Issue #23: How to Grow Old With Dignity

Beauvoir, Oldenburg, Suffragettes and The Greatest Music Score Ever Designed

Welcome back to the Humanities Library, a space where timeless thinkers help us to navigate the enduring questions of human life. This week, aging, community, activism, beauty and one of my favourite opening lines in literature.

In the issue:

Simone de Beauvoir on Growing Old With Dignity #philosophy

Ray Oldenburg on the Value of Public Gathering #sociology

A Letter from the First Suffragette to be Imprisoned for the Vote #history

The Greatest Musical Score Ever Designed #music

The Genius of Donald Barthelme #literature

Simone de Beauvoir on Growing Old With Dignity #philosophy

Source: The Coming of Age by Simone de Beauvoir, 1970

At a glance: Old age brings with it a crisis of value in a world that worships productivity and youth, but we can overcome it with a radical reimagining of dignity.

"There is only one solution if old age is not to be an absurd parody of our former life, and that is to go on pursuing ends that give our existence a meaning — devotion to individuals, to groups or to causes, social, political, intellectual or creative work"

In comparison to studies on gender, race, sexuality, disability, religion and social class, age is something of a neglected category in the humanities.

I'm speculating here, but one reason for this neglect could be that older people just don't seem to fit into the category of marginalised or oppressed group in quite the same way as others.

To many in the younger generations, particularly in the West, the elderly are defined by their financial security and social conservatism. They seem safe, settled, and stubborn, owners of homes, holders of pensions, and guardians of yesterday’s prejudices.

In our age, which seems increasingly defined by intergenerational tension (if not outright conflict), they are seen not as victims of the system, but as its beneficiaries: voting for the status quo, clinging to property, and passing down values that feel out of step with the present.

But Simone de Beauvoir was one thinker who understood that old age is not a refuge from struggle, but another frontier of it, and in her 1970 work The Coming of Age she makes a case against the scandalous treatment of aging and the elderly in modern capitalist societies.

It remains one of the most urgent and underappreciated philosophical works of the 20th century.

The Coming of Age shares many thematic continuities with Beauvoir’s earlier and more celebrated work, The Second Sex. Just as she once argued that woman is constructed as the Other in a male-dominated society, she now positions the aged as similarly marginalised. Where she previously challenged the notion of gender as a mere biological fact, insisting instead on its social construction, she applies the same critical lens to old age, revealing it too as a category shaped by cultural attitudes and structural forces:

"old age can only be under-stood as a whole: it is not solely a biological, but also a cultural fact"

The aged, again similarly to women, are seen from without, treated as objects of knowledge to be viewed from an external standpoint. We even become aware of our own condition of aging not purely through internal experience, but through the stigmatising social judgement of others.

Anyone who has ever felt a jolt of surprise when a younger passenger offers them a seat on public transport, or has noticed the increasing proliferation of erectile dysfunction advertisements in their inbox, will understand exactly what she's getting at here.

Beauvoir draws a clear parallel between the social construction of femininity and that of old age, emphasising that both are positions defined by external attribution.

Social recognition, whether of a woman's allure or an elder's dignity, is not autonomously achieved, but bestowed by those in power: men in the case of women, and younger adults in the case of the aged.

"The most important fact to emphasize is that the status of the old man is never won but always granted. In The Second Sex I showed that, where women derive great standing from their magic powers, they owe it in fact to the men. This is equally true for the aged in relation to the adults."

This idea that status is conferred by the powerful is rooted in the logic of utility that underpins modern society. She's writing from a Marxist point of view here, claiming that:

"Society cares about the individual only in so far as he is profitable. The young know this. Their anxiety as they enter in upon social life matches the anguish of the old as they are excluded from it."

The elderly, therefore, who have outlived their functional utility in a capitalist world that values them only for their productivity, are not only marginalised but, for Beauvoir, completely dehumanised.

