Issue #10: How Can People Design Their Communities for Themselves?

Alexander, Sontag and a Visual Representation of the Self

In the bleak midwinter / Frosty wind made moan / Earth stood hard as iron / Water like a stone

Bleh it's miserable out there. I don't know about you but the shorter days never seem to bring out my best. With that in mind, I'll keep the intro brief.

Nietzsche once wrote that ‘I mistrust all systematizers and avoid them. The will to a system is a lack of integrity.’ On this point, I couldn't disagree with him more. I find myself drawn inexorably towards any maniacal scheme that seeks to explain the nature of everything inside a single text; perhaps it's an inability to look honestly at the chaotic nature of existence.

Anyway, enter Christopher W. Alexander, who presents to us a language from which to design every building project ever. It's visionary, comprehensive, exacting to a fault and, I think, a lot of fun.

In the issue:

Christopher Alexander offers a generative language of architecture #architecture

Susan Sontag on the ‘latent antagonism’ between old worlds and new #literature

Heraclitus on how to think #philosophy

Carl Jung finds a visual representation of the self in ancient Tibetan art #psychology #art

How inferior quality can offer superior beauty: A celebration of Technicolour #film

As always, something to think about this week

How Can People Design Their Communities for Themselves? Christopher Alexander’s Generative Language of Architecture #architecture

Christopher Alexander was an architect and architectural theorist who had a difficult relationship with with his industry. In an editorial in Arch+ magazine in 1984, writers Nikolaus Kuhnert and Susanne Siepl claimed that ‘if one directs the conversation among architects to Christopher Alexander, then the condemnations and insults are quickly at hand.’

It isn't too difficult to unpick why this might be the case. His stated goal, which he set out to achieve through a trilogy of books in the 1970s titled The Timeless Way of Building, The Oregon Experiment, and A Pattern Language was to ‘lay the basis for an entirely new approach to architecture, building and planning, which will we hope replace existing ideas and practices entirely.’

At the core of the series, and here's where the architectural establishment may have taken issue, is the idea that ‘people should design for themselves their own houses, streets and communities,’ and what Alexander provides is a blueprint for how to go about doing that.

The second book in the series, A Pattern Language, outlines some recurring solutions to common design problems. It is structured around 253 ‘patterns’ which range from large-scale urban planning to specific architectural details, each providing a core solution that can be applied repeatedly, yet uniquely, in different contexts.

The patterns, which include things like ‘Industrial Ribbons’ (Pattern 42), ‘Small Public Squares’ (Pattern 61), ‘The Flow through Rooms’ (Pattern 131), and ‘Windows Overlooking Life’ (Pattern 192) are not to be understood in isolation, but rather as interconnected elements that weave together to form a language that can be used to design anything from a city to a child's bedroom. As Alexander puts it:

‘In short, no pattern is an isolated entity. Each pattern can exist in the world, only to the extent that is supported by other patterns: the larger patterns in which it is embedded, the patterns of the same size that surround it, and the smaller patterns which are embedded in it.’

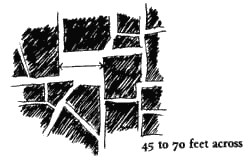

Small Public Squares (Pattern 61)

There is an attractively holistic perspective being advanced here about the notion of construction, and of the act of creating more generally.

‘This is a fundamental view of the world. It says that when you build a thing you cannot merely build that thing in isolation, but must repair the world around it, and within it, so that the larger world at that one place becomes more coherent, and more whole; and the thing which you make takes its place in the web of nature, as you make it.’

He has a way, does Alexander, of making you feel as though the process of human design and construction need not be conducted outside of the natural order of the world. Indeed, he emphasises that the patterns he lays out are not in fact creations at all, but discoveries, archetypal solutions to design problems that exist inherently in the world and are somehow uncovered, like a scientific principle, rather than built.

The analogy of architecture as language is an interesting one. The development of Alexander's language took place concurrently with Chomsky's generative grammar in linguistics, sharing with it the aim of describing how, by following certain rules, an infinite number of buildings or sentences can be produced from a finite number of elements.

