‘What is there in thee, Moon! That thou should'st move my heart so potently? When yet a child I oft have dried my tears when thou hast smil’d’

So said John Keats in 1818's Endymion, and he isn't alone in harbouring some special affection for the celestial lamp that illuminates the mysterious hours of night. References to the light of the moon shimmer through literary history, so here are a few handfuls to grasp at...

Spring Moon at Ninomiya Beach, Hasui Kawase, 1931

The textbooks tell us that the sun is approximately 400 times larger than the moon which, in comparison to that epic giver of light and of life, appears weak, pale and watery. This was a fact not lost on Shelley, for whom the moon was a lonely and joyless rock:

‘Art thou pale for weariness / Of climbing heaven and gazing on the earth, / Wandering companionless / Among the stars that have a different birth, / And ever changing, like a joyless eye / That finds no object worth its constancy?’

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Art thou pale for weariness, 1821

Or Rulfo, who's moon in Pedro Paramo seems ashamed even to exist in the same sky as the burning sun of the day:

‘The sky was filled with fat stars, swollen from the long night. The moon had risen briefly and then slipped out of sight. It was one of those sad moons that no one looks at or pays attention to. It had hung there a while, misshapen, not shedding any light, and then gone to hide behind the hills.’

Juan Rulfo, Pedro Páramo, 1955

T.S. Eliot is also alive to the misshapen quality of the moon, scoffing at our romanticisation of what to him is nothing more than ‘an old battered lantern’:

‘I observe: "Our sentimental friend the moon! / Or possibly (fantastic, I confess) / It may be Prester John’s balloon / Or an old battered lantern hung aloft / To light poor travellers to their distress.”’

T.S. Eliot, Conversation Galante, 1917

Plage au Clair de Lune, Léon Spilliaert

And, famously, Romeo emphasises the radiant beauty of his Juliet through comparison to the weak light of the ‘envious’ moon:

‘But soft, what light through yonder window breaks? / It is the East, and Juliet is the sun. / Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon, / Who is already sick and pale with grief / That thou, her maid, art far more fair than she. / Be not her maid since she is envious. / Her vestal livery is but sick and green, / And none but fools do wear it. Cast it off.’

William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet (Act 2 Scene 2), 1597

Moonlight and Lamplight, Winifred Nicholson, 1937

But the moon is clearly more than a weak and battered old rock. That ‘pale’ and ‘watery’ light casts an air of mystery and enchantment, recasting objects caught in its beam into a world of legends and dreams. Shakespeare, of course, knew this well. The madness and magic of his Midsummer Night's Dream is awash with the moon's strange light, most beautifully when Titiana says:

'Be kind and courteous to this gentleman; / Hop in his walks and gambol in his eyes; / Feed him with apricocks and dewberries, / With purple grapes, green figs, and mulberries; / The honey-bags steal from the humble-bees, / And for night-tapers, crop their waxen thighs, / And light them at the fiery glow-worm’s eyes, / To have my love to bed and to arise; / And pluck the wings from painted butterflies, / To fan the moonbeams from his sleeping eyes. / Nod to him, elves, and do him courtesies.'

William Shakespeare, Midsummer Nights Dream (act 3, scene 1), 1595

We find, in a completely different era and artform, similar sentiments to Shakespeare’s in Neil Young’s Harvest Moon. It's not just fairies and pixies who hold their revels by moonlight:

‘But there's a full moon risin' / Let's go dancin' in the light / We know where the music's playin' / Let's go out and feel the night’

Neil Young, lyrics from Harvest Moon, 1992

Pedro Figari, Patio, 1880-1938

What connects these two distant artists? I think Henri-Frédéric Amiel might argue it's something like eternal youth, finding moon-love, as he does, to be a good barometer for youth and happiness:

‘Tell me what you feel in your room when the full moon is shining in upon you and your lamp is dying out, and I will tell you how old you are, and I shall know if you are happy.’

