Welcome to the inaugural issue of The Humanities Library, an open notebook from a directionless man turning to the bookshelf in search of guidance.

I'll start this week with something of a mission statement, found in an unlikely place. Then, as I begin something new, the ancient Greek word for ‘the start of the bad thing' is playing on my mind - I can't think why that might be - so I’ve written something about that as well.

If you're interested in joining me to see how this goes, please do subscribe; I would be eternally grateful for your act of generosity.

In the issue:

E.F. Schumacher on the humanities #education

The start of the bad thing #linguistics

Nostalgia and memory by Juan Rulfo #literature

Alfred Wallis and the hypocrisy of the privileged #art

Just where is the centre of the universe? #religion #mythology

As always, something to think about this week

Why Do We Need the Humanities? E.F. Schumacher on What an Education Really Entails #education

There's a gloomy picture emerging for the study of the Humanities in 2024. In recent years, Universities including Roehampton, the University of Kent and the University of East Anglia have closed or downsised their Humanities departments. Sheffield Hallam announced the suspension of its English Literature programme, and the University of Huddersfield axed its Linguistics provision.

At times, it feels as though such developments are welcomed by a governing class that seems incapable of decoupling the concept of education from notions of material or professional success. It's as though education exists for the sole purpose of securing passage into a financially secure profession, and when a subject fails to point towards an alumni community with an impressive average income, questions begin to be asked about the 'value' of the education being provided to the university's paying ‘customers.'

As the world lauds the high-priests of progress in the fields of Science and Technology, the study of the Arts, Literature or Philosophy is becoming an increasingly idiosyncratic choice. As someone who followed that path myself, I can speak from experience of the feelings evoked by this two-tiered system. If you're not studying a so-called STEM subject (Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths, for the uninitiated) then you're really not much use to an employer or to the economy.

As I look for ways to articulate what humanity is at risk of losing if it continues down this path, I find myself drawing from unlikely source material. I stumbled across it buried deep into the pages of a book which is ostensibly about economics.

In 'Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered' (1972) E.F. Schumacher, in between putting forth his economic rationale for sustainable and human-scale development, also lays down some rather convincing ideas about the role of a Humanities education.

His argument is that, whilst scientific concepts - he points to the second law of thermodynamics as an example - might have practical applications to specific scientific enquiries, they do not provide ideas by which humankind can live. They provide nothing by way of direction for how to apply supposedly 'neutral' scientific understandings in the service of advancing the human experience.

A society educated exclusively in the sciences might, to illustrate with a contemporary example, know how to build artificial intelligence, but not whether it should. There is nothing, Schumacher says, in a STEM education that provides the necessary insights for the consideration of such decisions. As he puts it, whether scientific insights 'enrich humanity or destroy it depends on how they are used.'

The ‘know-how’ side of the picture is not without it's own value, of course, but for Schumacher the ‘know-how’ of Science ‘is nothing by itself; it is a means without an end, a mere potentiality, an unfinished sentence.' He summarises it brilliantly with the aphorism that know-how 'is no more a culture than a piano is music.'

‘Know-how’, then, whilst undoubtedly important, should nonetheless come as a secondary concern after the primary role of education which is the transmission of ideas of value, ideas that give us a reasonable idea of what to do with our powers, ideas that teach us nothing less than 'what to do with our lives.' Education, true education, should provide the means by which we finish that 'unfinished sentence.'

‘know-how is no more a culture than a piano is music’

There's an angle to this argument that takes place on a national or even international scale. As we contemplate a world consumed by artificial intelligence, we'd be forgiven for worrying about the grounding in ethics and social sciences of those who hold our futures in their hands. But this is personal as well; it’s about our very capacity to think, our capacity to engage with the world around us, our ability to live a fulfilling existence.

