking those corridors. It’s not enough to just make your fortune; if you are not au-fait with Shakespeare, fine art, Greek mythology and anything else that typically makes up the curriculum of the nation’s most exclusive schools, there’s a sense in which you will always be partly excluded from the ‘higher class.’

It isn't just knowledge, though. Cultural capital also refers to skills, competencies and specific dispositions that carry cultural weight (think here of the courteous, suave self-deprecation of the old Etonian, the effortless likeability of a Prince William, a Tom Hiddleston, a (I'm told) David Cameron, think of that assumption of superiority lent all the more weight for never having to be formally expressed). Also objects. Not so much gaudy expensive watches (or pink suits), but books, instruments, artworks. Those markers of a cultural elite that doesn't have to, has never had to, draw attention to itself.

There's also social capital. By this, Bourdieu means the networks and patterns of associations that allow some people in society to get a leg-up into a particular career. Remember that guy you met at university, the one on your undergraduate course who dossed around and was always 'on the lash?' The one who demonstrated no special intellectual ability but who, you noticed years later on Facebook, had worked his way onto the writing staff at the Guardian? The one whose success you find yourself just a little bit envious of until a mutual acquaintance points out that his Dad edits the Times? Familiar? Or something like it? That's social capital.

The last of Bourdieu's capitals is called symbolic capital. Here, we're referring to the prestige, honour, recognition or respect that a person can accumulate in a given field. I'll let this useful little diagram fill in any blanks:

The last thing to say about these capitals is that they are, of course, very closely tied together, and for those with the capital to spend, it becomes possible to 'purchase' new forms of capital, to 'translate' one form into another. Say your old university drinking buddy now heads up an investment firm and donates money to your political campaign. Hey, you've just turned social capital into economic capital. If you were to win that campaign, you might be said to have earned some symbolic capital out of the equation as well. Say, on the other hand, you've got plenty of economic capital in your pocket and you decide to use it to overpay for a de Stael for the drawing room. This time, you're converting your economic capital into cultural capital.

Its a tangled little knot, is social class. And if you're an alien looking down at the web of human connections and wondering how on earth the millionaire owner of a chain of car dealerships could be thought of as being in a lower social class than a poorly reimbursed university psychology lecturer, or how the privileged owner of a grand and extravagant West Egg mansion could have his entire life achievements undercut for the simple mistake of wearing the wrong kind of suit, Bourdieu is the man I'd point you towards to explain it all.

Do We Really Need Bedrooms, Bathrooms and Kitchens?The Eccentric Home Designs of Georges Perec #architecture

‘A bedroom is a room in which there is a bed.’

It's not the finest quotation from the history of French literature, but on the metric of accuracy, it's difficult to disagree with novelist, filmmaker, documentarist, and essayist Georges Perec. He goes on...

‘A dining room is a room in which there are a table and chairs, and often a sideboard; a sitting room is a room in which there are armchairs and a couch; a kitchen is a room in which there is a cooker and a water inlet’ etc. etc. He goes on at length because, like the rest of us, he's an enormous fan of a list.

He does have a point here though, which is that we have a tendency to organise our rooms according to their function. We use each space for a specific daily task or set of tasks, and each daily task or set of tasks is conducted in its specific designated space. We're not sleeping in the bathroom unless we've strayed very far from the life-plan.

However, he also points out that most rooms are basically the same in their general qualities; in his words, and I love this quote, they're ‘never anything more than a sort of cube.’ Again, I'm finding it hard to argue with the guy.

Yet despite the malleable quality of the spaces we live in, we all conform to almost the exact same living arrangement. He's painting a picture of human imagination here that is pretty uninspired, and I'm sure you're excited to see, as I was when first reading this essay in his 1974 book Species of Spaces and Other Pieces, what a creative genius such as he has planned as an alternative.