And she pulls no punches in her condemnation of France’s treatment of its elderly poor. She describes the policy of institutionalisation starkly and un-sentimentally, claiming that it:

“may be summed up in a few words—abandonment, segregation, decay, dementia, death”

She visited, as part of her research, several such state-sponsored facilities and was deeply affected by what she witnessed, writing that it:

“wrung [her] heart to see the utter listlessness bred by life in an institution."

It is little wonder, then, that Beauvoir detects in society a deeper aversion to old age than to death itself. Death, she argues, at least confers a kind of closure, transforming a life into a “destiny” and granting it an “absolute dimension.” Old age, by contrast, is for her the true antithesis of life, a prolonged social and existential exclusion.

There haven’t been many consolations so far, but it is at least gratifying that Beauvoir’s approach is rooted in empathy. She seeks not merely to describe old age from the outside, but to understand what it feels like for those actually living through it.

At the heart of her analysis is a profound disconnect she identifies in the experience of aging: the tension between the self as it is lived and the self as it is perceived.

Internally, many elderly individuals continue to feel a continuity of identity. Their ideals remain their ideals, their loved ones remain their loved ones, they still dance, they still follow their sports team, they're still repulsed by the flavour of a tomato, for example, and so on. They are the same person they have always been, yet society increasingly sees them as something Other.

Age, it would seem, is not a singular reality, but rather a sort of composite of biological, social, and psychological dimensions, each with its own timeline which rarely seem to align neatly.

Perhaps it would be a little reductive—but only a little—to suggest that it all reads like an intellectualised rendering of the old cliché that you're-only-as-old-as-you-feel.

Whilst her arguments about the experience of growing old reveal a profoundly pessimistic view of what, at this stage of her life, still lay ahead of her, it's pleasing to note that she herself did not, when old age eventually came, "sink into gloom" or "deaden" her "emotions" in the way that she was concerned we all did.

For Beauvoir, emotional intimacy and intellectual engagement remained as vital in old age as they had been in her youth. Even into the early 1980s, she remained a dynamic force in the French feminist movement, continued to write prolifically, and cultivated a profound and enduring bond with philosophy student Sylvie Le Bon, who she later adopted.

In many ways, she lived the advice she once offered:

"There is only one solution if old age is not to be an absurd parody of our former life, and that is to go on pursuing ends that give our existence a meaning — devotion to individuals, to groups or to causes, social, political, intellectual or creative work… In old age we should wish still to have passions strong enough to prevent us turning in on ourselves. One’s life has value so long as one attributes value to the life of others, by means of love, friendship, indignation, compassion."

Key takeaways:

Old age is not merely biological but socially constructed as a form of exile and marginalisation.

The elderly experience a disconnection between their inner self, or the self as it is lived, and outward societal perception, or the self as it is perceived.

To avoid losing a sense of meaning and purpose in old age, we must continue to pursue the relationships, intellectual pursuits and ideals that provide our sense of worth.

Ray Oldenburg on the Value of Public Gathering #sociology

Source: The Great Good Place by Ray Oldenburg, 1989

At a glance: Informal public gathering spaces like cafes, pubs, and barbershops are essential for community, democracy, and individual well-being, yet are increasingly endangered by modern life.

"How many Americans having “surfed” all the channels and, bored by it all, wouldn’t like to slip on a jacket and walk down to the corner and have a cold one with the neighbors? Ah, but we’ve made sure there’s nothing on the corner but another private residence"

Ray Oldenburg’s The Great Good Place (1989) is a sociological exploration of the importance of informal public gathering spaces in fostering healthy communities and personal well-being.

It's also a lamentation of the urban planning that has, for decades now, ensured that such spaces are in short supply, driving the average citizen of Western industrialised towns into an agonisingly isolated home-to-work-and-back-again daily shuttle.