Schumacher argues that when we think ‘we can do so only because our mind is already filled with all sorts of ideas with which to think.’ They are the ‘instruments through which we look at, interpret, and experience the world.’ Thinking, for Schumacher, simply involves the application of pre-existing ideas to a given situation or new set of facts, so the way in which we interpret and experience the world is very much dependent on the ideas we have committed to memory. It reads something like cognitive load theory before that theory had a name.

Let's put this, then, in terms more common to educational discourse in the years since Schumacher's essay. A long-term memory that provides its owner with immediate access to the greatest ideas that have been thought and written ensures that the working memory is free to assimilate any new data at hand without risking overload. Put simply, the knowledgeable brain is a better and more supple apparatus to deploy to the task of thinking.

But there's also a warning in Schumacher's words about what happens to a mind that lacks such ideas. Without the necessary insights with which to interpret new information, the world can appear unintelligible, and the resulting feelings of estrangement can be unbearable.

That's what we're fighting against here. When we talk of education, we must hold onto the notion that we mean something more than mere training, something more than mere knowledge of facts. We're talking of nothing less than compiling a 'tool-box' of powerful ideas, without which 'the world must appear [...] as a chaos, a mass of unrelated phenomena, of meaningless events.'

A man without such a tool-box 'is like a person in a strange land without any signs of civilisation, without maps or signposts or indicators of any kind. Nothing has any meaning to him; nothing can hold his vital interest; he has no means of making anything intelligible to himself.'

When a person is so unrooted from the world and society around them, we have a big issue. Their experience is characterised by an emptiness, creating a vacuum which 'may only too easily be filled by some big, fantastic notion -- political or otherwise -- which suddenly seems to illumine everything and to give meaning and purpose to our existence.' There's a pertinence to Schumacher's words in 2024 that needn't be spelt out.

What this ultimately comes down to is an argument about which ideas to fill our intellectual tool-box with. Which ideas allow us to interface with the people and environment around us in a way that enables us to extract meaning from this thing we call existence? As we contemplate the sneering consensus that places the insights of the Humanities as secondary to those of the Sciences, we could do a lot worse than quoting Schumacher in response. He asks:

'What do I miss, as a human being, if I have never heard of the Second Law of Thermodynamics? The answer is: nothing. And what do I miss by not knowing Shakespeare? Unless I get my understanding from another source, I simply miss my life.'

Where Did it All Start to Go Wrong? #linguistics

When stuff goes wrong, like badly wrong, the human impulse is to analyse where it all began to go off track. Where was the butterfly that flapped its wings and got us into this mess?

The financial crash of 2008 began with the fall of Lehman Brothers, but you can have all sorts of fun tracing it back further; housing demand, economic incentives in the mortgage markets, bonus culture in the financial sector etc. The nature of cause and effect is that there is always further back to go, always another moment to point to and say - if only we hadn’t done that.

The ancient Greeks had a term for this moment; they called it arkhe kakon. Kakon comes from the Greek term kakos, meaning ‘bad’ (think cacophony) whilst arkhe means ‘beginning’ or ‘original’ (think archetype), giving us a phrase that roughly translates as ‘the beginning of the bad thing.’

The great arkhe kakon of Greek mythology is the stealing away of Helen, wife of the Greek hero Menelaus, by the Trojan Prince Paris, which set in motion the events that lead up to the epic Greek-Trojan war that would last a decade.

One day, when we finally burn this planet to its crust, what will the last surviving members of our species point to as the moment we took our wrong turn, the moment the bad times began, our great arkhe kakon? Its impossible to know, but whose taking bets on whether it has already happened?

Extract of the Week #literature

This week, the great Juan Rulfo on the nostalgia of a childhood town long forgotten.

There you'll find the place I love most in the world. The place where I grew thin from dreaming. My village, rising from the plain. Shaded with trees and leaves like a piggy bank filled with memories. You'll see why a person would want to live there forever. Dawn, morning, mid-day, night: all the same, except for the changes in the air. The air changes the color of things there. And life whirs by as quiet as a murmur...the pure murmuring of life.

