Issue #17: Can We Find Lasting Truth in the Dark Visions of a Medieval Nun?

Hildegard, Spengler and Some Nasty Little Water Spirits

When I started this thing however many months ago, part of my thinking (aside from the fame and glory) was that setting myself a schedule to post by would offer me the little nudge I so often need to actually turn off the telly and actually learn something from an actual book.

And it's working, because, despite having admired her music and been intrigued by her as an historical figure for years, it's only been in the last fortnight that I've made it through some of Hildegard von Bingen's actual writing. It's quite an experience, and I'll try to summarise just a bit of it below. It's got a human creature with rabbit ears and a worm's body, so there's your teaser for you.

But my favourite discovery of the week concerns Michelangelo and his Sistine Chapel. I'm decorating at the moment, and as I attempt to paint my own ceiling—dribbling paint over my face like the hapless amateur I am—I couldn’t help but wonder if the greatest ceiling painter of all time suffered the same indignities. So, after a long day of decorating, I took to researching his experience. To my immense satisfaction, I came across a letter he wrote midway through his four-year ordeal, where he lamented, in spectacular fashion, the very same struggle. It may even have given me the motivation to do the second coat next weekend.

As always, I'm incredibly grateful that you're here and would be even more so if you helped me to connect with new readers by giving this a share.

In the issue:

A twisted morality play from the mind of a brilliant medieval mystic #theology #literature

A struggle between creatives and pragmatists for the soul of society #sociology #history

Michaelangelo reveals he was human after all #art

A Tibetan death ritual defined by humility, generosity, and reverence for nature #anthropology

The creatures lurking beneath the water in mythologies around the world #literature #mythology

Can We Find Lasting Truth in the Dark Visions of a Medieval Nun? Hildegard von Bingen Personifies Human Vice #theology #literature

In a 12th century European society that generally preferred its women silent and obedient, one woman - Hildegard von Bingen - managed to carve out a space for herself.

That's putting it mildly, to be honest. What she really did was carve out several spaces for herself - abbess, writer, composer, scientist, mystic, theologian, healer, linguist, visionary, occasional inventor of secret languages.

She wrote books on medicine, studied the natural world, composed music that still gets performed today, and engaged in fiery theological debates with some of the most powerful men of her time. She's the kind of historical figure whose works you could easily spend a lifetime absorbing yourself in.

Illumination from Hildegard's Scivias (1151)

But let's allow her some space to describe herself in her own words, because, let me tell you, she'll do it quite effectively:

'I am the fiery life of the essence of God; I am the flame above the beauty in the fields; I shine in the waters; I burn in the sun, the moon, and the stars. And with the airy wind, I quicken all things vitally by an unseen, all-sustaining life.'

Stick that one above your mirror for your morning mantras.

Hildegard, and you're perhaps already picking up on this, was wired a little differently. From childhood, she claimed to have experienced visions, which she would later describe in striking, apocalyptic detail. These were not mere dreams or fleeting spiritual impressions; they were full-scale, Technicolor experiences, rich with symbolism and divine pronouncements.

And she didn't keep them to herself. She structured her visions into elaborate theological works, and presented them, with the backing of the church, as direct messages from God.

To read Hildegard’s visions is to step into a mind utterly convinced of its divine calling. Whether one sees her as a mystic or a masterful theologian, there is no denying the power of her imagery. Her world is one of stark moral clarity, where human folly is grotesque and salvation a hard-won battle. And in her writings, we see not just the medieval Church laid bare, but something more universal: the eternal human struggle between fleeting pleasure and lasting truth.

One of her most striking visions, titled The Seven Vices and Virtues, recorded in The Book of Life's Merits, is a kind of medieval fever dream of strange creatures, stern warnings, and poetic rebukes. It’s full of hybrid figures—part-human, part-animal—who embody various moral and spiritual failings, only to be firmly chastised by a celestial voice from a storm-cloud. If Dante’s Inferno had a slightly more mystical, medieval-psychedelic cousin, this might be it.

Fabulous creature from 'The Visions of Hildegard von Bingen'

The first figure, a dark-skinned man clinging to a flourishing tree, boasts of his power and worldly pleasures, saying, “I hold all the kingdoms of the world with all their flowers and adornments.” But as he speaks, the tree withers and he falls into darkness. The divine response is swift: he is a fool, chasing fleeting joys while blind to eternal life - "You live for the moment, then dry up like hay!"