Oldenburg is perhaps best known for coining the term “third places” to describe those social environments that exist between the private sphere of the home (the "first place") and the structured realm of work (the "second"). A third place, in his words, is:

"a generic designation for a great variety of public places that host the regular, voluntary, informal, and happily anticipated gatherings of individuals beyond the realms of home and work"

These include bars, cafés, pubs, barbershops, general stores, and other spaces where people can gather informally, converse, and build social connections.

At its glorious best—think of the Viennese coffee house, the Parisian café, or the good-old-fashioned-English-pub (tm)— the "third place" would play a critical role in building trust, encouraging democratic dialogue, and creating networks of mutual support for members of a community.

These were the everyday stages on which the idea of community would be enacted, where local people could gather within an inclusive atmosphere of comfort, neutrality and low profile, where they could expect to spontaneously bump into a host of regular faces, where—to borrow a phrase attached to perhaps the most famous "third place" of all—everybody knows your name.

Oldenburg laments that in modern society, such places are disappearing or have been commodified, with suburban sprawl, car culture, zoning laws, and consumerism all playing their part.

Where once people spent hours socialising freely, now interactions are often transactional, rushed, or virtual.

The result, Oldenburg claims, is a decline in civic engagement, increased social isolation, and a weakened sense of community that is negatively impacting our collective mental health. As he puts it:

"Social well-being and psychological health depend upon community. It is no coincidence that the "helping professions" became a major industry in the United States as suburban planning helped destroy local public life and the community support it once lent."

It's hard to argue that we've done anything but accelerate deeper into a life of isolation in the years since Oldenburg's work, and so his ideas offer a timely reminder that the community we crave doesn't just happen, it must be nurtured in shared spaces of spontaneous sociability and inclusivity.

Key takeaways:

Third places, like cafés, pubs, and barbershops, are essential for social connection, democracy, and mental well-being.

Modern life and urban planning have eroded these spaces, leading to isolation and weaker community ties.

Community doesn’t happen by accident; it must be nurtured in shared, inclusive spaces.