Henri-Frédéric Amiel, Journal Intime, 1883

And we don't have to turn to literature to be enchanted by the moon. She is magic enough in the real world of science. Ask Kepler:

‘If the earth should cease to attract its waters to itself all the waters of the sea would be raised and would flow to the body of the moon.’

Johannes Kepler, Somnium, 1634

An illustration from Jules Verne’s 1865 novel From the Earth to the Moon

Or Rachel Carson (who's science is so beautifully rendered in words that she deserves her place alongside the very best writers of ‘literature’):

‘The next time you stand on a beach at night, watching the moon’s bright path across the water, and conscious of the moon-drawn tides, remember that the moon itself may have been born of a great tidal wave of earthly substance, torn off into space. And remember if the moon was formed in this fashion, the event may have had much to do with shaping the ocean basins and the continents as we know them.’

Rachel Carson, The Sea Around Us, 1951

But there's another side to the moon of literary imaginings. The dreamlike enchantment and playful magic of moonlight can often drift over into witchery and menace. Try to find a book cover in the gothic horror genre that doesn't take advantage of the elemental dread of the moon at night. This is the moon of vampires and werewolves, whose pale light hides the dreadful unknown:

‘The wind had fallen, and there was a still night and a full moon. At about ten o’clock Stephen was standing at the open window of his bedroom, looking out over the country. Still as the night was, the mysterious population of the distant moon-lit woods was not yet lulled to rest. From time to time strange cries as of lost and despairing wanderers sounded from across the mere. They might be the notes of owls or water-birds, yet they did not quite resemble either sound. Were not they coming nearer?’

M.R. James, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, 1904

‘The moon hung low in the sky like a yellow skull. From time to time a huge misshapen cloud stretched a long arm across and hid it. The gas-lamps grew fewer, and the streets more narrow and gloomy. Once the man lost his way and had to drive back half a mile. A steam rose from the horse as it splashed up the puddles. The sidewindows of the hansom were clogged with a grey-flannel mist.’

Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray, 1890

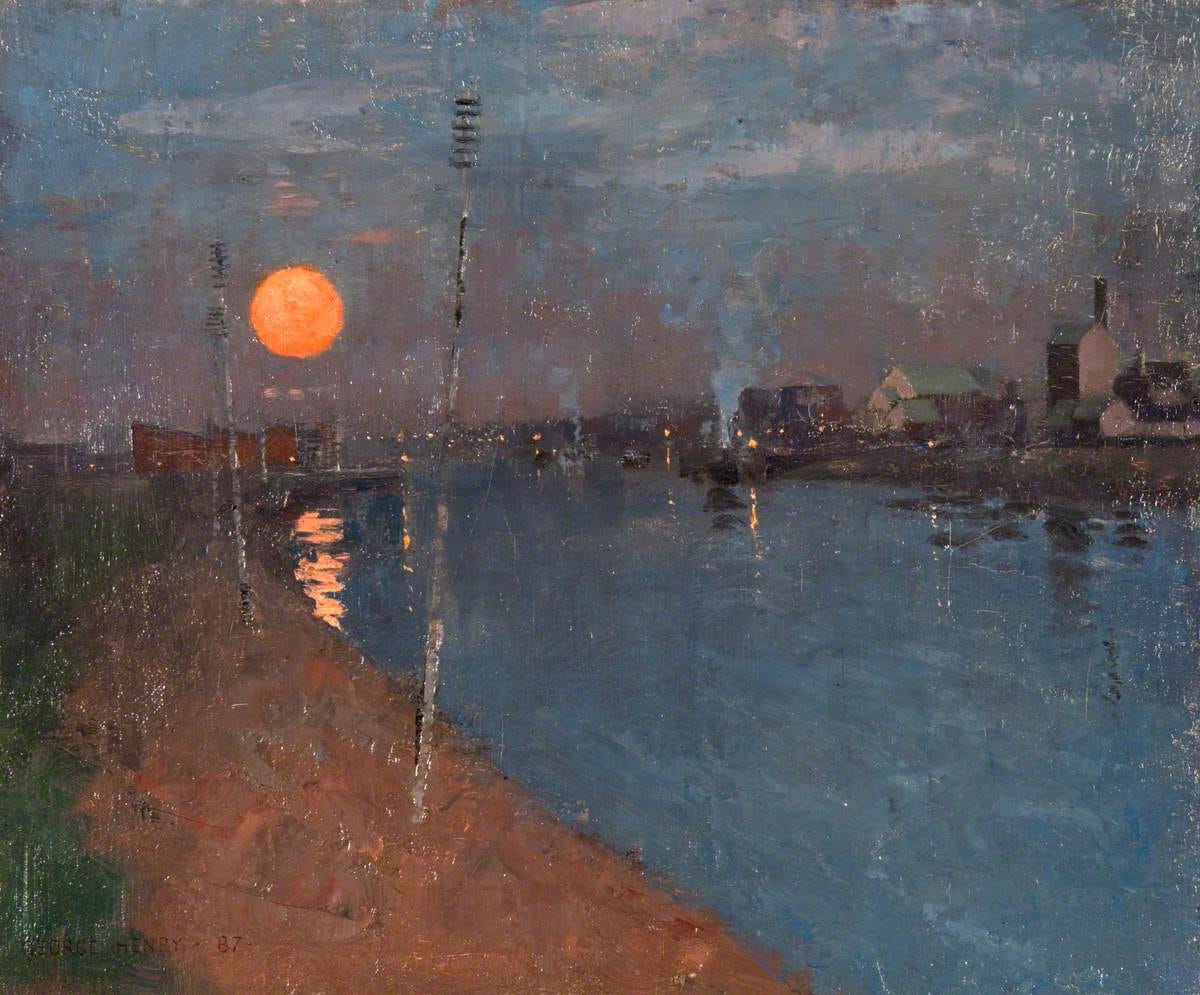

River Landscape by Moonlight, George Henry, 1887

And even my liberally wielded scythe couldn't find where to chop this beautiful moon-poem from Sylvia Plath, so here it is in its entirety:

‘This is the light of the mind, cold and planetary. / The trees of the mind are black. The light is blue. / The grasses unload their griefs at my feet as if I were God, / Prickling my ankles and murmuring of their humility. / Fumy spiritous mists inhabit this place / Separated from my house by a row of headstones. / I simply cannot see where there is to get to.

The moon is no door. It is a face in its own right / White as a knuckle and terribly upset. / It drags the sea after it like a dark crime; it is quiet / With the O-gape of complete despair. I live here. / Twice on Sunday, the bells startle the sky – / Eight great tongues affirming the Resurrection. / At the end, they soberly bong out their names.

The yew tree points up. It has a Gothic shape. / The eyes lift after it and find the moon. / The moon is my mother. She is not sweet like Mary. / Her blue garments unloose small bats and owls. / How I would like to believe in tenderness – / The face of the effigy, gentled by candles, / Bending, on me in particular, its mild eyes.

I have fallen a long way. Clouds are flowering / Blue and mystical over the face of the stars. / Inside the church, the saints will be all blue, / Floating on their delicate feet over cold pews, / Their hands and faces stiff with holiness. / The moon sees nothing of this. She is bald and wild. / And the message of the yew tree is blackness – / blackness and silence.’

Sylvia Plath, The Moon and the Yew Tree, 1961

Less gothic, but equally terrifying, is Roger Wray in the Atlantic:

‘The moon is airless, waterless, lifeless — a corpse of a world; and its principal glory is (as the ladies say) ‘not her own.’ The total surface visible to us is approximately twice the size of Europe, and one must picture it as a barren continent of peak and precipice, crag and crater, with mountains standing fang-like in frozen light, and valleys plunged in utter blackness. There is no bush or tree, no blade of grass or smudge of lichen; no sound of bird or beast; no chuckle of water, or whine of midge. The petrified silence threatens to burst the eardrums.’

