Issue #2: How Do We Maintain Sanity in a World That Is Meaningless?

Cioran, Les Nabis and Pineapples

You know it's been a good week when you find yourself reading a book titled The Trouble with Being Born, but a reading session that began as self indulgent misery turned into something really quite special. What I offer you then, this week, is nothing less than a way out of your existential despair. Oh and pineapples.

In the issue:

Emil Cioran on existential despair #philosophy

Les Nabis, your new favourite art movement #art

Czesław Miłosz on ambition #literature

Pineapples on buildings, pineapples on plinths, pineapples on fenceposts #architecture

The less-celebrated side of our greatest renaissance man #history

As always, something to think about this week

How Do We Maintain Sanity in a World That Is Meaningless? Emil Cioran on Enduring the Human Condition #philosophy

We're all jealous of our pets aren't we? There's a simplicity to their existence. Theirs is a life uncomplicated with doubt, anxiety, or existential dread. Eat, sleep, survive, reproduce, die. For most of earth's organisms, this is the nature of their reality and they're content for it to be thus.

What's truly dreadful about the human condition is that we know too much to be content with eating, sleeping, surviving, reproducing and dying. We know that we are alive and, in a truly awful turn of events, we also know that we will die. Our greatest gift, our conscious intelligence, is also the curse that leaves us feeling short-changed by a life that offers mere existence.

For us to share the contentment of our household pet, we must first share their ignorance, and because we've come too far for that to be a genuine possibility for most of us, we instead perform a lifetime of cognitive contortions in the service of the upkeep of a great illusion - that our life has meaning, that our existence serves a purpose, that we're not just, in the words of that great writer of existential horror Thomas Ligotti, 'hunks of spoiling flesh on disintegrating bones.'

This week, I want to talk about Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran. His was not, and this isn't going to come as a surprise from the writer of such uplifting titles as ‘On the Heights of Despair,’ ‘Tears and Saints,’ and ‘The Trouble with Being Born,’ a sunny disposition. He can be lazily thrown in with Nietzsche and Schopenhauer into a vaguely philosophical-pessimistic, nihilist shaped bucket, and in a very real sense he belongs there. He did, after all, once write that ‘life not only has no meaning; it can never have one.'

But his reason for inclusion in these pages is not for his pessimism. He's far from the only mind to have lamented his being dragged into an absurd, meaningless world against his will - it's been a few years since True Detective's Rust Chole made the view mainstream. His belonging in the pages of a publication ostensibly claiming to be a celebration of life and human achievement stems from the direction he chooses to take all this nihilistic despair. He offers us, in his own idiosyncratic manner, a way out.

But before we get to that, let's examine the doors Cioran closes on us. For him, there are three ways that human beings tend to seek escape from the meaninglessness of their existence, and he's not having any of them.

First, we try to reason all the horrors away. The most obvious form such reasoning takes is religion: we're doing it all for some benevolent Daddy figure who'll be awaiting us in death with a pat on the head, an 'attaboy' and a promise of eternal pleasure. It certainly beats confrontation with Cioran’s 'truth.' But the reasoning Cioran dismisses also takes in philosophical ideas and systems - here was a philosopher who didn't believe in philosophy - as well as other forms of self help, political ideology and personal belief systems. All of it is intellectual dishonesty. All of it is a refusal to accept and stare down that uncomfortable reality of existence.

‘life not only has no meaning; it can never have one.’

Next comes distraction. It doesn't matter if it's Verdi at Teatro la Fenice or Sky Sports with some lagers, engagement with any form of entertainment is just a momentary diversion from the true emptiness of existence. It's not so much that Cioran railed against people having fun - sources agree that, despite his melancholy writings, he was good company in a Parisian bar - it's more that he felt it an inadequate solution to those feelings of dread that, like it or not, are going to get you in the end. Despite the best efforts of twitter algorithm writers, it's not yet possible to be plugged into an entertainment empire indefinitely.

The last escape hatch from existential turmoil is slightly more difficult to wrap your head around, but is maybe best summed up with the word 'acceptance.’ Think of an Eastern-philosophical-type-recognition that things are ultimately beyond our control and finding peace in that state of powerlessness. Cioran’s issue here was that he basically didn't believe that people were capable of true acceptance of the truth he was speaking. You're happy to be an accident of nature, existing in a state of meaningless suffering until the sweet release of death? Pull the other one, my enlightened friend.

So far, so many doors unceremoniously shut in our collective faces, but I promised he had answers, so here they are.

'When all the current reasons—moral, aesthetic, religious, social, and so on—no longer guide one’s life, how can one sustain life without succumbing to nothingness? Only by a connection with the absurd, by love of absolute uselessness.’