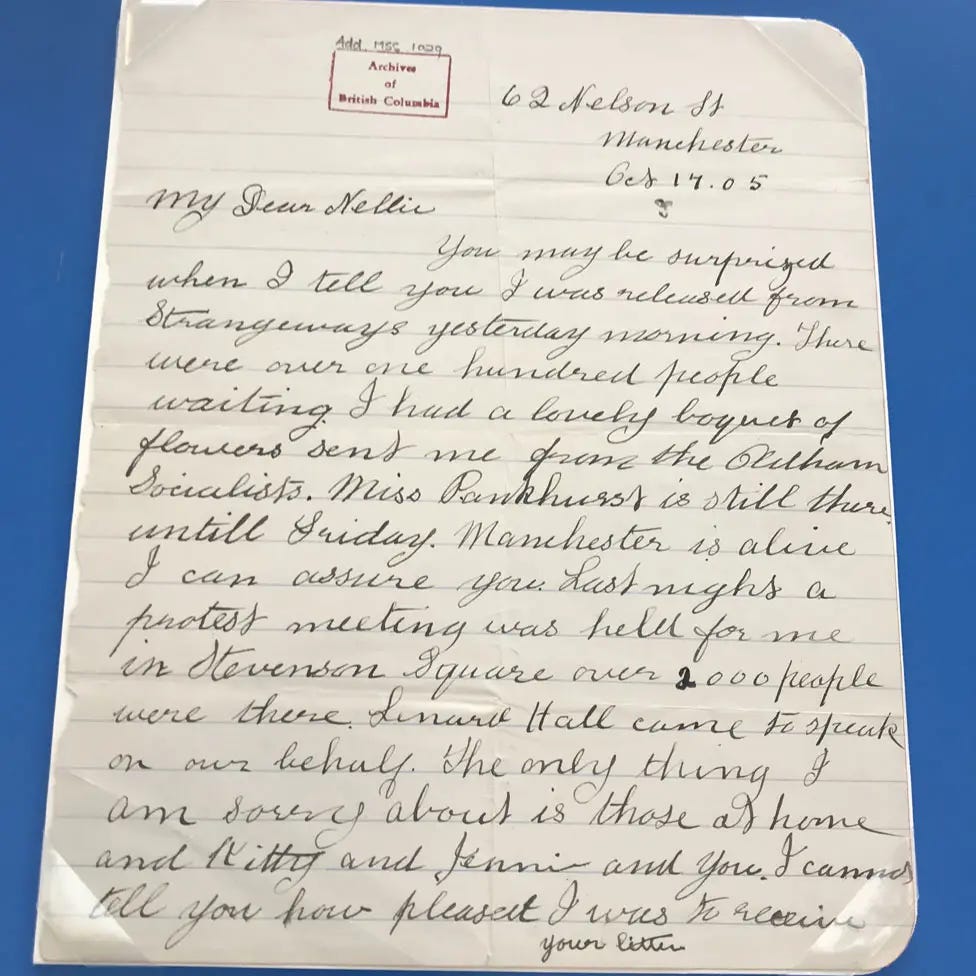

Extract of the Week: The First Suffragette to be Imprisoned for the Vote #history

The following is a letter from Annie Kenney, the first suffragette to be jailed in the campaign for the vote. Written to her sister the day after she was released from prison in Manchester in 1905, this represents the earliest account by a woman about what it's like to go to prison for the vote.

“My Dear Nellie

You may be surprised when I tell you I was released from Strangeways yesterday morning. There were over one hundred people waiting. I had a lovely boquet [sic] of flowers sent me from the Oldham Socialists. Miss Pankhurst is still there untill [sic] Friday. Manchester is alive I can assure you.

Last night a protest meeting was held for me in Stevenson Square over 2000 people were there Lenard Hall came to speak on our behalf the only thing I am sorry about is those at home and Kitty and Jennie and You, I cannot tell you how pleased I was to receive your letter and to find you so kind about it, I thought you would have been so indignant with me I cannot tell you anything here as there is so much to tell.

I am staying at Pankhurst [sic] for an indefinite time of course I am able to send money home every week. I sent it last week so that is alright. Alice is awfully angry about it but I don’t blame her, I’m living in hope to repay her for it all. She is working for me yet, they are removing to morrow. I can’t be there but Jessie is away from work for a day or so.

I will come and spend a weekend with you as soon as possible. I expect being at Middlesbourgh [sic] for a week or so, and I will write you from there

Ever Your Loving Sis

Nan.”