He really did have the egotistical, maniacal, possibly brilliant belief that through his work, if it were to be adopted universally, he had designed every building project of every scale that would ever come to be or possibly could be conceived of. It's from here that those ‘anti-architecture’ criticisms stem.

Another critique thrown at Alexander and his followers was the accusation that he was ‘backward-looking.’ His project, by its very nature, exists in opposition to the individuality of modernist architecture, and much of architectural history besides. When we begin, as novices, to understand architecture, we start by looking at different eras and their defining styles - classical proportionality, gothic verticality, modernist minimalism - but here was a man seeking to build ‘as it has always been’ and to express time and place through small differences alone.

But Alexander would, I think, argue that design statements of this kind are not in fact the goal at all. Rather, we should be aiming for harmony:

‘It’s about whether, when you design an object, you want the user to be able to experience it and feel centred, or whether they feel catapulted out of the centre. In my work as an architect, the basic rule is to decide continuously, every minute of every hour, where exactly to place something so that it can achieve the greatest possible harmony with the evolving structure.’

It's an exhilarating place to be to have a book in your hands with chapter titles like ‘T-Junctions’ (Pattern 50), ‘Road Crossing’ (Pattern 54), and ‘Bus Stop’ (Pattern 92) and yet to genuinely feel in the company of something radical and transformative.

Here are just a few of his patterns to take into your next project:

Light on Two Sides of Every Room (Pattern 159): This pattern suggests that every room should have natural light entering from at least two sides, creating a balanced and softer light, reducing glare, and providing a more pleasant and inviting atmosphere.

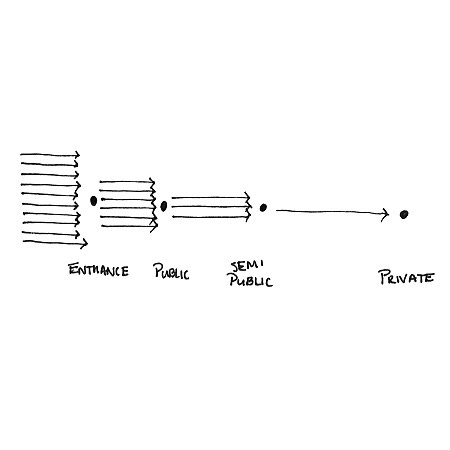

Intimacy Gradient (Pattern 127): Spaces in buildings should be arranged in a sequence that reflects increasing privacy. Public areas should be near the entrance, with more private areas further inside, creating a natural flow and making spaces feel more secure and comfortable as one moves deeper into a building.

Tree Places (Pattern 171): Designate and build places specifically around trees, letting them define the space. Trees can form the core of a room, courtyard, or even larger public spaces, bringing natural beauty and creating spaces that feel harmonious and rooted in the natural environment.

Building Edge (Pattern 160): The edges of buildings, where they meet the street or landscape, should be inviting and active, with places to sit, plantings, and opportunities for informal gatherings, helping to blur the line between indoor and outdoor spaces, making the transition from one to the other feel natural and pleasant.

Window Place (Pattern 180): Windows should have deep sills or seats where people can comfortably sit and enjoy the view, creating a natural pause, inviting contemplation, and offering a way to experience the changing light and seasons from indoors.

And, finally, my favourite...

Secret Place (Pattern 204): Every child (and perhaps every adult) needs a secret place to retreat, dream, and feel safe. These spaces can be small nooks, treehouses, or hidden corners of a garden. Secret places provide a sense of mystery and enchantment, inviting exploration and personal connection to a space.

Europe vs. America: Susan Sontag on Bridging the Gap Between Old and New #literature

One night, around 7 or 8 years ago, I was in the south of France with my wife. In an unlikely turn of events, the winds of fate had conspired to blow into the region not only my brother and his San Franciscan wife, but also said wife's childhood friend and her husband, also of American descent, leaving us in the situation dreaded by all British people of having to make friendly conversation with strangers, on our holiday.

We gathered in the warm evening air around a table in the centre of a beautiful town square. There was muted lighting, cobbled paving, an overpriced menu and the background noise of conversation that never rose above a hum. That was until the Americans began talking.