What does he mean by this? Essentially, I think his message is to embrace the world in all its meaningless absurdity. Denounce those rationalisations and distractions that turn you away from the horror of the human condition and instead stare into it and love the world for what it is and not for the sense of purpose it can offer you. It's bad enough that we're all here by some dreadful accident of nature, let's not add unnecessary pressure by convincing ourselves we're here for a reason and must therefore achieve something with our limited time, let's not inhibit our freedom of thought by delegating our moral reasoning to an organised religion that dictates to us the-meaning-of-it-all, let's not reduce our freedom to act by hooking ourselves to a paralysing ideological viewpoint that presents to us some big idea to fill the void.

It's all, ultimately, pointless, and is there not a way in which such a pessimistic view of the world is strangely intoxicating? Strangely liberating? Whilst everyone else seeks creative ways to avoid 'the Truth,’ is not the man who stares it in the face and laughs the most alive of us all?

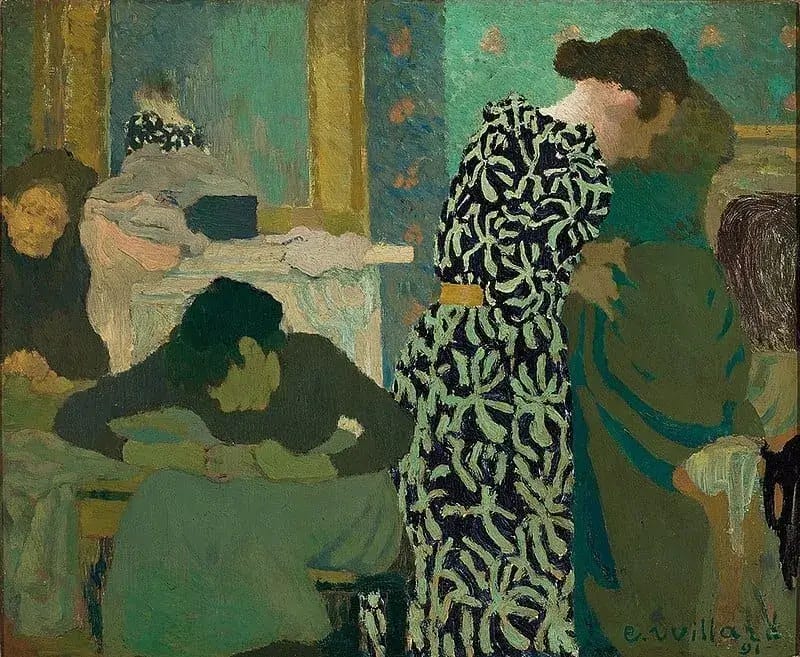

Les Nabis: In Celebration of the Decorative #art

How did the art world move from the impressionism of the late nineteenth century to the wildness of cubism, surrealism and abstraction in only a few decades? A key stepping stone has to be Les Nabis, meaning 'the prophets' in Hebrew, a movement that should be more well known than it is.

Le Talisman, Paul Sérusier, 1888

I always find myself drawn to artistic works that are 'just experimental enough.’ Not too Avant-Garde as to be impenetrable, but nor too mainstream as to be uninteresting. Scott Walker slapping a piece of meat in a recording studio, like he does on 2006’s The Drift, does little for me, likewise his early sixties commercial pop with the Walker Brothers. But somewhere in between is a sweet spot, the right blend of accessibility and experimentation, and I could listen to his late sixties albums for hours.

Les Nabis feel like that to me. Their work is about shape, pattern and above all colour, but they never quite reach pure abstraction. What presents itself first is the bold sensory experience, but there is a narrative that develops on closer inspection. For the most part, they're still painting people in places, they've just done away with the need to be naturalistic.

The Printed Dress by Édouard Vuillard (1891)

Theirs was an aesthetic, inspired by Japanese wood block prints, that foregrounded a new perspective: flatness. They also deviated from a lot of the art that followed in their desire to be decorative, which was never a pejorative in their eyes. The results are works that are less interested in accuracy and more in the sheer beauty of colour.

On the Beach of Trestrignel by Maurice Denis (1898)

If it isn't too reductive to say so, I can think of no movement better suited to brightening up an interior, especially if you make your home in a dull and grey climate like the UK.

At home with Marthe by Pierre Bonnard (1937-1943)

Extract of the Week #literature

This week, Polish poet and nobel prize winner Czesław Miłosz gives us a lovely way of conceptualising our ambition in this limited life of ours:

Fame

Not that I want to be a god or a hero. Just to change into a tree, grow for ages, not hurt anyone.

Image of the Week #architecture

Pineapples. They’re everywhere in UK architecture. As soon as you start noticing them, you won’t be able to stop.

Here’s one on St Paul’s Cathedral, London.

Here’s a pair on Lambeth Bridge.

There’s one settled on the highest ledge of the Binks building in my home city of Manchester.