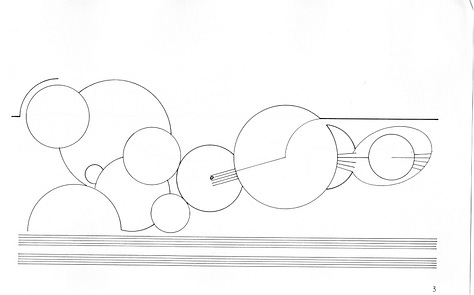

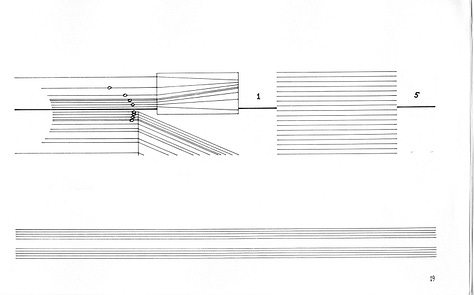

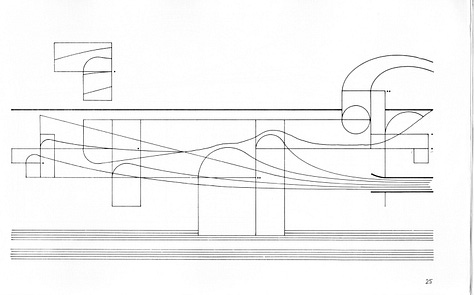

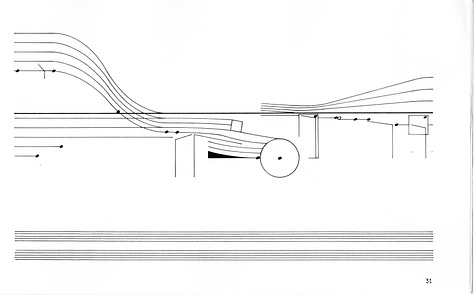

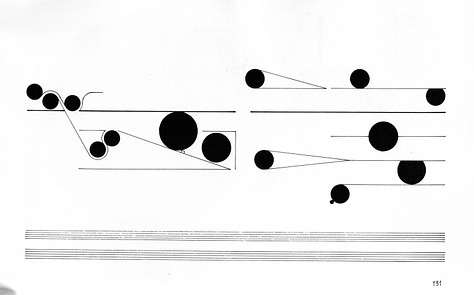

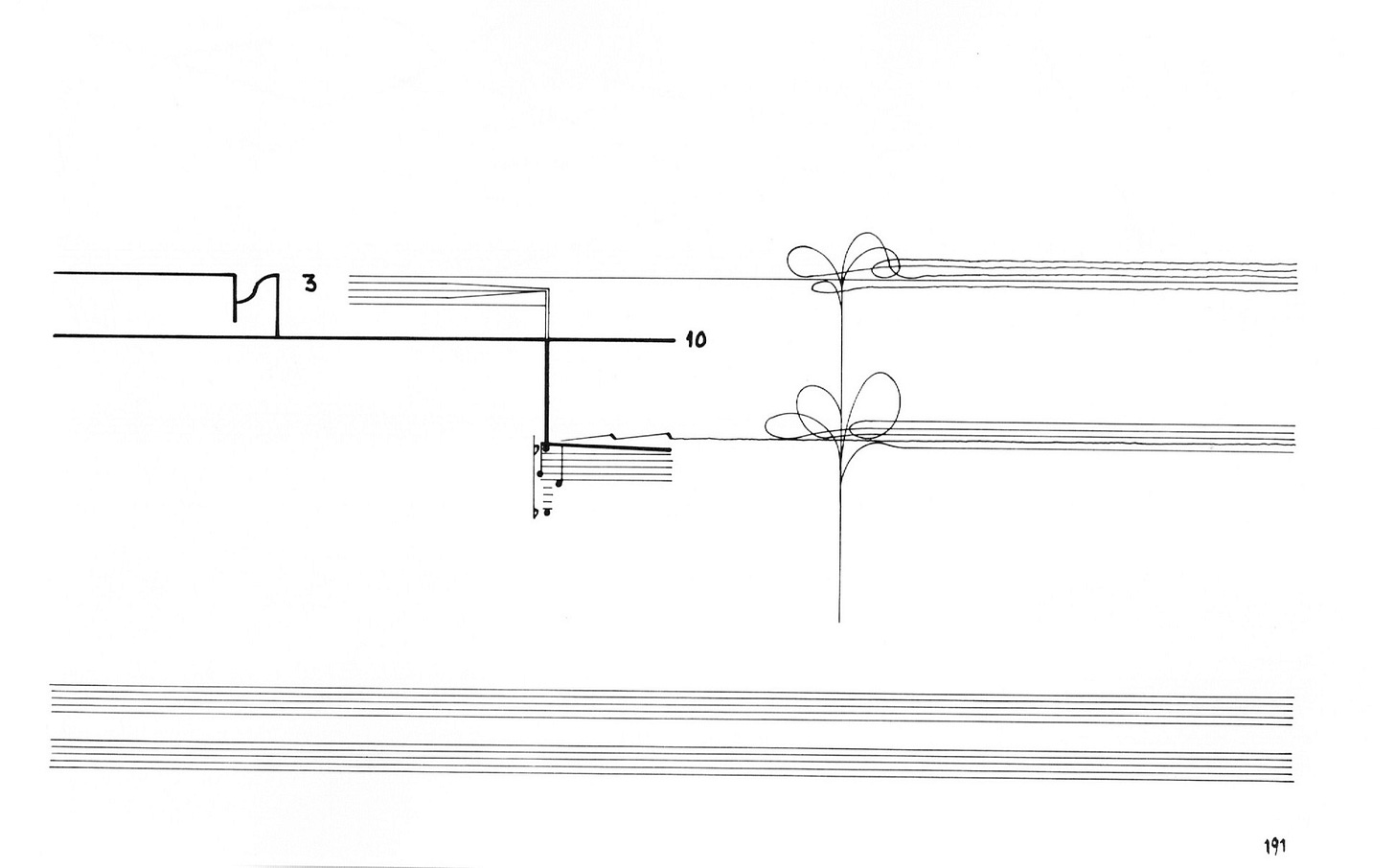

Image of the Week: The Greatest Musical Score Ever Designed #music

It's accepted wisdom today that our species is no longer capable of originality, but few would dare make that claim about Cornelius Cardew.

His Treatise (1963–67) is a monumental graphic music score consisting of 193 (!) pages of abstract shapes, lines, and symbols that defy conventional notation systems.

Occasionally, fragments that resemble staves or note-like figures emerge, but at no point does Cardew give instructions on how to interpret the symbols.

He described the piece as a "visual stimulus for musical ideas", rather than a directive. In his words:

"It is not the object of the composer to dictate an interpretation of the symbols but to encourage the interpreter to act on his own initiative."

And here's a beautiful interpretation by Kymatic Ensemble for you to lose yourself in for a while, and a gallery of a few more of the 193 pages of ‘music.’

The Collection: Donald Barthelme’s Genius #literature

Source: Sixty Stories by Donald Barthelme, 1981

Was there ever a better writer of opening lines than Donald Barthelme? Disorienting, enticing, compelling, hilarious. Here's a few of my favourites:

The Sandman

Dear Dr. Hodder,

I realize that it is probably wrong to write a letter to one's girlfriend's shrink but there are several things going on here that I think ought to be pointed out to you.

Will You Tell Me?

Hubert gave Charles and Irene a nice baby for Christmas. The baby was a boy and its name was Paul. Charles and Irene who had not had a baby for many years were delighted.

The Party