The pattern of the night was established as we were still shuffling our chairs under the table. From all around us there was tutting, huffing, occasional pointing, frequent eye-rolling, and a gradual expansion of the circumference of empty chairs around our table where the conversation was conducted several decibels above what would have been deemed acceptable by social convention.

These people, I really should point out, were absolutely lovely, but they were noisy, and, as someone with a pathological aversion to drawing attention of any kind, it was one of the longest evenings of my life.

Once the red face had died down, however, I was able to see just how accurately we were all conforming to national stereotypes. Here we had American honesty, confidence and unashamed openness set against European snobbish refinery with the British in the middle, awkwardly straddling the two whilst most likely massively overestimating the number of people who were looking at them. Global geopolitics over Tuna Niçoise.

Someone who straddled the divide between American and European culture with far more eloquence and discernment was Susan Sontag, an American of Lithuanian and Polish descent, who, in the immediate aftermath of the US-led invasion of Iraq, used the occasion of her Friedenspreis acceptance speech to discuss the uncomfortable relationship between her home country and the European community that was uniting to celebrate her achievements.

For her, the 'latent antagonism' between Europe and America is 'at least as complex and ambivalent as that between parent and child.' In the same way that younger generations so often seek to define themselves in opposition to the values of their parents' generation, so too did America, the child of Europe, set out to shake free from the shackles of debilitating convention.

She summarises some of our polarised values as below:

'American innocence and European sophistication; American pragmatism and European intellectualizing; American energy and European world-weariness; American naïveté and European cynicism; American goodheartedness and European malice; American moralism and the European arts of compromise.'

She's characteristically precise here, but there's not much that is new. As she says herself — we probably 'know the tunes.' Where she gets characteristically interesting is in her discussion of how to bridge the gap, a project she saw as increasingly necessary in a political climate of European skepticism of American military action on the global stage.

For her, the key to understanding the way forward is found in the unavoidable opposition between ‘old’ and ‘new,’ which serve as ‘the perennial poles of all feeling and sense of orientation in the world.’ Life, for Sontag, is just a series of negotiations between these two opposites, and she warns against falling into the trap of thinking we have to choose just one path.

'We cannot do without the old, because in what is old is invested all our past, our wisdom, our memories, our sadness, our sense of realism. We cannot do without faith in the new, because in what is new is invested all our energy, our capacity for optimism, our blind biological yearning, our ability to forget—the healing ability that makes reconciliation possible.'

If we can't do without the 'old,' as embodied by a culturally rich but world weary Europe, and we can't do without the 'new,' as embodied by an optimistic but naive America, then we have to find a way of marrying up the two. The answer to that little puzzle, she suggests, might be found in literature.

If there is anyone with an ability to combat feelings of separateness, it's writers, with their ability to not just transmit myths but to make them, with their gravitation towards the oppositional and the contrary, their 'counter-statements to the reigning pieties.' If we need a response to a cultural doctrine, then where better to turn than towards literature, which Sontag argues 'might be described as the history of human responsiveness to what is alive and what is moribund as cultures evolve and interact with one another.'

To have access to literature is to be offered a fresh perspective to aid us in our ‘escape’ from ‘the prison of national vanity.’ It is a ‘passport to enter a larger life.’ Literature is freedom.

It's also empathy. Literature is the tool that helps us to understand those characterised as 'other,' it is the mechanism by which we can straddle divides like the one I felt materialising around me on a balmy night in France several years ago.

Sontag, a figure enthusiastically embraced by both American and European culture, her brilliance rising above any divide between 'new' and 'old,' obviously puts it best:

'Literature can train, and exercise, our ability to weep for those who are not us or ours.'

Extract of the Week #philosophy

Heraclitus on how to think:

‘The soul is dyed the color of its thoughts. Think only on those things that are in line with your principles and can bear the light of day. The content of your character is your choice. Day by day, what you do is who you become. Your integrity is your destiny - it is the light that guides your way.’