Well, for starters, how about an apartment based on the functioning of the senses, complete with gustatorium, auditory, seeery, smellery and feelery? No? Well can I interest you in one designed around heptadian rhythms, moving through a Mondayery (some sort of laundry room), a Tuesdayery (a drawing room because apparently our forbears were happy to receive visitors on a Tuesday), a Wednesdayery whose furniture would be plasticine (Wednesday, it seems, in Perec's world, is the day for the glorification of children) etc.

A seeery?

Sometimes it takes an unconventional genius to help us look at the familiar through a new lens. Sometimes, too, it helps us to appreciate that the status quo might just be alright as it is.

Extract of the Week #literature

A city is not it's buildings, it’s not really even the people who inhabit them. People come, people go; nobody is essential in a city. What really makes a city is the relationships among its ever changing inhabitants, which persist even after those inhabitants have moved on. At least that's what I think Italo Calvino is saying in this passage about Ersilia, his spider web metropolis from Invisible Cities, that great travelogue to places that don't exist.

In Ersilia, to establish the relationships that sustain the city’s life, the inhabitants stretch strings from the corners of the houses, white or black or gray or black-and-white according to whether they mark a relationship of blood, of trade, or authority, agency. When the strings become so numerous that you can no longer pass among them, the inhabitants leave: the houses are dismantled; only the strings and their supports remain. From a mountainside, camping with their household goods, Ersilia’s refugees look at the labyrinth of taut strings and poles that rise in the plain. That is the city of Ersilia still, and they are nothing.

They rebuild Ersilia elsewhere. They weave a similar pattern of strings which they would like to be more complex and at the same time more regular than the other. Then they abandon it and take themselves and their houses still farther away.

Thus, when travelling in the territory of Ersilia, you come upon the ruins of the abandoned cities, without the walls which do not last, without the bones of the dead which the wind rolls away: spiderwebs of intricate relationships seeking a form.

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities, 1972

Image of the Week #art

Snowy Landscape, Cuno Amiet, 1904

Credited with providing the link between traditional and modern art in his home country of Switzerland, Cuno Amiet was at his boldest with 1904’s Snowy Landscape.

What fails to come across through online reproduction is the sheer size of this thing. Measuring more than four square metres, the space Amiet gives over to subtle variations of white is vast. It’s practically the entire picture.

It’s almost as an afterthought that the eye is drawn to the figure of a skier in the centre of the frame, utterly engulfed by the environment around him.

The insignificance of human life against the might of mother nature has been a recurring theme in art forms of all kinds since the Romantics, but this feels like something different. Just look at that figure; it’s not terror, not awe, there's no notion of the sublime or any other kind of excessive display of emotion. Its just a man or a woman stubbornly going about their business despite the hostility of their environment.

As Robert Frost once famously said about life: ‘it goes on.’

The Collection | Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey Daguerreotypes #photography