Juan Rulfo, Pedro Paramo, 1955

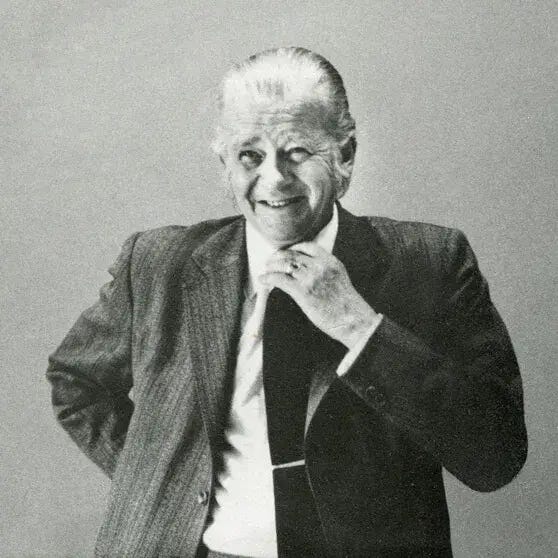

Image of the Week #art

This is 'Four Boats,' an imaginatively titled piece from Alfred Wallis painted on cardboard in approximately 1939.

I find the story behind Alfred Wallis fascinating. Discovered by artists Christopher Wood and Ben Nicholson, who seemingly caught sight of him at his easel through the window of his St. Ives home after spotting some paintings nailed to the door, Wallis was every bit the humble man who found himself caught up in the early 20th century rush to celebrate artists without a conventional Western education.

Through his ‘primitive’ work, like Rousseau in France, Wallis came to embody creative freedom and, as a born and bred St. Ives man-of-the-sea, a connected-to-the-environment authenticity. His work is ‘primitive’ in a few ways; almost childlike, painted with the kinds of paint used to spruce up the boats themselves and, in this case, directly onto whatever piece of cardboard was lying around his house. For those educated and metropolitan artists weary of refinery and seeking sources of creative authenticity, this stuff was gold, speaking of a depth of experience increasingly alien to those in their privileged peer groups.

The reason I find Wallis’ story fascinating, however, is what it teaches us about the thought processes of elitism. Whilst Nicholson appears to have done plenty to promote Wallis' work to his closed network of peers, the prices he paid for the works amounted to the value of a meal or two.

Despite his numerous and wealthy patrons, Wallis continued to live in poverty until his death, with Nicholson himself defending the fact that he didn’t do more to support his friend financially by claiming that he didn’t want to remove Wallis’ ‘urge to work.’ If his art was a product of his hardship, this argument goes, then we shouldn’t lift him up out of it and into an unproductive life of comfort.

You can’t help but wonder if a similar fear for the authenticity of his work clouded his own desire to get paid for it.