Image of the Week #psychology #art

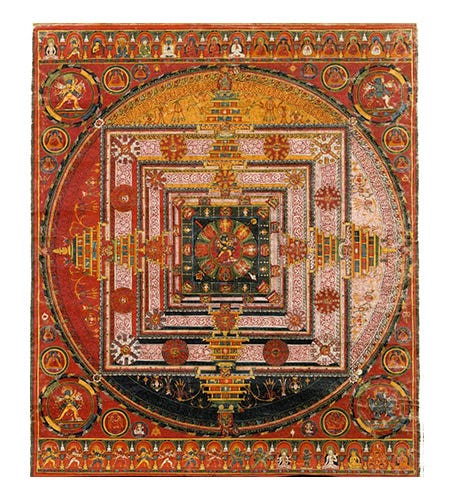

Mandala of Jnanadakini, Tibet, late 14th century

The concentric symmetry of a mandala is strangely seductive. Its intricate patterns seem to exist apart from humankind, as though created by the universe itself as a clue or a puzzle; something that hints at secrets but doesn't really reveal them, something that promises guidance. Like a map of an old town, it draws you inevitably into its centre, a journey inward towards the still point in a turning world.

Carl Jung certainly found them captivating and, never a man to leave a puzzle unsolved, he had all sorts of fascinating ideas about their significance.

For him, a mandala was a symbolic representation of the self, a specific centre of the personality not to be confused with the ego:

‘The self, though on the one hand simple, is on the other hand an extremely composite thing, a “conglomerate soul,” to use the Indian expression.’

They symbolise, for Jung, a kind of central point within the psyche, like a hub within our mind where everything connects and gets organised. This center isn't just a focal point; it’s also a source of energy that influences everything around it:

‘The energy of the central point is manifested in the almost irresistible compulsion and urge to become what one is, just as every organism is driven to assume the form that is characteristic of its nature, no matter what the circumstances.’

I like this, as a concept. At our core we are quintessentially our true selves - quiet, still and grounded - but our character also comprises a periphery of paired opposites that make up our complete personality.

Herein lies the comforting aspect of mandalas for me. I can, after all, claim to love people whilst wanting to be on my own, claim to have a discerning relationship with culture whilst watching another rerun of Friends, claim to appreciate the beauty of the natural world whilst keeping my curtains closed until lunchtime.

Here's a few more to enjoy.

The Collection | The Beauty of Technicolour #film

Technicolor revolutionised cinema with its three-strip process. Three separate film reels, each capturing a separate primary colour, were used to produce a black-and-white image that corresponded to its specific colour. These images were then dyed (cyan for red, magenta for green, yellow for blue), meticulously aligned and then printed onto a single film strip and our collective memories.

The process produced colours that were deeply saturated, slightly exaggerated, and often had a warmer, more dreamlike quality than the colours produced by modern techniques. There is somehow more life in the colour, a warmth to the imperfection, similar to the subtle tremor of a vinyl record whispering like a voice from the past.

Below, I've collected a few stills to aid your time travel:

Becky Sharp (1935)

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

Gone with the Wind (1939)

The Wizard of Oz (1939)

The Red Shoes (1948)

The Ladykillers (1955)

The Examined Life

The famous Heraclitus passage rejects the idea that our thoughts are fleeting, suggesting instead that, incrementally, they leave a lasting impression on who we are. Do you agree that integrity is a process of self discipline rather than something innate? If so, how can we cultivate a mindset that ensures our thoughts consistently align with our moral values? Is there any concrete danger in allowing our abstract thoughts to drift away from our principles?

If You Enjoyed It…

Go further by exploring this week's reading list:

Alexander, C. et al (1977) A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction

Sontag, S (2003) Literature as Freedom

Heraclitus (2003) Fragments

Jung, C. (1944) Psychology and Alchemy

Or share with your people here:

Thank you, as ever, for your support.

Gigantic fan of Pattern Language! When I built my house we used many of the patterns (window on two walls, nothing more than 12’ from a source of natural light. He was a genius.

An interesting historical note is that while architecture didn’t embrace it (it was more about money than any real threat - building his way is expensive), software did. The design patterns movement that started in the 1990s was consciously derived from his work and had a huge effect on how software was designed.

The patterns were different, like “Leaf-node”, and they really worked to give structure to a chaotic discipline.

Thanks for sharing this my first reading of your newsletter. Your writing and curation are both superb. Very enjoyable x