I went to a party and corrected a pronunciation. The man whose voice I had adjusted fell back into the kitchen. I praised a Bonnard. It was not a Bonnard. My new glasses, I explained...

Report

Our group is against the war. But the war goes on.

Views of My Father Weeping

An aristocrat was riding down the street in his carriage. He ran over my father.

After the ceremony I walked back to the city. I was trying to think of the reason my father had died. Then I remembered he was run over by a carriage.

On Angels

The death of God left the angels in a strange position.

I Bought a Little City

So I bought a little city (it was Galveston, Texas) and told everybody that nobody had to move, we were going to do just gradually, very relaxed, no big changes overnight. They were pleased and suspicious.

Thanks for reading! Until next time, have a wonderful week!

A fantastic piece. It terrifies me just how little support there is for the elderly - it exists on paper but is non existent in practice, something you don’t realise until you have to interact with the system. Covid showed just how dehumanising and dangerous the system is towards the elderly - and the lack of oversight of care homes is frightening. I am afraid of the assisted dying bill which whatever the theoretical arguments will be open to wide scale abuse - society is not protecting elderly people as it is.

I have been thinking much about aging and old age these days, and was happily surpised to find this piece of writing today. Will be looking in to de Beavoir's book asap. Do you have any other suggestions for reading on this theme? A note of my own: I have a feeling that old age is mostly considered as something negative, something to battle or overcome, rarely something to embrace or enjoy (and here I don't mean retirement), or even neutrally. I guess that in our western society youth is continuously so revered that this is the natural outcome. However, old age is a complex phenomenon, worthy of wider attention and contemplation.