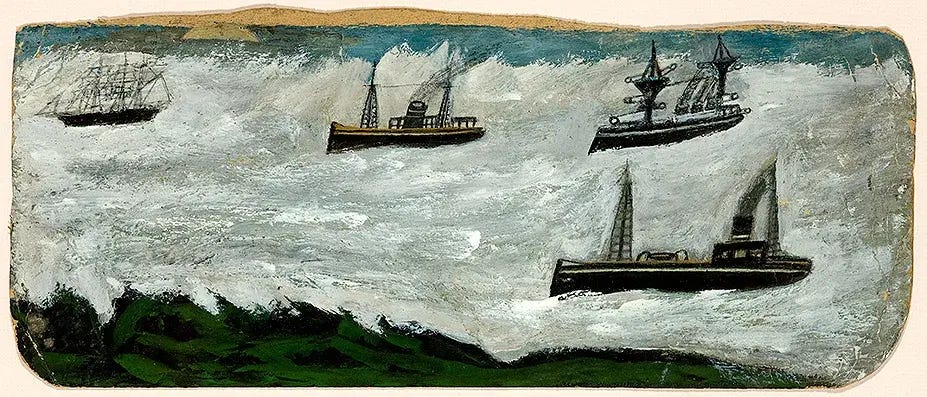

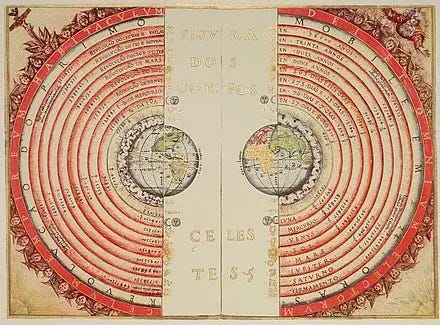

The Collection | Ways of Conceptualising the Centre of the Universe #religion #mythology

Human civilisation has always sought to identify the centre of things, to locate the core of the universe, and for the most part we've been pretty creative with it. This week, then, a collection of my favourite conceptualisations of the centre of the universe!

11 - In Greece, in the 4th century BC, philosophers developed the geocentric model, proposing that the center of the Universe lies at the center of a spherical, stationary Earth, around which the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars rotate.

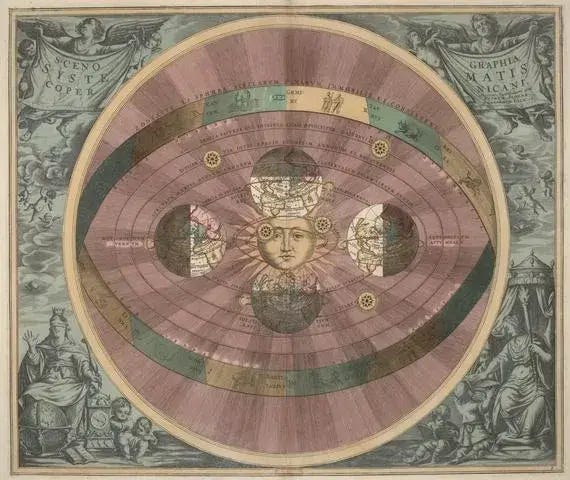

10 - With the development of the heliocentric model by Nicolaus Copernicus in the 16th century, humans came to believe that the planets (including Earth) orbited around the sun. So far, so good. But with this understanding came the misguided extrapolation that the sun must therefore be the centre of the universe. Not so good.

9 - Common to many religions and mythological traditions, the axis mundi connects the spiritual and physical realms. In Christianity, Jacob's Ladder is a ladder leading to heaven that was featured in a dream the biblical Patriarch Jacob had during his flight from his brother Esau in the Book of Genesis.