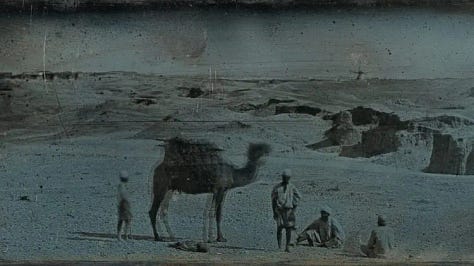

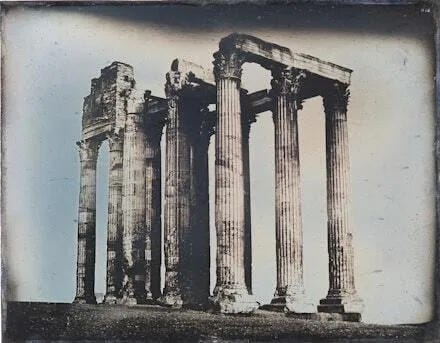

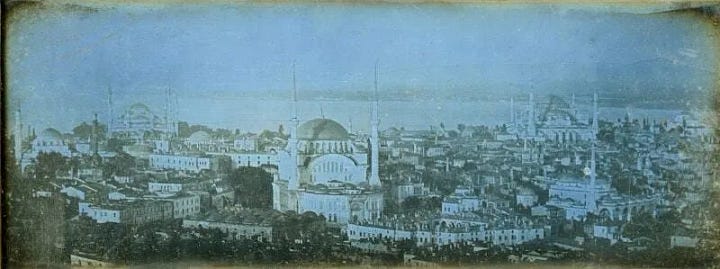

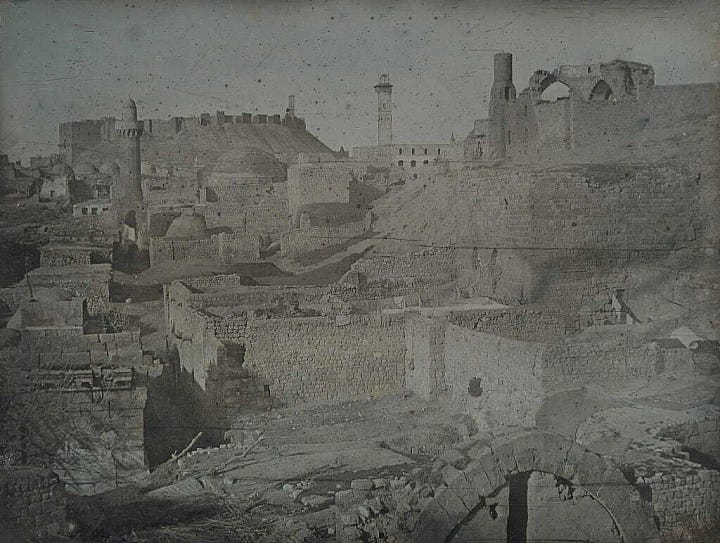

In 1842, a French photographer by the name Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey set out to explore the Mediterranean, spending three years working his way through Egypt, Turkey, Syria and Greece to name but a few of his stops. With him, he carried an extremely early forerunner of the modern camera.

The daguerreotype was a process for creating a detailed image onto sheets of copper plated with silver. It was a form of photography that was popular for barely a decade in the mid 19th century before faster and cheaper alternatives became available, but what it gave us, through de Prangey's work, was some of the earliest images of what were then largely unknown lands to those in the west.

The murky, colourless images work to emphasise the sense in which we're looking into a world shrouded in mystery.

Here are some of my favourites, featuring Aleppo, Constantinople, Athens, Rome and a desert near Alexandria.

The Examined Life

In a world where immigration routinely tops lists of the political issues people care about the most, could Calvino’s metaphor of the spider web do anything to shift conceptualisations of transient urban populations? Can a city be shaped by its human relationships? Would we want it to be? Can a city retain its identity amidst constant change and movement? Should we care if it doesn't?

If You Enjoyed It…

Go further by exploring this week's reading list:

Bourdieu, P. (1984) Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste

Perec, G. (1974) Species of Spaces and Other Pieces

Calvino, I. (1972) Invisible Cities

Pinson, S. C. (2019) Monumental Journey: The Daguerreotypes of Girault de Prangey

Or share with your people here:

That's your lot for another week. Don't miss the next issue where we’ll look for an answer to the question of why we can no longer talk across the political divide. I hope to see you then!

Fascinating article and the discourse re rooms, function, and categories was especially interesting. My mind connected that to Alain de Botton's call for reforming school and university courses around other kinds of themes like loss, lust, love, death, etc.

The discussion about rooms also made me think how stuck we are on function. I cant get away from seeing function in rooms organized by senses -- a room where we smell, a room where we see, seem hardly different than a room where we cook, or a room that is used on a monday... all function and function appears to be everywhere.

Bordieu is fascinating, I recall phrased that was something like structured structures structuring structures... the discussion of the kinds of capital was a very nice refresher for those of us who have read it directly and a splending introduction to those who have not. Thank you for the excellent post.

Great piece! I remember studying Bordieu 25 years ago at university. I was drawn in then and now I could cite many examples of how this capital has played out. Fascinating.