And thus the pattern of the little drama is established. I suppose we could label this first pairing of vice and virtue something like love of the world vs heavenly love. And it all continues in the same vain.

Next comes a dog-like figure, eager for lightheartedness, dismissing the weight of mortality and arguing instead that we should 'be happy' whilst we can (I'm feeling a strong urge for some authorial intrusion here just to say that both of these terrible 'vices' so far - love for the world and happiness - are pretty much my life goals, but if Hildegard demands more from me then who am I to argue?) Again, this figure is scorned as a creature of empty words and reckless abandon -"You are like the wind blowing about in the squalid manners of playful men, but in your fickleness you are like the worms digging up the ground." Ouch. The heavenly voice of virtue here is discipline.

A third figure, a half-man with bear paws and a gryphon’s claws, champions joy and merriment. He says "It is better to be playful than sad. Play is not wickedness! Do not all who know God rejoice and sing?" Yet again he is condemned as an idolater, driven by whim rather than divine truth. He is superficiality and is scolded by the divine voice of shame.

It's not been much fun so far. The next one though is my favourite, and where I can really start to get on board with Hildegard's wonderfully austere and disciplinarian brand of chastisement. This figure is 'like a dense cloud of smoke in the shape of a man' and he declares "I have designed nothing and created nothing. So why should I labour for any good cause? Why tear myself to pieces? I will do no such thing! I will concern myself with people only if they profit me." He is an embodiment of indifference, who refuses to toil or care for others. His only concern is self-preservation. But even the stones and plants serve a purpose, the divine voice declares, while he is nothing but bitter smoke.

At this point in the text I'm really still here for the mad visions, and the next one is a corker. 'The fifth figure appeared to have a human head, except that his left ear was like the ear of a hare and so big that it covered the whole head. The rest of his body resembled the body of a worm, a boneless creature wound up in its lair like an infant wrapped in cloths.' This horrible figure seeks only to avoid conflict. It's the latest in a series of so-called virtues that, in the hands of Hildegard, are exposed as cowardice. This time, seeking peace, or to avoid hurting people, is chastised by divine victory for it's dishonesty.

A monstrous scorpion-mouthed creature follows, tangled in the spokes of a wheel, spitting fire and vengeance. His belief in retribution is met with scorn: true power lies not in anger but in gentle, life-giving patience.

The final mini-drama in the series is another example of Hildegard in that party-pooper role she so effectively embodies. The seventh figure, part man part goat, naked, asks "why should it matter if there is pleasure in my flesh?" The divine voice, desire for God, dismisses him as blind and foolish, mistaking fleeting gratification for true fulfillment.

This is the point where I usually break off from the text with a line or two about what we can take from the reading for the enhancement of our own lives, but there's just so much here in what is only a few pages of drama. What we've got here is effectively a medieval morality play, a warning wrapped in surreal, unforgettable imagery, and to be honest it's the imagery - figures with hare’s ears, scorpion mouths, and ape hands, all embodying different aspects of sin, each justifying themselves, each rebuked by the voice of divine wisdom - that will stay with me the longest.

At their core, Hildegard’s writings are about humanity’s constant struggle between earthly indulgence and eternal wisdom. And while the stakes in her visions are high—eternal damnation is never far away—there’s an undeniable energy to them, a creativity that makes them compelling even in a modern society that would have little time for the rigidly moralising tone.

Whether you see her as a divine visionary or, like me, just a fascinatingly interesting medieval mind, there’s no denying one thing: Hildegard knew how to tell a story.

What Happens When a Culture Stops Dreaming? Oswald Spengler on the Eternal Struggle Between Artists and Engineers #sociology #history

For Hildegard von Bingen, the world was not divided between art and science, spirit and structure. Everything—melody, medicine, theology—was part of a single, shimmering whole.

Her example got me thinking this week about Oswald Spengler, a man who would - if you fast-forward several centuries - draw up battle lines between two types of personality that Hildegard seems effortlessly to weave into one.

Spengler, if you haven’t read him, is one of those thinkers who deals in grand narratives, the kind that make the world feel at once inevitable and already lost. He doesn’t argue so much as pronounce, and when he divides humanity, he does so with the air of a man announcing a cosmic law.