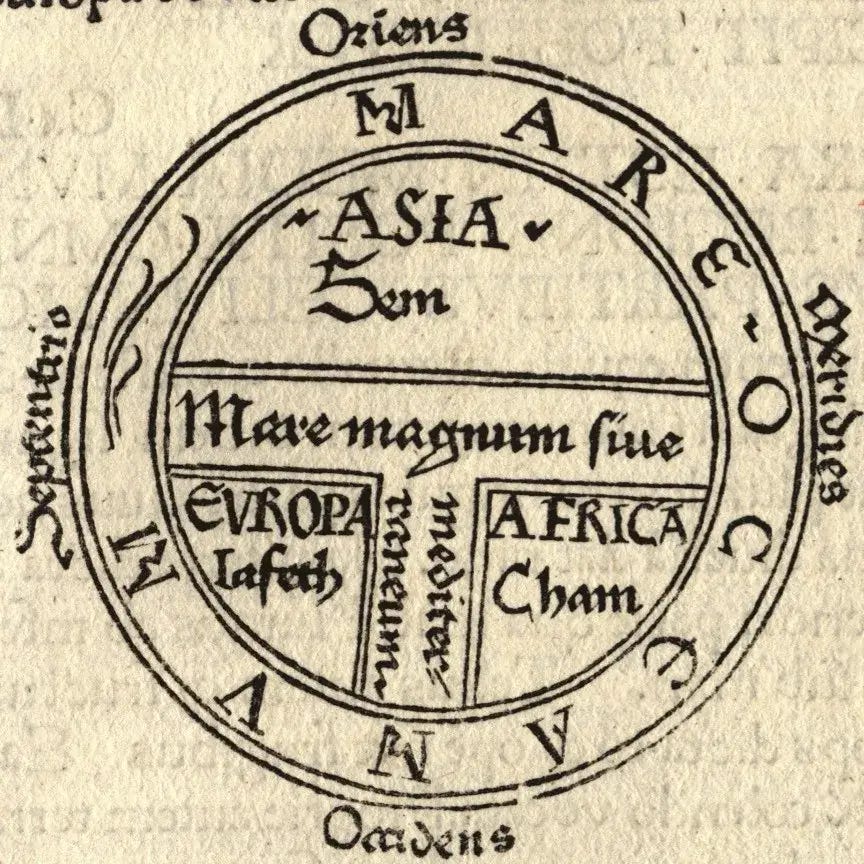

8 - The Isidoran map, also known as the T-O map, is a type of early world map that represents world geography as first described by the 7th-century scholar Isidore of Seville. In it, Jerusalem was generally represented as the centre of the world.

7 - In the Nahuatl language, Teotihuacán is often interpreted to mean 'birthplace of the gods.' The name reflects the Aztec belief that Teotihuacán was at the center of all creation. Here, great pyramids were erected with staircases that represented the ascent to heaven.

6 - In ancient Mesopotamian cosmology, the Earth was seen as a flat disk surrounded by a cosmic ocean, with the city of Babylon often considered the world's centre.

5 - The Kunlun is a mountain or mountain range in Chinese mythology, known in Taoist literature as ‘the mountain at the middle of the world.’ To ‘go into the mountains’ meant to dedicate oneself to a spiritual life.