Roger Wray in The Atlantic, March 1922

Meanwhile, Guy de Maupassant somehow manages to convey the beauty of the moon alongside a looming sense of unease:

‘Down yonder, following the undulations of the little river, a great line of poplars wound in and out. A fine mist, a white haze through which the moonbeams passed, silvering it and making it gleam, hung around and above the mountains, covering all the tortuous course of the water with a kind of light and transparent cotton.

The priest stopped once again, his soul filled with a growing and irresistible tenderness. And a doubt, a vague feeling of disquiet came over him; he was asking one of those questions that he sometimes put to himself. "Why did God make this?’

Guy de Maupassant, Clair De Lune, 1883

Kobayashi Kiyochika, Pathway to a shrine, 1877

It's the new moon in particular that provokes such disquiet, a fact rendered in song since the middle ages:

‘Last night I saw the new moon clear / With the new moon in her hair / And that is a sign since we were born / That means there'll be a deadly storm’

Traditional British, Ballad of Sir Patrick Spence, Middle Ages

Perhaps here we locate the source of the moon's association with oncoming but as yet unknown horror, but such an association doesn't prevent us from admiring the frail beauty of a world lit by moonshine:

‘See yonder fire! It is the moon slow rising o'er the eastern hill. It glimmers on the forest tips, and through the dewy foliage drips in little rivulets of light, and makes the heart in love with night.’

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in Christus, the Golden Legend, 1872

‘The moon swam up through the films of misty cloud, and hung, a golden glorious lantern, in mid-air; and, set in the dusky hedge, the little green fires of the glowworms appeared. He sauntered slowly up the lane, drinking in the religion of the scene, and thinking the country by night as mystic and wonderful as a dimly-lit cathedral. He had quite forgotten the “manly young fellows” and their sports, and only wished as the land began to shimmer and gleam in the moonlight that he knew by some medium of words or colour how to represent the loveliness about his way.’

Arthur Machen, The Hill of Dreams, 1907

‘Mild Splendor of the various-vested Night! / Mother of wildly-working visions! hail! / I watch thy gliding, while with watery light / Thy weak eye glimmers through a fleecy veil; / And when thou lovest thy pale orb to shroud / Behind the gather'd blackness lost on high; / And when thou dartest from the wind-rent cloud / Thy placid lightning o'er th' awakened sky. / Ah, such is Hope! As changeful and as fair! / Now dimly peering on the wistful sight; / Now hid behind the dragon-wing'd Despair: / But soon emerging in her radiant might / She o'er the sorrow-clouded breast of Care / Sails, like a meteor kindling in its flight.’

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Sonnet XVIII. To The Autumnal Moon, 1796

Perhaps, after all, boyishly naïve Romeo gets it all wrong when he makes Juliet his sun. The blazing glory of sunlight is masculine in its desire to burn the eyes and singe the flesh. The silvery light of the moon is not weak in contrast, it just has a touch of feminine modesty, a beauty so brilliant it needn't draw attention to itself:

‘Sometimes in the afternoon sky the moon would pass white as a cloud, furtive, lusterless, like an actress who does not have to perform yet and who, from the audience, in street clothes, watches the other actors for a moment, making herself inconspicuous, not wanting anyone to pay attention to her.’

Marcel Proust, À la recherche du temps perdu, 1913-1927

Rising Moon, St Ives Bay, Cornwall, Albert Julius Olsson, exhibited 1905

From my personal archive a song lyric for a distant love, now remote in time as well as space:

High moon shining here and there

Bless her with your beams

Touch her lip like a snowflake

Send to her sweet dreams

May she wish upon you

As I wish upon you

All may be well

Until the time that we meet again

Which time alone will tell

Thank you for this lovely collection of engaging words & memorable images. You have a gift for the fluid integration of seemingly disparate works into a beautifully crafted & unified thematic perspective. It is a rare talent!