On the one side, you've got the materialists. These are the engineers, the administrators, the men (because they usually are) of steel and circuits. The kinds of people who shape the world, whether by force or by function. The kinds of men, as I imagine them, who find sufficient nourishment for the human soul in a TED Talk about maximising efficiency.

On the other side, you've got what Spengler calls the aesthetes. This is where you'll find your poets, your painters, your mystics. People who dwell in the realm of beauty in the face of an economic system that steadfastly refuses to reward such frivololity and imprudence.

But this isn’t just a difference in temperament. For Spengler, it’s a civilizational fault line, the axis on which history turns.

When a culture is young, it dreams. It builds cathedrals, not factories; writes epics, not instruction manuals. The aesthetes are in charge, their vision pulling the whole thing forward.

But as time moves on, as the dream ossifies into routine, the materialists take over. What was once organic becomes mechanical. The age of poetry gives way to the age of the ledger, the workshop, the assembly line. The dreamers have their moment, and then the builders move in to standardise what they left behind.

And so it goes, until the whole thing exhausts itself.

It's a model of history (let's be honest here, a pseudo scientific model of history) that treats human culture as a biological entity with a predictable lifespan during which it moves through predictable phases towards a predictable decline.

That's unless (let's go there and address Spengler's political conclusions alongside his historical ones) you find a strong-man leader, of course, who can straddle the lines between the two personality 'types', blending the creativity of the aesthete with the realism of the materialist. This is the point at which things become a little tricky, to say the least.

Spengler was no democrat. In his later years, he leaned toward a vision of authoritarian rule as the only realistic option for a world in decline - an idea that, predictably, made him a favorite of certain right-wing movements, though even the Nazis, for all their interest in him, found his pessimism inconvenient.

Nevertheless, his view that history is shaped by great men rather than collective struggle and his reverence for the “strong hand” of leadership places him firmly in a reactionary tradition that should be dismissed out of hand.

And yet, for all his right-wing leanings, there’s something in Spengler’s framework that remains compelling. His distinction between the world of dreamers and the world of builders, between the early fire of artistic creation and the later march of industrial routine, still feels relevant, if only as a way of recognising the ongoing tension between these forces. At the very least, it gives us the language to name them, to see where the balance has tipped, and perhaps, if we’re lucky, to begin redressing it.

Extract of the Week #art

A tonic this week, for those of you (aesthetes here, rather than materialists) who have ever found yourself with your head on the desk over a creative project. In the letter that follows, Michelangelo writes to Giovanni da Pistoia of his struggles during the painting of the Sistine Chapel, proving that even the giants of art history still wrestle with doubt, exhaustion, and the creeping suspicion that they might be doing it all wrong.

1509

‘I've already grown a goiter from this torture, hunched up here like a cat in Lombardy (or anywhere else where the stagnant water's poison). My stomach's squashed under my chin, my beard's pointing at heaven, my brain's crushed in a casket, my breast twists like a harpy's. My brush, above me all the time, dribbles paint so my face makes a fine floor for droppings!

My haunches are grinding into my guts, my poor ass strains to work as a counterweight, every gesture I make is blind and aimless. My skin hangs loose below me, my spine's all knotted from folding over itself. I'm bent taut as a Syrian bow.

Because I'm stuck like this, my thoughts are crazy, perfidious tripe: anyone shoots badly through a crooked blowpipe.

My painting is dead. Defend it for me, Giovanni, protect my honor. I am not in the right place—I am not a painter.’

Worth it, in the end

Image of the Week #anthropology

Dignity in death is a cultural construct. Western traditions tend to emphasise preservation—sealed caskets, elaborate tombstones, a sense of permanence, but for Tibetans, true dignity comes not from resisting nature, but from embracing it.

In a traditional Tibetan sky burial, there is no coffin, no grave, no fire to turn flesh to ash. Instead, the body is laid bare on a mountaintop, exposed to the wind and the waiting beaks of vultures.

To an outsider, this might seem brutal, even unsettling. But to those who practice it, it is an act of humility, generosity, and reverence for nature—core values deeply embedded in Tibetan society.

Known as jhator, or "giving alms to the birds," this ritual stems from the belief that once a person has died, their body is an empty vessel. The consciousness has moved on; what remains is no longer needed.

In offering it to scavenging birds, Tibetans see not loss, but a final opportunity to give back—to sustain life even in death.

The Collection #literature #mythology

I'm afraid I have more death for you now. Not death rituals in the sky but death warnings from the deep, which is a symmetry so satisfying it gives the impression that it was all planned out that way.