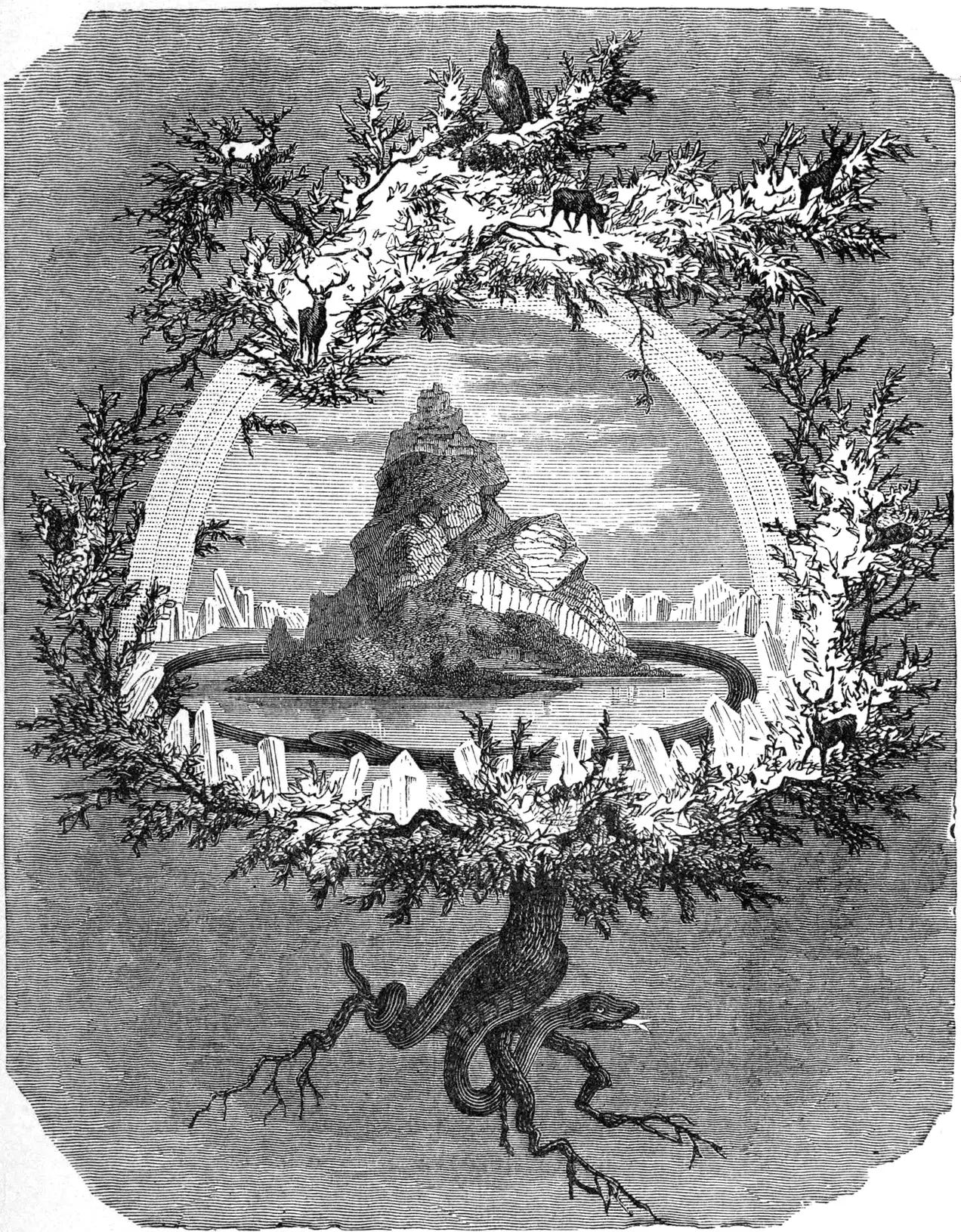

4 - In Norse mythology, the Yggdrasil was a sacred tree thought to connect the planes of the underworld and the sky with that of the terrestrial realm.