These two guide you into a very fancy house.

This one is on a fencepost.

And, of course, our image of the week, the grand daddy of pineapple-related insanity in Dunmore, Scotland.

So, the obvious question - what is going on here?

Well, it turns out that pineapples have a long history as a decorative element in architecture, particularly during the Georgian and Victorian eras. We’d caught our first glimpse of the exotic fruit in 1493, but it wasn’t until the 1700s that it became an item of status and delicacy for the higher classes in Europe.

So desirable was the luxury item, that a host of a gathering could hope to display his wealth by renting one for his table centrepiece. In so doing, the pineapple gathered associations of wealth, status and hospitality to add to its existing exotic cred.

So, whilst that Dunmore pineapple speaks today of a nobleman losing touch with his sanity, once upon a time it told visitors to come in, because here be the party!

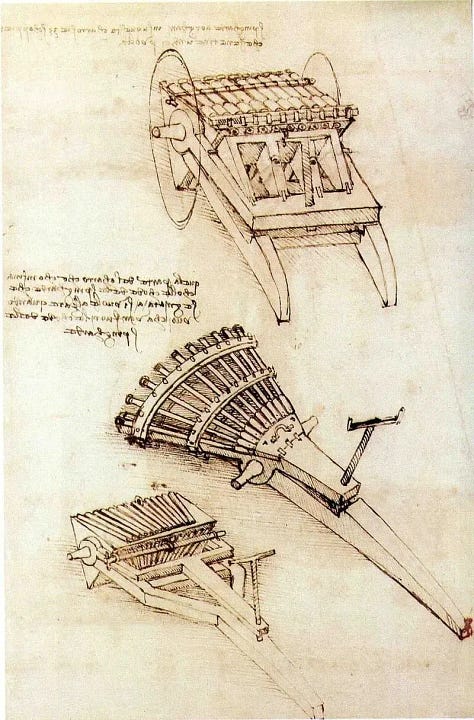

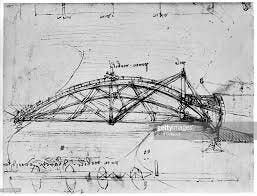

The Collection | Da Vinci's Killing Machines #history

It's such a shame, I think, that the forces of the market direct some of the greatest minds of our generation to the damaging task of monetising our attention for the financial benefit of tech companies. But it was ever thus.

We know him for the Mona Lisa, The Last Supper and for being the archetypal renaissance man, but the lesser appreciated side of Leonardo da Vinci was his penchant for turning his ingenuity to weapons design. The Italy of his time was characterised by fighting between city states, and the Sforza family of Milan would deploy his mind to the task of gaining that edge in warfare. This week, then, we look at his top five designs for ways mankind can kill each other with greater efficiency.

5. Da Vinci saw that cannons were taking a long time to reload, and solved the problem with the 33 barrelled organ, a forerunner of the modern machine gun.

4. Solving the twin issues of load time and mobility, da Vinci's triple barrel cannon was both multi barrel and lightweight enough to be portable. Excellent for scurrying around the battlefield.

3. Da Vinci's revolving bridge was designed to allow soldiers to cross rivers quickly before easily packing up for reuse elsewhere. Not just an innovation of warfare, then, but also an early example of flat pack design.

2. The precursor to the modern tank, da Vinci's armoured car was powered by eight men inside the tank turning cranks under the cover of a protective plate.

1. 27 yards across, da Vinci's giant crossbow was so large as to be almost unusable and was designed purely for the purposes of intimidation. I didn't say all the ideas were good ones!

The Examined Life

Cioran talks about entertainment as a distraction from the emptiness of existence. In this context, what role does art play in our lives? What role should it play? What to make of the idea, proposed by the artists of the Nabis movement, that art should be decorative? If all we're doing is avoiding ‘the Truth,’ can there be true distinction between ‘low’ and ‘high’ culture, between the value of the entertainment offered by Teatro la Fenice and that offered by Sky Sports? I'd love to hear your thoughts!

If You Enjoyed It…

Go further by exploring this week's reading list:

Cioran, E. (1973) The Trouble with Being Born

Kostenevitch, A. (2014) The Nabis

Miłosz, C. (2001) New and Collected Poems 1931-2001

Laurenza, D. (2006) Leonardo's Machines

Or share with your people here:

I think we'll leave it there for this week. Join me next time for adolescent angst and prominent jawlines. With a teaser like that, I'll confidently say “see you then.”

Thank you for your awsome article, specially for Les Nabis and Cioran.

A very interesting article, thank you. I remember discovering Cioran after watching the first season of True Detective. I was immersed in it then, searching for everything related to the series. Now, from a more detached perspective, his philosophy isn't as close to me anymore, but much of it still resonates with my worldview.