It wasn’t. What happened was that I stumbled, quite by accident, upon the kappa—mischievous, turtle-like goblins of Japanese folklore, known for luring unsuspecting children to their doom beneath the water’s surface. And as I read, a distant memory stirred of another kind of river demon. Not a turtle, but a horse. Not Japanese, but Scottish. And while I grasped at the memory I found myself pulling at a thread that unravelled further than I expected.

It turns out, cultures all around the world have for generations spun myths about creatures lurking beneath the surface. These stories serve as warnings—cautionary tales against reckless swimming, against wandering too close to the river’s edge, against underestimating the silent pull of the tide.

Here's just a few:

Kappa (Japan)

Small but deadly, Japan’s kappa is a naughty little water goblin with a hollow in its head that holds life-giving water. While they’re known for playing pranks, their darker side is far more sinister. They lurk in rivers and ponds, waiting to drag humans—especially children—below.

Kappa.—From The Illustrated Night Parade of a Hundred Demons by Toriyama Sekien

Kelpie (Scotland)

A shape-shifting water spirit that appears as a beautiful horse. Anyone who mounts it finds themselves stuck, unable to dismount, as the kelpie plunges into the river, drowning and devouring its victim.

Nøkken (Scandinavia)

Another shape-shifting water spirit. This one plays a haunting violin to lure travelers to lakes and rivers. Those who listen too long are drawn in, unable to resist, until they slip beneath the surface and drown.

Theodor Kittelsen - Nøkken, 1887-92

Vodník (Czech & Slovak Folklore)

The Vodyanoy is often descri…

Vodník (Czech & Slovak Folklore)

The Vodyanoy is often described as an old man with a frog-like face, a tangled green beard, and long, dripping hair. His body, slick with algae and mud, is covered in dark fish scales. He rides through the river on a partially submerged log, sending up heavy splashes as he moves. Locals believe he is responsible for drownings. When angered, he is said to unleash his fury by breaking levees, flooding mills, and pulling both people and animals into the water’s depths.

Rusalka (Slavic Folklore)

The spirits of drowned women, often those who died violently. They haunt lakes and rivers, luring men with their beauty before entangling them in their long, wet hair and pulling them into the depths.

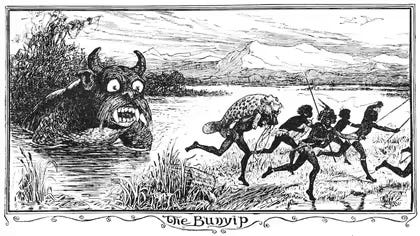

Bunyip (Australia)

A shadowy, terrifying creature that lurks in swamps and billabongs. Descriptions vary—some say it has flippers, others describe glowing eyes and a monstrous form—but all agree on its hunger for those who stray too close to the water.

Illustration by H. J. Ford

Wherever and whenever a culture emerges, there always seems to be something lurking below.

The Examined Life

I'm turning to the Tibetan sky burials for my thinking prompt this week because, to a Western mind like my own, it throws up so many interesting questions. If the body is merely a vessel, why do we place so much importance on its treatment after death? And can death be more meaningful when it serves a tangible purpose, such as feeding other living beings?

The source material for this week can be found here:

Hildegard of Bingen (2001) Selected Writings. Translated by M. Atherton

Spengler, O. (1932) Man and Technics: A Contribution to a Philosophy of Life. Translated by C.F. Atkinson

Michaelangelo. (1963) Complete poems and selected letters. Translated by C. Gilbert

And with that I'll leave you to get on with your day!

I hadn’t heard of Hildegarde before so this was extraordinary! A wonderful post - so filled with interesting points and ideas - as always! Reading Michelangelo’s grumpy words and then seeing the Sistine Chapel was lovely.

Spengler suggests Blake to me. The Marriage of Heaven and Hell:

Thus one portion of being is the Prolific, the other the Devouring.

To the devourer it seems as if the producer was in his chains; but it is not so, he only takes portions of existence, and fancies that the whole.

But the Prolific would cease to be prolific unless the Devourer as a

sea received the excess of his delights.

Some will say, "Is not God alone the Prolific?" I answer: "God only

acts and is in existing beings or men."

These two classes of men are always upon earth, and they should be

enemies: whoever tries to reconcile them seeks to destroy existence.