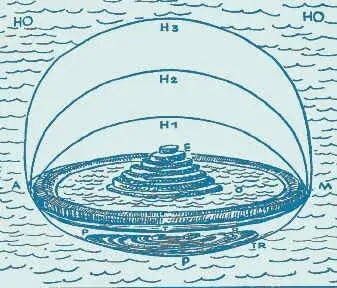

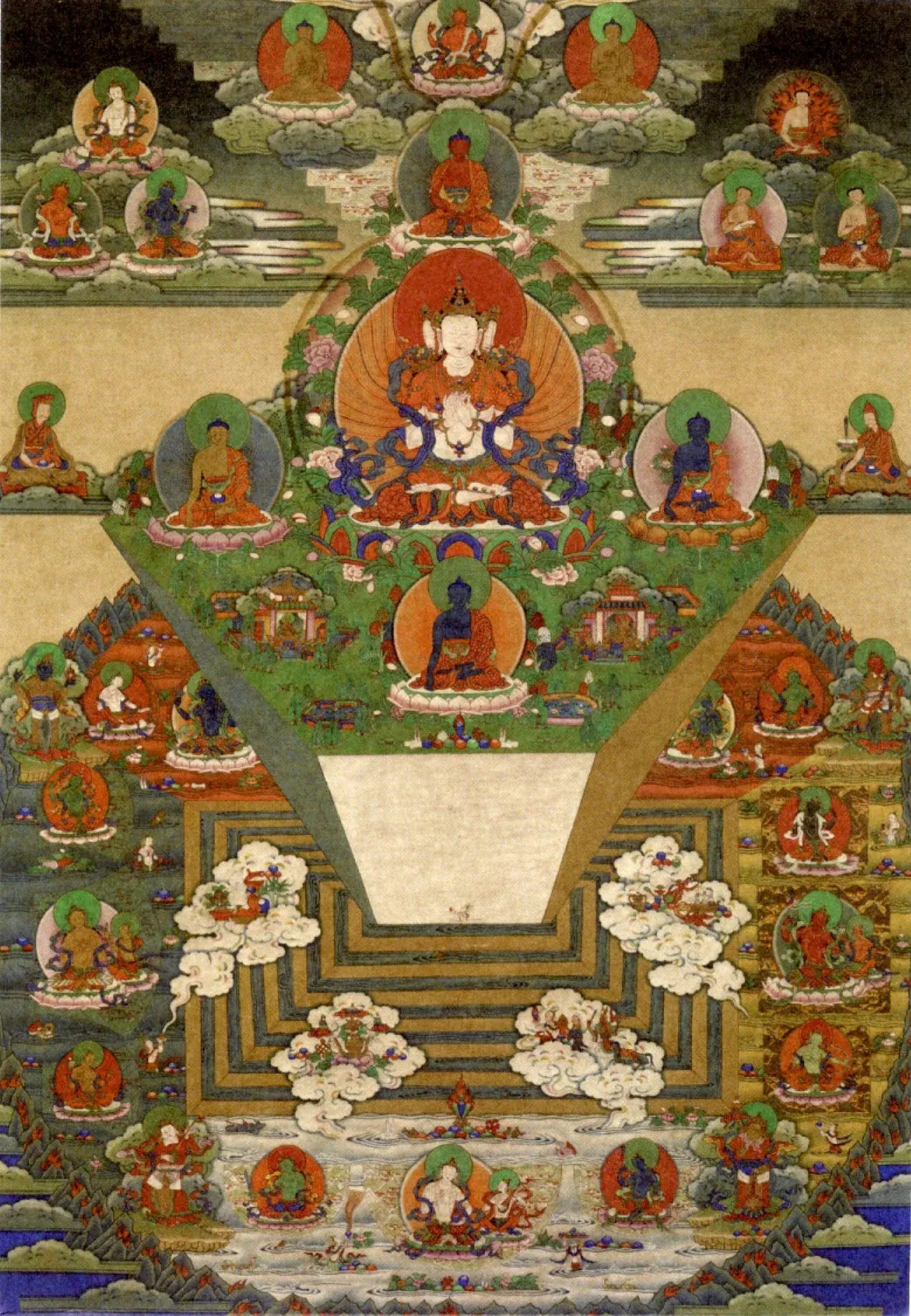

3 - In Hindu and Buddhist cosmology, Mount Meru is a mythical golden mountain that stands in the centre of the universe and is the axis of the world.

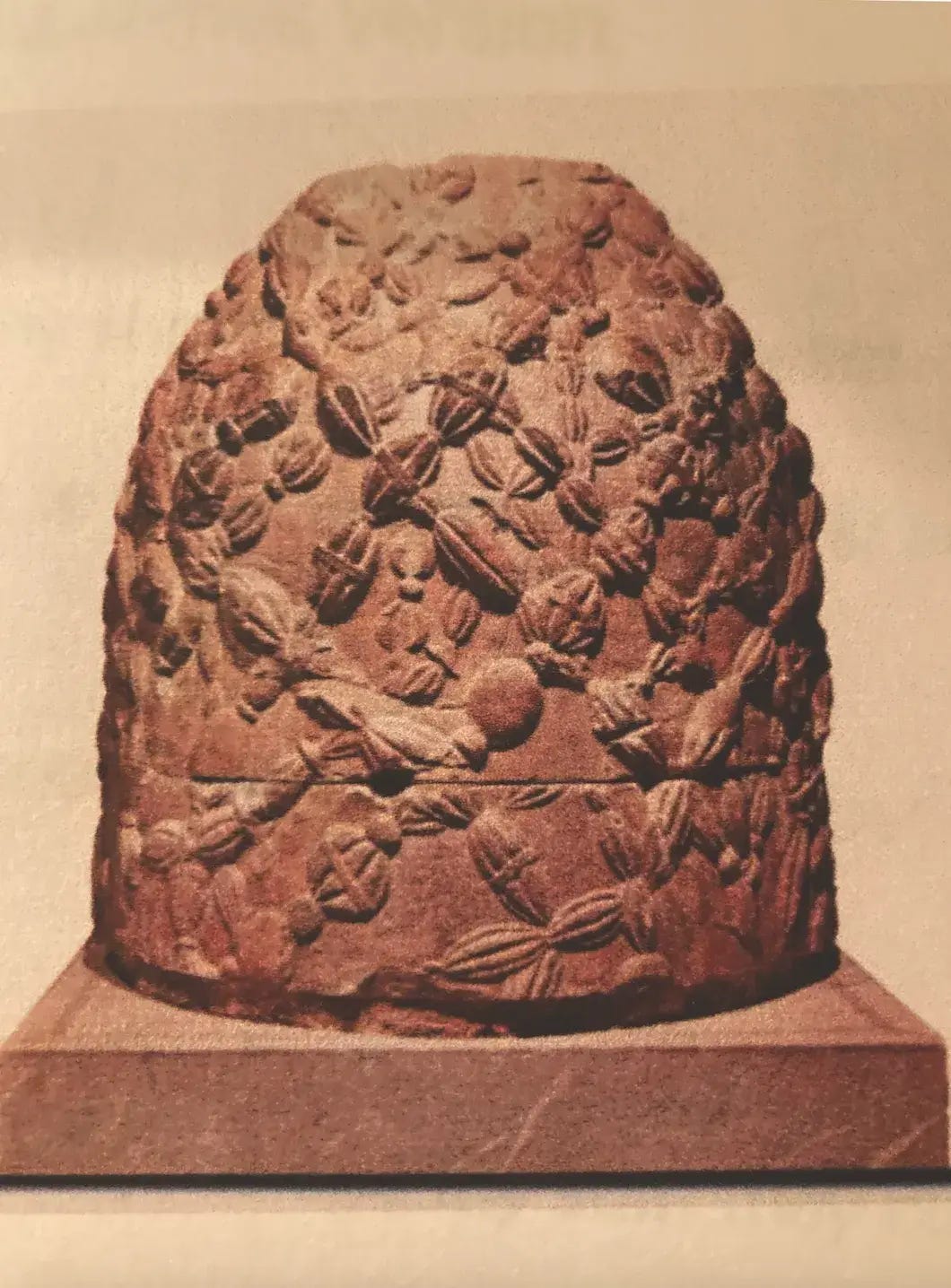

2 - The ancient Greeks believed that Zeus, in his attempt to locate the centre of the Earth, launched two eagles from the two ends of the world whose paths crossed above Delphi, which became the resting place for a stone artefact called omphalos, meaning the ‘naval’ of the world.

1 - If ancient mythology had some bonkers ideas, try asking a scientist. The centre of the universe for them? Nowhere. There isn’t one. With a universe that has been expanding since a ‘Big Bang’ about 14 thousand million years ago, we are to think of ourselves, says Arthur Eddington as early as 1933, as being like dots on the surface of an expanding balloon, growing ever farther apart from a centre long since forgotten.

The Examined Life

Schumacher aims to make a distinction between ‘know-how' and true education, but what are the implications for a society that blurs the lines between the two? How can we balance the need for practical, job-oriented 'know-how' with the need for a well-rounded moral and intellectual foundation? What, if anything, do we stand to lose if we can't?

If You Enjoyed It…

Go further by exploring this week's reading list:

Schumacher, E.F. (1973) Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered

Mastronarde, D. (1993) Introduction to Attic Greek

Rulfo, J. (1955) Pedro Paramo

Russon, M. (2022) The Life of Alfred Wallis

Or share with your people here:

Ok, that's it for this week! Thanks for reading. Next time, existential despair and pineapples.

Wonderful, fully agree that the humanities are important. Id argue they are even more important if we are a dot on an expanding balloon. The second law of thermodynamics is also aesthetically pleasing, but it may give less about the human condition that the arts.

I fully support the importance of the humanities and think they are often not taught very well (especially in pre-university institutions of learning).